Most people today might associate Jackie Kennedy Onassis with Cape Cod or Rhode Island, or sadly, Dallas, but Long Island had a lasting influence over the course of her life, beginning with her birth in Southampton in 1929.

For one thing, it’s here she got her first brush with fame. Granted, she was only 2 years old. But as the East Hampton Star proclaimed, it was an auspicious beginning: “Future debutante hosts second birthday bash.”

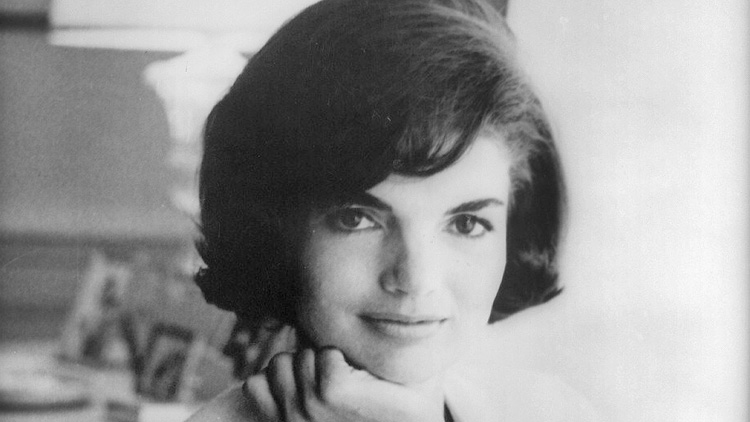

When she did “come out” in 1947, nationally syndicated gossip columnist Cholly Knickerbocker called her “the No. 1 deb of the year…a regal brunette who has classic features and the daintiness of Dresden porcelain.”

Beneath the surface was a different picture.

It was at her family’s and her grandparents’ East Hampton estates where she spent her most formative summers, developing her horse-riding skills, honing her lifelong love of literature and culture, and learning to depend on herself as her parents’ loveless marriage went up in flames.

By 1937 the marital bond of Janet Lee and John Vernou Bouvier III had come unglued but the divorce didn’t become official until 1940. Jackie’s presence on the East End began to wax and wane like the phases of the moon once her mother had married Hugh D. Auchincloss Jr. and moved her and her younger sister Lee to his family’s estate in Newport, R.I. Mother Janet associated Long Island with her despicable ex and the less time her daughters spent in the Hamptons, the better.

Jackie’s position in our country’s cultural pantheon has also fluctuated with the changing times. On that tragic November day in 1963, she was America’s widow. But later, as time had passed, she seemed to prefer the comfort of shadows, not the glare of the limelight.

It’s understandable, therefore, how four young guys from Huntington out for the weekend at their friend’s parents’ place in the Hamptons could keep their cool when they found themselves unexpectedly sharing the stage, so to speak, with the former First Lady in 1978. They had been walking back from the beach when a beat-up old Chrysler roared by.

“Look!” said one of them, who recognized the driver slouched over the wheel. “It’s Mick Jagger!”

Sure enough, this Rolling Stone was going to a Bastille Day party at George Plimpton’s summer home in Wainscott. It so happened that these fellows were staying right next door.

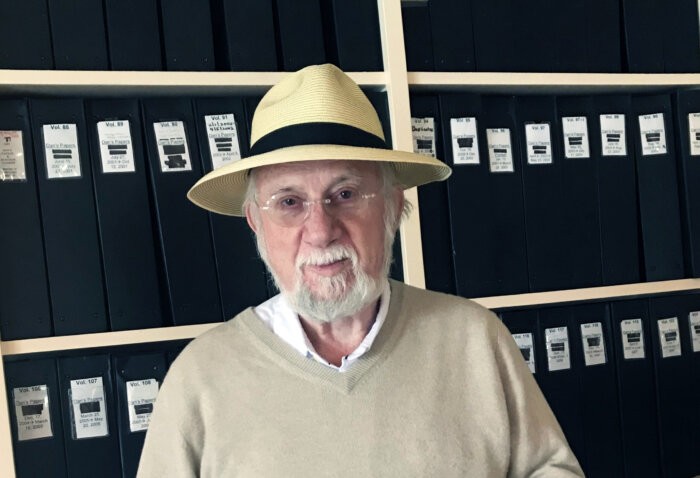

“We were invited because we were neighbors,” recalls their host, Scott O. Savitt, now a Long Island promoter. “It was hot, man!”

Among the celebrities assembled that night were Shirley MacLaine, Kurt Vonnegut, Dick Cavett, Buck Henry and Chevy Chase. But standing on the big sweeping lawn, gazing off into the distance, was once the most popular woman in America, if not the world.

“I look across the way and I see Jackie Kennedy!” recalls Bill Walsh, today a book marketer in New York. Later in the evening he spotted Norman Mailer thumb-wrestling with one of Bobby Kennedy’s boys, and, to top it off, Caroline Kennedy came up to him and asked him if he had a match.

