• Mandated Heroin-Prevention Website Inoperative Until Press Inquires

• Elected Officials Clueless About Non-Compliance

• Heroin Overdoses, Arrests Up on LI Despite Prevention Efforts

• Father of OD Victim Who Sparked Prevention Program Outraged At Lax Oversight

When 18-year-old Natalie Ciappa of Massapequa fatally overdosed on heroin at a Seaford house party in 2008, Nassau and Suffolk counties were so outraged that they passed laws in her name launching heroin-arrest tracking websites to raise awareness of the opiate abuse epidemic.

The talented singer, cheerleader and honor student who was about to graduate from Plainedge High School had become the poster child of the epidemic, galvanizing suburban Long Island as residents came to grips with the fact that the scourge of heroin was not just an urban problem. Her untimely death and the laws it sparked served as a clarion call.

Or so it seemed. Nassau officials hadn’t updated their version of the website in three years.

At anti-drug lectures, Nassau police and prosecutors tout Natalie’s Law, which also requires Nassau—but not Suffolk—police to notify school superintendents of heroin busts in their districts, alerting educators to when there’s an added need to teach students about the dangers of drug abuse. But, some of those presenters, even some legislators who voted for it, were unaware that Nassau disregarded half of a landmark local anti-heroin law it enacted following a Press investigative series in 2008 that exposed the depths of Long Island’s heroin epidemic. One could barely remember the law’s namesake.

“I can’t believe it’s six years ago that, um…oh my gosh, I know the name,” Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice said last month as she struggled for five seconds to remember Ciappa’s name during an anti-heroin presentation—a program named for what Ciappa’s parents heard from other unwitting parents at their daughters funeral, “Not My Child”—at a Syosset middle school.

To be fair, Rice’s office is not responsible for updating the so-called drug mapping index website—online maps that show where heroin arrests have occurred. The police and information technology departments are. But, Nassau Police Inspector Ken Lack, the department’s chief spokesman, dismissed a Press request for comment on the issue, stating that the agency’s entire website was under construction—although that was only since January. Brian Nevin, a spokesman for County Executive Ed Mangano, later blamed “technical issues” and said the heroin map site “will be back up shortly.”

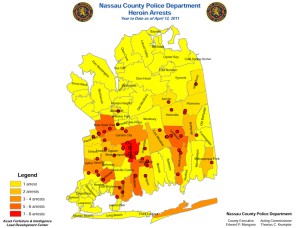

The website finally re-launched last week, two months after the Press asked why it was down, but without explanation for the three-year gap in compliance with the law. It only lists heroin arrests for the first three months of this year, with Massapequa still leading the county. Natalie’s father, Victor Ciappa, is livid.

“So, basically, they took my daughter’s name and her memory and passed a great law but nobody’s doing a fucking thing,” he says, adding that he suspects that schools aren’t taking action—such as alerting parents—when police notify administrators of nearby heroin arrests. “I am more frustrated than I ever have been in my life.”

Robert Freeman, executive director of the New York State Committee on Open Government, is confounded by Nassau’s failure to use its own law.

“It would seem that the idea is to raise consciousness and to serve as a deterrent,” he says. “And the purpose of the law is being defeated.”

The former Nassau legislator who authored the law—Suffolk quickly followed suit with their own website, although it’s neither comprehensive nor promoted—calls the failure “disturbing.”

“Given the fact that heroin is a problem across every demographic line and community, there needs to be more of an emphasis on using the tools that we have to help people,” says former Democratic Nassau Legis. David Mejias, who is now an attorney in private practice.

“How it fell through the cracks, I don’t know,” Presiding Officer Norma Gonsalves (R-East Meadow) said when she first learned from a Press reporter that the site had been abandoned.

“I think they kind of lost interest,” says former Democratic Suffolk Legis. Wayne Horsely, who authored his county’s version. “It didn’t get the play it should get…I think there’s room for expansion if they can get the graphics correct.”

