A doorless brown van rolls slowly over the ground of an empty field, kicking up a cloud of dry dirt as it comes to a hault. I step in to see that all the rows of seats have been removed. Instead the whole interior is fitted with floor-to-ceiling brown and beige shag carpet.

“Welcome to the Shaggin’ Wagon!” the driver calls out.

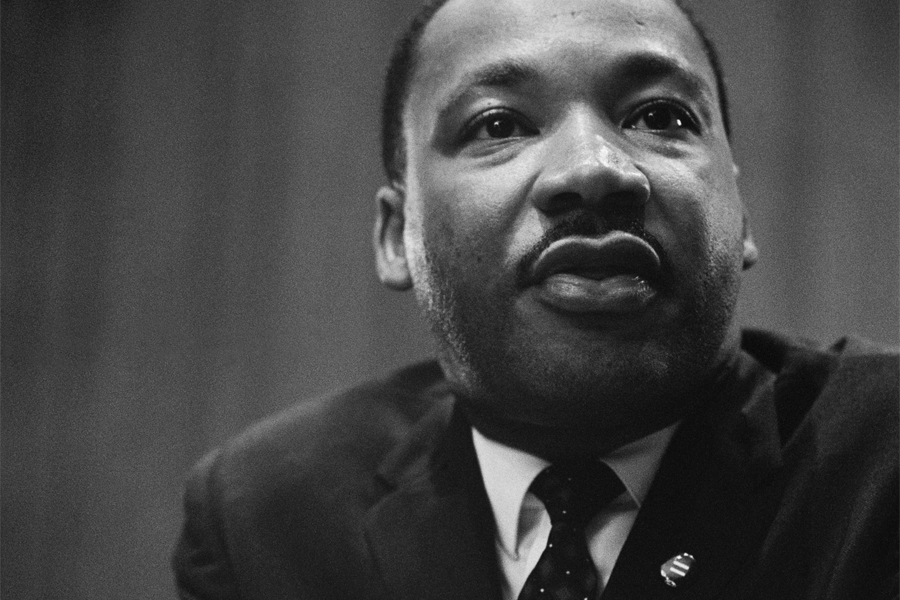

For my brother Mark’s 18th birthday I thought there would be no better gift as a send off to college than jumping out of a plane 13,500 feet above Earth. After all, if you could jump out of a plane, you can do anything. It seemed like a perfect metaphor for beginning a new, unknown chapter.

The Shaggin’ Wagon was our ride to glory.

But first there are a few things to take care of—like signing our lives away in front of witnesses, staring into the lens of a tiny video camera held by a really perky blonde-haired girl, and reading from a prepared statement.

“I understand that skydiving is a potentially dangerous activity that can result in injury or death. I, Jaclyn Gallucci, take final responsibility for my own safety.”

About 10 others wait for their turn and giggle nervously. It’s about 8 in the morning. I didn’t eat anything because I didn’t want to get sick after the stunt plane fiasco. In groups of two, names were called. It takes a lot of time to risk your life and there were about a dozen people ahead of us waiting for their turn. One hour passed. Two hours passed.

“Jaclyn and Mark?”

Now it was our turn. We step into the Shaggin’ Wagon and drive across the field, get strapped into our harnesses and assigned a tandem partner—the person who will be strapped to your back during the jump. Not that I had any thoughts of doing so, but you can’t jump out of a plane by yourself the first time. It takes training and dozens of tandem jumps to get an A-license, which allows you to jump on your own. It takes even more training to become an instructor.

As nice and sweet as it sounds, you also can’t jump through a cloud, without getting beaten to death by mother nature, I learned. But although a little hazy, the skies were generally clear and we were given the okay.

We climb in a small plane, just the four of us, attached in twos, and the pilot. The engine revs up and we get higher. And higher. And higher—the kind of high where everything starts looking like a map.

Mark is the first to jump.

“Are you ready to jump out of a plane, Mark?” I hear his instructor ask.

Why am I doing this to him? This is a stupid metaphor. Stupid! If we survive, my parents are going to kill me!

“Absolutely!” Mark answers and they jump right out.

I’m in shock. “Absolutely?!”

This was my idea and now I’m the nervous one?

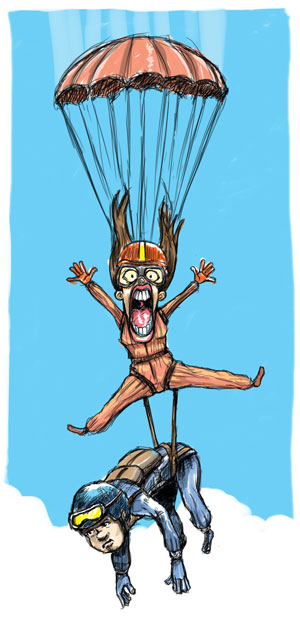

I watch with my legs dangling outside of the plane and the deafening sound of the wind up there. I see Mark’s bright red chute open below. I look at my feet over the world. Then out of the corner of my eye I see something that looks like a red deflated balloon twisted up and moving erratically, speeding toward the ground, getting smaller and smaller.

My heart stops and in that split second of panic all I could think was, “I just killed my brother.”

Before I could even process the thought, my skydiving partner points to the left and I see a big white chute floating peacefully toward the ground.

“They had to deploy the reserve chute,” he tells me. There must have been a problem, but don’t worry, that’s what the reserves are for!”

Not only do the instructors have a reserve, but every jumper has one, too, so even if one back-up fails, there is still another.

Later, watching the video, I saw the impressive MacGyver-like moves my brother’s instructor used to calmly deploy the back-up chute. While free-falling, this guy pulls out a pocket knife, cuts the failed chute off, holds the rip cord in his teeth, finagles something else and, as non-chalantly as if he just finished making a sandwich, a new chute appears like nothing. Wow.

If you were questioning why you need a license to jump on your own, ladies and gentlemen, here is your answer.

I inch closer to the edge of the plane, I’m halfway out. “Ready!?” my instructor yells out.

“Yep!”

We slide out. Free fall. I remember learning in physics that’s a speed of 9.8 m/s². It’s the feeling you get when you’re going downhill on the roller coaster and you get that chill in your stomach, except that feeling doesn’t go away. You just keep going down. Free fall lasts about 60 seconds.

I feel a tap on my shoulder. That’s my cue to get into starfish position, arms and legs out as we plunge toward earth. Beautiful. The sky that wasn’t blue on the ground was blue up here and I was flying through it. Then a sudden jerk from the pull of the rip cord.

We’re floating. I could stay up here forever. I’m not scared at all any more. I swung my feet up in front of me and saw them above the trees and houses again. The last time I did this I was in Disney World at Epcot, riding Soarin’, an aerial illusion trip in front of an 180-degree IMAX projection dome that makes you feel like you’re flying over some of the most beautiful places on Earth.

This time I really was.

My instructor tells me to give a thumbs-up to the tiny camera attached to his wrist as we float to the ground. As I get closer, I see my brother land gracefully on his feet, but more importantly, alive, in front of me. Now it’s my turn to stick the landing. The key is to keep your legs parallel to the ground and slowly lower them like a plane’s landing gear. I didn’t quite find that sweet spot, and I hit the ground in a blaze of glory like I was sliding into home in Game 7 of the World Series. My new metaphor? If you can jump out of a plane—and your chute fails—and you still make it out alive—you can do anything.