To say it’s never been seen before is an over statement, but to describe the inspired new exhibition at the Nassau County Museum of Art as unprecedented in its 25-year history might be right on the mark. Certainly, the works in the museum’s collections have never been shown like this before—and that makes it a noteworthy aesthetic accomplishment.

In celebration of its 25th anniversary, the museum’s staff have delved deep to put this impressive display together, calling the fruits of their labors, “Out of the Vault: 25 Years of Collecting.” The show had its official unveiling March 20th, during what is hoped will be the last spring snow storm in 2015, but it will last well into summer, ending on July 12.

The exhibit draws upon the museum’s permanent collection, highlighting the patrons’ gifts to the museum over the last quarter century, many of which have never, or rarely, been put on public display before.

“We tried to pull out both new things as well as some things that have been in the collection for a while but haven’t been shown in a long time,” explained Karl Willers, the museum’s director. The museum owns about 550 works, he added, and he expects to have between 250 and 275 of them on display for this new show.

“It’s actually been a lot of fun putting it together,” said Fernanda Bennett, the museum’s deputy director. “We’ve kind of pulled everything up, got to look at it all, and then edited it out, in terms of what related, what had a nice rapport, and what felt good.”

There’s portraiture—past and present—plus an array of American landscapes, paintings and objects by Louis Comfort Tiffany, vintage Americana posters, works by Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Helen Frankenthaler, Larry Rivers, James Rosenquist and Robert Indiana. There’s also a provocative portfolio by the photographer Larry Fink, whose black and white work contrasts socialites in Manhattan with hard-scrabble families of rural Pennsylvania’s coal country.

The great American naturalist John James Audubon, known for his bird paintings, is represented here by the hoary marmot, the jerboa mouse, and the marsh shrew, among other notable rodents. It’s a nice, educational tie-in for children, considering that the museum’s surrounding property is officially the William Cullen Bryant Preserve, although these figures in the “quadrupeds” gallery, as it’s called during the “Out of the Vault” show, haven’t been spotted on the grounds themselves.

The overwhelming amount of art work encompassed by the exhibit may be vast but the multifaceted presentation feels right, not unlike the masterful arrangement of different genres of art assembled by the keen aesthetic of the Barnes Foundation’s museum in Philadelphia, whose brilliant collector, Albert C. Barnes, wanted to educate the average viewer’s eye “to see as the artist sees,” as he put it in 1925.

No less ambitious, this exhibit at the Nassau County Museum of Art promises to delight visitors whose tastes and styles vary widely. They will come away with their vision renewed, guaranteed.

Take the Tiffany room, right next to the pop art in gallery one on the first floor. “We have one of the largest collections of paintings by Louis Comfort Tiffany,” said Willers, as he gave this reporter from the Press a preview tour as the staff scrambled to hang the show before the next day’s opening.

From all around, there was the sound of hammers, staple guns, tape measures and excited chatter. At one point, Willers took special care to move a priceless purple vase into its proper place in its exhibit case. On the walls some of the paintings supposedly had the original Tiffany gold frames; certainly their finely etched designs imparted an exquisite touch to the canvasses they contained.

The second floor of the museum offered some surprises. In a prominent spot in the American portraiture room was George DeForest Brush’s stark painting, “The Matinecock Indian Chief,” who was looking very formal in profile as he gripped his calumet, a long ornamented tobacco pipe used in ceremonies. Originally completed in 1928, this portrait had hung at the Bank of America branch in Locust Valley for many years until it closed. According to the museum’s publicist, Doris Meadows, the community convinced the bank to donate the piece so it could remain in Nassau.

Nearby was a compelling wall-hanging by Joseph Hirsch called “The Wedding,” which showed a very grotesque old man dancing with his very young bride, as a jaded group of jazz musicians serenaded the newly-weds. The large painting exuded an air of social criticism in a style from the 1930s like that of George Grosz. Hirsch, it turns out, had gained national attention as a muralist for the Federal Works Progress Administration during the Depression. Later, Hirsch’s 1949 illustration for Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” showing Willy Loman stooped and defeated as he carried his suitcase loaded with products nobody was buying, became a world-famous poster for the play. This uncompromising work had no commercial potential.

On the other side of the gallery was Frederick Warren Freer’s compelling portrait of his new bride, “Lady in Black.” With her fashionably stylish black gloves, she holds a fan artfully spread to hide her décolletage. Painted in 1889, the portrait shows the influence of Freer’s studies in Europe, where he learned how to imitate the Dutch old masters’ use of browns, grays and blacks. Apparently, the painting was exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, where it won a medal. As the 19th century came to an end, Freer was one of America’s best known painters. He’s practically forgotten today.