Nearly 500 people have died of heroin overdoses on LI since Natalie’s Laws were passed, according to statistics provided by medical examiners in both counties. That’s nearly double the number of people murdered on the Island in the same time period.

Of course, a website alone could not have saved those lives, but Nassau’s disregarding it for so long indicates that drug prevention—a key part of a much-touted, three-pronged approach that also includes treatment and enforcement—sometimes amounts to little more than tough talk with little follow-through. It’s impossible to say how much crime was prevented by other anti-drug initiatives, but a nearly 30-percent increase in heroin arrests on LI over the past five years suggests that those efforts fell short despite the common refrain that police cannot arrest their way out of the crisis. Experts, law enforcement and former users confirm that the cyclical resurgence of heroin as LI’s drug of choice is partially attributable to crackdowns on the prescription drug black market that made painkillers pricier—resulting in a 44-percent increase in fatal heroin ODs on LI since ’09.

More than 4 million Americans ages 12 or older had used heroin at least once in their lives as of 2011, and the total increased by another 300,000 the following year, according to the latest figures available from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, with nearly a quarter of those getting hooked. And heroin is easier than ever to get, since U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration officials say Mexican and Colombian drug cartels have flooded the market, with the DEA making 20 percent of the heroin seizures nationwide in New York—including a trio allegedly busted in mid-April with $12 million in dope.

Dealers that describe the way buyers flock to them as “feeding the birdies” profit because the stigma from the previous heroin crisis in the 1970s is lost on teenagers. New users continue replacing those lost to overdose—or saved by recovery—especially since the new wave of heroin is more pure and snortable, although many wind up injecting the drug.

“You can’t experiment with it; it’s too powerful,” says James Hunt, acting special agent in charge of the DEA‘s New York Field Division. “The heroin that’s on the streets now is much stronger than it was 40 years ago, more potent and consequently more addictive.”

Jeffrey Reynolds, executive director of the Long Island Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (LICADD), wonders why LI appears to be losing its war on opiate abuse.

“It’s a question that I think more and more of us that work on this are asking: What’s broken?” he says. “Maybe the answer’s nothing, and it’s just [that] we’ve been overwhelmed by this problem. But something’s not working optimally.”

THE NEEDLE AND THE DAMAGE DONE

Taylor Sherman was popping Vicoden and snorting heroin a year after he began boozing and smoking pot at 14, self-medicating his depression as prescribed by the Commack High School “popular kids” who accepted him.

He graduated to shooting heroin intravenously at 17, upon learning that’s how his best friend fatally overdosed—a testament to an addict’s self-destructive logic. Escalation to snorting cocaine, smoking crack and using hallucinogenic drugs soon followed. So did arrests, psychiatric-ward stays and nearly a dozen aborted trips to drug rehab, as he seemed destined for jail or the morgue, same as countless users before him.

“It took me to my knees by the age of 20,” says Sherman, now 23, two years sober and training to become a substance abuse counselor after a spiritual awakening. “I needed the heroin and the drugs to give me a solution to how I felt…They took away the emotional, the mental pain that I suffered.”

He’s one of the lucky ones who lived to tell his cautionary tale with the hope of helping others avoid a more tragic fate.

Since Sherman first started to shoot up, heroin overdose deaths on LI rose 44 percent, from 85 in ‘09 to 122 last year. That’s a 74-percent spike from 47 to 82 ODs for the same time period in Suffolk, versus a slight rise from 38 to 40 in Nassau, according to county medical examiners. Nassau police said 21 people died of heroin ODs so far this year, half of last year’s rate in the first three months of ’14.

Non-heroin opiate fatalities in Suffolk dropped from 110 to 104 after peaking at 174 in ’11. Eighty-eight people overdosed from non-heroin opiates in Nassau last year, about the same as five years ago, after topping 100 in ’12, although a toxicologist in the county cautioned that adding all non-heroin opiate OD deaths together can be misleading because there is overlap in some cases in which a victim ingested more than one prescription drug. Officials also noted that the ’13 figures were preliminary while the latest cases were not yet completed.

