Margaret MacMillan’s latest book on World War I, The War That Ended The Peace, opens with the Paris Universal Exposition in 1900. Countries from around the globe gathered in Paris to reveal inventions and works of art and to generally boast about nationhood. The event was underscored by political tensions but fueled by a collective optimism that technological advancements, many of which were on display at the exposition, would bring the world closer together and usher in lasting peace on Earth.

Margaret MacMillan’s latest book on World War I, The War That Ended The Peace, opens with the Paris Universal Exposition in 1900. Countries from around the globe gathered in Paris to reveal inventions and works of art and to generally boast about nationhood. The event was underscored by political tensions but fueled by a collective optimism that technological advancements, many of which were on display at the exposition, would bring the world closer together and usher in lasting peace on Earth.

Fourteen years later, the world order collapsed. The Great War engulfed the very nations who proclaimed the 20th century as a new and peaceful era. Within five bloody years, vast empires had crumbled, maps were redrawn and a generation of men was decimated.

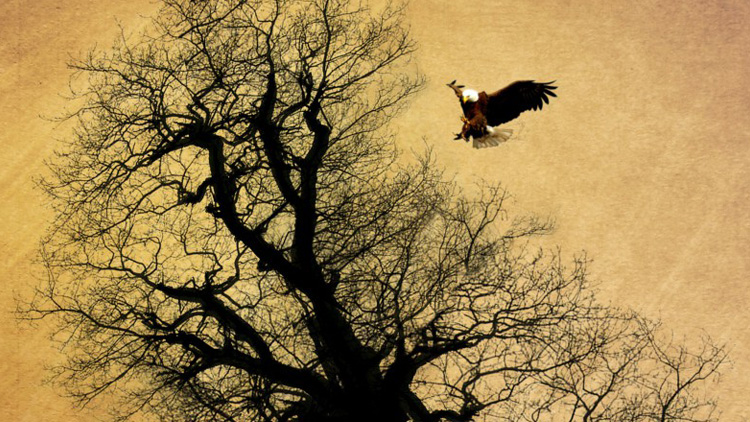

Great Britain entered World War I as one of the most impressive imperial empires the world had ever known; incredible given its size. Much of their greatness was attributed to being the greatest naval power in history. After the war, it was never the same. There are obvious parallels to be drawn between the position of the United States today and Great Britain’s a century ago. There are lessons to be heeded from their story.

Our disastrous wars in the Middle East at the beginning of the 21st century are akin to the Boer War fiasco Britain was embroiled in at the turn of the 20th century. The Boer War engendered near-universal antipathy toward the aging lion. Most notably, it drew strident criticism from the German people and Kaiser Wilhelm, which contributed to the burgeoning schism between the two nations.

One of the most striking similarities between the two eras is the manner in which Britain and the United States approached empire-building at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, respectively. Britain was suffering from growing pains related to over-colonization as its empire stretched around the globe. The U.S. is experiencing similar aches in its attempt to recover from naked imperialism under the guise of spreading democracy for the past 60 years.

Both nations display a paternalistic attitude toward “lesser” nations and believe a western style of governance was easily adopted through what Franklin Henry Giddings termed, “consent without consent.” In doing so both empires wore out their welcomes abroad and maintained relations strictly through fear of violent reprisal or loss of economic trade.

The British government was increasingly pouring resources into maintaining the largest navy in the world while ignoring the domestic cost of an aging population. Instead of cutting back on imperial pursuits and bolstering spending at home to stabilize its economy, it engaged in an arms race with Germany and sought new economic alliances in the event the two nations proceeded down the path to war.

Sound familiar?

The problem with military power is that it creates a desire among world leaders to employ it. Just as Capitalism requires constant growth, the suppression of labor and consumption of natural resources, the Military Industrial Complex requires conflict in order to sustain and justify its very existence. Despite famously being credited with the phrase, “Speak softly, and carry a big stick,” President Theodore Roosevelt sent America’s Great White Fleet around the globe to impress the world and privately lamented the fact that he did not preside over a war while serving in the Oval Office. His successors would put America’s newfound might to use, however, as the United States embarked on a century of unprecedented warfare and imperial harassment.