In another gallery down the hall are photos of artists who are still quite well known. Taken by Berenice Abbott in 1948 is a gelatin silver print of Edward Hopper posing in front of a fireplace in his studio, looking like a banker in his conservative three-piece suit. Facing that work was a color photograph taken in the Hamptons by Linda McCartney of her husband, Paul, wearing a floppy hat but no socks, seated next to Willem de Kooning, stylish in his white painter’s pants, with one of de Kooning’s abstract expressionist works displayed behind them. The shot once adorned the cover of Art News in 1982 when the magazine ran a feature story on de Kooning’s celebrated career.

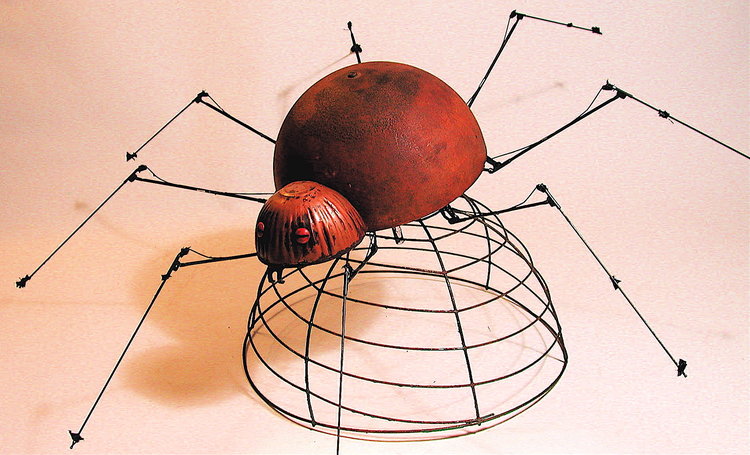

In a gallery around the corner is special selection of contemporary Long Island artists in the museum’s collection, called “Vernacular Visions.” It features paintings by Burt Young and Francisco Villagran of Port Washington and Susan Cushing of Southampton, and sculptures by Old Westbury’s Richard Gachot, who uses found objects the way artists use tubes of paint to make his whimsical creations.

A room devoted to “traditions in American landscape” was dominated by a very new acquisition, a stunning large color print called “Tree of Life,” taken in Oregon in 2010 by award-winning Australian photographer Peter Lik. On a glowing grassy knoll beside a pond stands a psychedelicized Japanese maple tree, its gnarled branches looking like the limbs of an old soothsayer silhouetted against a canopy of iridescent red leaves letting in sparkles of sunlight. Lik’s work has been featured at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and he starred in an NBC-produced TV series, “From the Edge with Peter Lik.”

For those who care about such things, “Phantom,” his black and white photo of a ghostlike image at Arizona’s Antelope Canyon, was acquired last year for $6.5 million, making it reportedly the most expensive photograph in history. To this reporter, “Tree of Life” is more vivid—and really worth gazing at for a very long time. Another hidden treasure brought to light because the Nassau County Museum of Art opened its vaults.

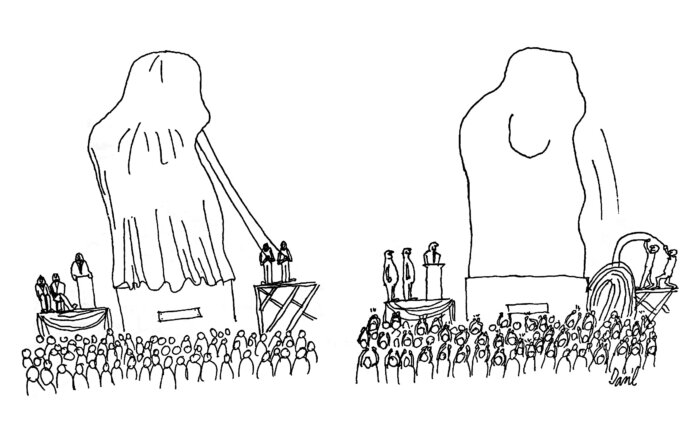

“We think audiences are going to like it,” said Willers with a justified mix of pride and delight, like a showman about to open the curtain to an eager audience ready to be dazzled.

“There’s a lot to see and it gives us a chance to show off for the first time some of the highlights of our collection,” he said. “I think it’s really one of the best looking shows that we’ve ever mounted.”

Nassau County Museum of Art is located at One Museum Drive in Roslyn Harbor, just off Northern Boulevard, Route 25A, two traffic lights west of Glen Cove Road. The museum is open Tuesday-Sunday, 11 a.m.-4:45 p.m. Admission is $10 for adults, $8 for seniors (62 and above) and $4 for students with ID and children aged 4 to 12.