The rising heroin overdose deaths and declining painkiller ODs have been credited to authorities cracking down on dubious doctors selling prescriptions after two LI pharmacy robbery shootings left six dead in 2011. It’s partly a side-effect of physicians checking their patients’ prescription history through a new database under New York State’s Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing Act, commonly known as I-STOP, which is credited with largely stopping doctor-shoppers—users who go clinic to clinic with fake symptoms, racking up pain pills.

But, once the pill free-for-all ended, those who had become dependent upon prescription painkillers—semi-synthetic opiates that offer similar highs as heroin, such as Vicodin, which contains hydrocodone, and oxycodone-based Percoset—saw prices as high as $1 per milligram. The choice for many users came down to $80 for an 80-milligram OxyContin pill or $10 for a deck of heroin. LICADD’s Reynolds says he sees kids with 10-to-15-bag-per-day habits nowadays.

“After the prescription pill craze, a lot of kids in the suburbs and in the cities who could no longer get prescription pills, or that [it] became more expensive for them, they went to the streets and got heroin, and they wound up heroin addicts,” says Hunt, the DEA agent. “None of these kids thought they’d wind up heroin addicts.”

In January, the Nassau medical examiner’s office took the unusual step of issuing a public alert to warn users that heroin packets marked “24K” in red ink were linked to a string of fatal ODs. That brand, as such stamps refer to, was cut with fentanyl, a painkiller toxicologists describe as about 100 times more potent than morphine, and metamizole, a banned painkiller and fever-reducing drug.

Sherman—who notes it’s common knowledge among users that the whiter the heroin, the more fentanyl it’s cut with—says that despite the good intentions authorities had in issuing that alert, it likely had the opposite effect and fueled sales of that brand of heroin.

“The way the addict looks at is: ‘This stuff must be good if it’s killing people! Where can I get that?’”

COLD TURKEY

Shanna Lintz was strung-out and living in a rented Hyundai Sonata with her boyfriend when the couple ran out of money and decided to snatch a woman’s purse in Levittown so they could buy heroin.

Police quickly apprehended the duo after the fall 2010 robbery, but her 31-year-old boyfriend, Gasparino Godino, hanged himself in his Nassau jail cell. Having hit rock bottom, hard, Lintz later completed a nine-month inpatient rehab program—same as many before her, 28 days weren’t enough. Now, like Sherman, she’s in college training to be a drug treatment counselor.

“This is not something that I would ever have done if I wasn’t addicted to heroin and so sick that I just didn’t know how else to get what I needed,” Lintz told lawmakers through tears at a Brentwood public hearing in early April while recalling her arrest. “I was sitting in jail with $120,000 bail, my boyfriend was now dead and I just didn’t know what to do.”

Her case is just one of the heroin-related crimes—robberies, burglaries, car break-ins—that persist while Nassau and Suffolk county leaders frequently cite statistics that indicate crime is down. Such stats don’t refer to the rising number of heroin arrests.

“Last year was a big year for bank robberies…I attribute that mostly to the heroin,” Nassau Police Chief of Department Steven Skrynecki said at a recent East Meadow community meeting, referring to 29 such cases reported last year while recalling a high of 52 in ‘92. “Most bank robbers are either drug addicts, alcoholics or gamblers.”

LICADD’s Reynolds says: “Every time I see news of a string of robberies…I say, ‘That has heroin written all over it.’ And almost every time I’m right!”

OD stats may show a switch from pills to heroin, but arrests for possession of both types of drugs are up. Heroin arrests in Nassau rose 28 percent from 391 in ‘09 to 500 last year while prescription drug arrests rose 132 percent from 253 to 587 during the same time period, while Suffolk saw heroin busts increase 35 percent from 1,026 to 1,386. Suffolk could not provide stats for its prescription drug arrests. The DEA reports a 427-percent increase in heroin arrests on LI from 11 in ’08 to 58 last year.