The dawn of the 20th century was rife with warmongering characters such as Roosevelt, who shared his attitude toward war. This idea is perfectly encapsulated in the words of Count Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf of Austria-Hungary: “The army is not a fire extinguisher, one cannot let it rust until the flames are coming out of the house. Instead it is an instrument to be used by goal-conscious, clever politicians as the ultimate defence of their interests.”

Naturally, the madness of these nations is somewhat clear. In hindsight, though, these are not the exclusive circumstances that led to the Great War. Nevertheless, one can’t help but experience déjà vu when examining the behavior of the Bush administration and the continuum that is the Obama administration. President Obama’s “pivot to Asia” is eerily similar to Britain’s thirst to tap into the faltering Chinese and Ottoman Empires of its age. Moreover, its effort to marginalize its perceived enemies through new and aggressive trade alliances is comparable to the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) currently being negotiated in secret between the U.S. and many of its so-called “client nations,” such as Canada, Japan, Mexico and South Korea.

The TPP is essentially an attempt by the U.S. to constrict China’s growth in the coming years by allowing TPP-participating nations access to labor forces in poverty-stricken parts of the world. It would function much like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), in that the subordinate nations would be subject to the economic and human rights abuses of the more dominant nations.

Those familiar with the neo-liberal treatise called the Project for a New American Century will rightly view the TPP as the next logical evolutionary step in the process toward maintaining U.S. hegemony in the world by any means necessary. Where military interventions have failed us, a new form of economic warfare is stepping up to take their place.

For its part, China is responding as one might imagine—with a show of force and steady shift toward economic policies that bear a closer resemblance to Capitalism, though this may never be fully recognized. President Xi Jinping’s 10-year plan is called “The Chinese Dream,” which obviously borrows from the American Dream in its scale and ambition. Implicit in the Chinese Dream, as in the American Dream, is economic growth and continued technological progress. Inevitably, this will lead China down a familiar path. Growth is addictive and when it is no longer possible to grow through economic policies and market forces, empires do what empires do best: expand and acquire. Evidence of this strategy already exists, as China was more than happy to procure oil and gas contracts from nations, such as Iraq, that U.S. corporations walked away from after a decade-long struggle to obtain by forcible means.

Yet despite provocations between China and the U.S., there is a presumption that war is impossible given the interconnectedness of the world economies.

In an op-ed titled “The Great War’s Ominous Echoes” in The New York Times, Margaret MacMillan ruminates on this very theme, saying, “It is tempting—and sobering—to compare today’s relationship between China and America to that between Germany and England a century ago. Lulling ourselves into a false sense of safety, we say that countries that have a McDonald’s will never fight each other.”

MacMillan is right. Recently, China quietly joined the military fray in a significant way by revealing its first naval aircraft carrier and announcing plans to launch its first domestically built, nuclear-powered carrier by 2020. This announcement, in addition to China establishing a no-fly zone in the East China Sea and issuing several warnings to the Japanese government about its plans to increase its military presence, follows directly on the heels of President Obama’s decision to send American vessels into the region in 2012.

The United States would be wise to tread lightly in the coming years and begin to look inward to cure what ails it instead of continuing on this ceaseless path of imperial madness. We must address the colonies of dispossessed Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck and stop thinking about colonizing cheap labor pools of distant nations. We need a better plan to take care of our aging population and must provide greater educational resources to equip our young people with the skills they will need to get by in this world. This is the role of government. No nation can be truly secure until its people are.

When spending on our massive surveillance state and “homeland security” is taken into account along with Pentagon spending, fully 30 percent of our nation’s budget is allocated toward the military. And yet we wrangle over subsidies for programs that assist at-risk populations and cut pensions of those returning from our ignominious missions abroad.

One hundred years ago this year, 65 million men were mobilized in the Great War. By 1919 more than half were casualties of the war, with 8.5 million killed. Few in the world saw conflict on this scale coming. It was considered almost impossible due to the economic relationships between world power, technological advancements and fear that empires might collapse as a result. For those who believe that our financial arrangement renders war impossible, or impractical at the least, I leave you with MacMillan’s admonition:

“Globalization can heighten rivalries and fears between countries that one might otherwise expect to be friends. On the eve of World War I, Britain, the world’s greatest naval power, and Germany, the world’s greatest land power, were each other’s largest trading partners.”