“We ended up chatting about the weather,” he insists with a straight face. “The whole time I’m going to myself: ‘This is Caroline Kennedy and there’s Jackie!’ But I’m acting very blasé about the whole thing.”

As were his pals. But this foursome lost their composure the moment Jagger joined them on the lawn to share the joint they were smoking.

“As soon as Jagger walks away, my friend takes the joint and saves it,” Walsh recalls. “And he says, ‘I’ll never wash my hands again!’ For us, Jagger was really the star, and, ‘Oh, yeah, there’s Jackie Kennedy.’”

Perhaps Jackie O, as she would become dubbed in the supermarket tabloids, had become such a pop icon on the American scene that she could almost be taken for granted.

Two Jacks, One Jackie

But Jackie had as much right to be there as anyone, let alone a bunch of 20-year-old party crashers. Her Long Island roots went far back.

The Lees, Jackie’s mother’s family, owned Avery Place, on Lily Pond Lane in East Hampton.

That’s where Janet Lee perfected her horse-riding skills and passed them along to her daughter early on. Newspaper accounts of the time lavished praise on young Jackie’s equestrian accomplishments as she racked up one blue ribbon after another.

The Bouviers, on her father’s side, had bought a clapboard-and-shingle house called Wildmoor on Apaquogue Road in 1910 before acquiring the much more opulent Lasata estate in 1925 off Further Lane, its name supposedly meaning “place of peace” in Algonquin.

Indeed walking along the shore in the Hamptons had a lasting effect on her, as she wrote in a poem when she was 10 years old: “When I go down by the sandy shore,/I can think of nothing I want more/Than to live by the booming blue sea/As the seagulls flutter round about me.” It was a habit she maintained on Cape Cod once she became part of the Kennedy compound in Hyannisport, Mass.

She had met John F. Kennedy in 1951 when the Congressman was “three weeks shy of his thirty-fourth birthday” and she “was not yet twenty two,” writes Donald Spoto in his Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis: A Life. But she knew then that he “would have a profound, perhaps disturbing” effect on her and, she also admitted later, that “here was a man who did not want to marry.”

In that sense, Kennedy was not unlike her raconteur father, “Black Jack” Bouvier, who had gotten that sobriquet because he nourished his tan in the beaches of the Hamptons and in the solarium room at the Maidstone Club in East Hampton, where he stashed his liquor and squired his mistresses. He didn’t approve of his future son-in-law’s politics (Bouvier was a staunch Republican), but when they finally all met at a Manhattan restaurant in February 1953, both Jacks got along great, as Spoto writes, because the two men “shared the same passions for women, politics and sports.” Perhaps because Black Jack used to tell his daughter that “all men are rats,” Jackie was prepared in advance for her husband’s adultery.

After they’d been married 10 years, Kennedy himself told his friend Chiquita Astor, recounts Sarah Bradford in her book, America’s Queen, that he’d never been in love, “but I’ve been very interested once or twice.” But Jackie didn’t expect it from him, her biographers say. Though 12 years separated their ages, their similar backgrounds made them compatible, as Spoto put it, because “they had each endured a lonely and difficult childhood with emotionally distant mothers and philandering fathers.” And both found solace walking along the beach.

Fateful November

In October 1963, after losing her infant son Patrick, who was born prematurely in August and survived less than 40 hours, Jackie had decided to join her sister on a two-week luxury cruise in the Mediterranean with Greek tycoon Aristotle Onassis aboard his 303-foot-long yacht. Jackie said she found him “an alive and vital person who had come from nowhere.” (They would marry in 1968.)

At the time, his reputation in America was less gracious and more spurious, with his “dubious” dealings with European governments and American shipping companies creating the impression that he was something of a pirate, as Spoto writes. The trip helped fuel a backlash among Congressional Republicans that she’d gone too far.

So, feeling some remorse, she readily agreed to accompany her husband on his upcoming trip to Texas—her “first political appearance since 1960,” according to the author.

On Nov. 22, an open black Lincoln limousine took the First Lady and President Kennedy through the crowded streets of Dallas with Texas Gov. John Connally and his wife Nellie in the front seat and the Kennedys in the rear. Then the bullets struck. Jackie turned to look at her husband.

“I could see a piece of his skull and I remember it was flesh-colored,” she told the Warren Commission in 1964. “I remember thinking he just looked as if he had a slight headache.”

As the motorcade raced from the plaza to the hospital, she crawled onto the trunk of the limo to fetch the bone before a Secret Service agent shoved her back inside.

“They have killed my husband!” she screamed. “I have his brains in my hand!”

He was gone, dead at 46.

Yet Jackie endured.

And until her death in 1994, she lived as both a public figure and a private presence—a complex person whose seminal contribution to American culture and politics is still not fully appreciated, long after the refrains of “Camelot” have receded into silence, long after the tears shed by a grieving nation in 1963 have dried, and long after all the “celebrity sightings” over the years—whether by a hazy group of guys smoking pot in the Hamptons or a pack of paparazzi hounding her down Fifth Avenue—have faded from view.