After authorities nabbed top Mexican drug cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera in February, those looking to fill the void left by his arrest are widely expected to continue waging the inter-cartel Mexican Drug War for control of smuggling routes that has claimed 40,000 to 60,000 lives since ’06—with reported estimates that the death toll could be twice that. A similar rush to fill the vacuum is to be expected whenever LI’s dealers are rounded up, since the demand remains.

Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota, who dubbed the Long Island Expressway “Heroin Highway” because dealers use it to get the drug from the city to LI, so far this year busted a ring dealing Hollywood-brand heroin in the Hamptons and a couple supplying dealers with High Octane-labeled heroin from their Holtsville home—one of the county’s biggest busts in years. A West Islip school bus driver and a Merrick postal worker are among the latest arrested for alleged dope dealing. Spota and his counterparts in the police and corrections departments echo the sentiment that LI can’t arrest its way out of the crisis.

“Enforcement and treatment only come into play when education has failed,” says Suffolk County Police Deputy Chief Kevin Fallon, the department’s chief spokesman. “I say this even though I’m in the world of law enforcement.”

Suffolk Sheriff Vincent DeMarco, the lone-elected county official who’s a registered Conservative, told the same panel as Lintz, the recovering addict, that lawmakers need to increase access to rehab programs and break the cycle of addiction and recidivism, thereby saving taxpayer money—up to $250 daily per inmate at his jail.

“Because there is so much overlap between the criminal justice and drug treatment systems, I think there needs to be a concerted effort among policymakers to develop alternatives to incarceration that will address the underlying causes of addiction and crime,” he said. The judicial diversion program that allows judges to order non-violent offenders into rehab instead of jail is a start, but he’s urging leaders to add more.

Philip Seymour Hoffman’s fatal heroin overdose in Manhattan this winter was another reminder that even celebrities who can afford drug rehabilitation may avoid seeking help, with tragic consequences.

With the resulting renewed attention on the issue, state lawmakers launched a heroin and opiate task force to study proposals that would, among other things, make rehab more accessible for those who can’t afford it out of pocket. Another group of state lawmakers soon thereafter launched a heroin task force specifically for the East End. Congressional representatives proposed DrugStat, a drug-crime-data-sharing tool designed to increase coordination between law enforcement. And Suffolk legislators recently launched a task force on the issue—their second since ’10.

“Almost every elected official keeps asking me every time I see them: ‘Is it getting better?’” says Reynolds. “And I keep saying: ‘Well, no it’s not.’ And they’ve said: ‘Well, how come?’ And I say: ‘The same thing I tell my clients I’m gonna tell you guys: If nothing changes, nothing changes.’ And in reality, not much has changed in Suffolk County, or in Nassau County, for that matter. If anything, in some key areas we’ve gone backward.”

He points to prohibitive new rules requiring appointments five days in advance for detox at Nassau University Medical Center as opposed to on-demand treatment for addicts in withdrawal. Then there’s the Sandy-forced closure of Long Beach Medical Center, which left that hospital’s detox beds unavailable. And the few choices in alternatives to detox, which isn’t always medically necessary—being dope sick is painful, but not deadly, like withdrawal from alcohol or benzodiazepines such as Xanax.

On the plus side, St. Charles Hospital is opening a five-bed adolescent detox unit to go with an adult unit, Suffolk officials say.

In a year when Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin devoted his entire State of the State address to the heroin epidemic there, Nassau Executive Mangano and Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone last month spoke for about 10 minutes combined on the issue in their state-of-the-county addresses, mostly plugging their use of Narcan, an antidote for opiate ODs that is becoming more widely available. Bellone also announced a new anti-drug public service announcement the next day. Reynolds wonders if any follow-up would have been done to ensure that those saved by Narcan are referred to rehab, had LICADD not volunteered.

It’s not all bad news on the heroin trail, as eight agencies on LI have applied for new state grants expanding Narcan from Suffolk to Nassau police, and adding it to regular public training classes that teach families how to save loved ones before first responders arrive. I-STOP was also a big win, as was the Good Samaritan Law granting immunity from drug arrests to witnesses who call 911 to report ODs.

Now there’s momentum for a state bill that would mandate insurance companies pay for however many days of drug rehab a physician orders—a proposal lobbied against by insurance companies that, patients say, cut them off from rehab too soon, forcing relapses, often until arrest or a criminal court judge orders them into treatment through the diversion program.

Such ideas were debated earlier this month before the Joint Senate Task Force on Heroin and Opioid Addiction, which held a more than four-hour hearing on LI the week before, the first of a dozen statewide. The chair, State Sen. Phil Boyle (R-Bay Shore), proposed upgrading possession of 50 bags or more of heroin to a felony from a misdemeanor in an attempt to more harshly punish dealers. Hoffman reportedly had 65 bags on him when he died.

One participant reminded the panel that LI can’t legislate its way out of the crisis, either. Especially when the committee has to issue its report by June 1, allowing only two and a half weeks before the end of the legislative session to try and pass its recommendations. But worthy potential proposals abounded.

Some of the ideas discussed at the hearing include establishing a recovery high school to decrease relapse rates, requiring the state Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services to license largely unregulated “sober homes,” relaxing rules that require small mental-health facility patients from having to be sober six months to better address the underlying causes of abuse, and joining the dozen other states that legalized involuntary treatment so parents of teens over 18 can have a civil court judge order their kids into rehab.

Nassau Police Det. Pam Stark says she’s trained administrators in most of the county’s 56 school districts to use the Too Good for Drugs curriculum that features kindergarten-through-12th-grade lesson plans designed to reduce risk factors related to cigarettes, alcohol and drug abuse—as opposed to the Police Smart program in Suffolk. She’s looking to train the holdouts and parochial schools next. Still, even state Sen. John Flanagan (R-Smithtown), chair of the education committee, says too many LI schools “have their heads in the sand.”

Beyond the panel, lawmakers and advocates have also been lobbying the Department of Health and Human Services to overturn the Food and Drug Administration’s recent decision to approve for sale a new painkiller, Zohydro Extended Release, described as “heroin in a pill.”

“This country cannot ignore the powerful lessons learned from the massive and unparalleled increase in prescription and illicit drug abuse resulting from ‘crushable’ OxyContin and other prescription opioids—but this approval of Zohydro ER by the FDA does exactly that,” Attorney General Eric Schneiderman said.

Arthur Flescher, director of Suffolk health department’s community mental hygiene services, told the county legislature in February that there have been “preliminary discussions” with Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) in setting up a recovery school on LI, which would go beyond bringing treatment programs to William Floyd High School (WFHS)—a first on the Island.

“A true recovery school would communicate those values throughout every moment of the day,” Flescher said, referring to WFHS having a drug treatment program within a school where those in recovery are in class alongside users. “They really need that ongoing support, not to mention the life skills that other recovering peers can offer.”

Some experts beyond our borders insist upon thinking outside the box, including Dr. Peter Ferentzy, star of a documentary called The Adventures of Dr. Crackhead—hailing from the same city home as Toronto’s Crackhead Mayor Rob Ford—who suggests legalizing drugs to regulate them because, he argues, abstinence-only drug rehab sets those in recovery up for failure.

“The war on drugs is a bust,” he says. “We really need to see this more as a medical issue, as a public-health issue, rather than a criminal issue.”

Victor Ciappa, Natalie’s father, would rather see LI actually use the laws passed in his daughter’s name. That and teachers actively using anti-drug curricula, many more seats filled at after-school anti-drug lectures, the number of community groups taking up the cause continue to rise, additional “pill take-backs”—events offering the public a chance to empty their medicine cabinets of unwanted pills before they’re stolen by users—and no-dope public service announcements flooding the airwaves. And the overdose deaths to drop.

“I know there’s a lot of issues that people have to think about…but these are kids’ lives,” he says. “Heroin education needs to be pounded into these kids. It’s as bad as it’s ever been.”