Trying to encompass the far-reaching impact that Lee Koppelman has had on Long Island is no easy task.

The master planner has been active in civic, academic and planning circles for decades. From 1960 to 1988, Koppelman was the longtime director of the Suffolk County Planning Department. But longer than that tenure was his time at the helm of what eventually became the Long Island Regional Planning Board, which he served as executive director from 1965 to 2009.

A small look of some of his noteworthy accomplishments range from heading a pioneering study of the linkage between land use and water quality, promoting open space preservation across wide swaths of Suffolk, and playing an instrumental role in the creation of the Fire Island National Seashore.

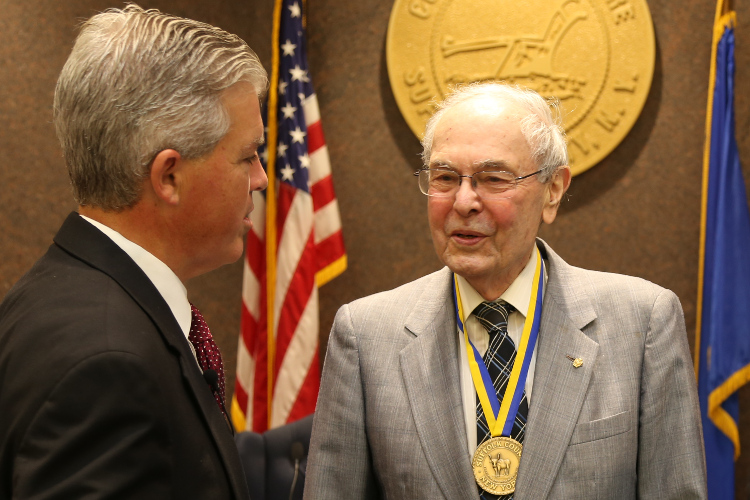

On Monday, Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone awarded the 88-year-old Koppelman the Suffolk Medal for Distinguished Service, the county’s highest honor, in recognition of his work. He drafted Suffolk’s first master plan in 1970 and was on hand at a public hearing in Hauppauge to share his thoughts on the county’s latest planning effort.

I first met Koppelman at SUNY Stony Brook University while I studying for my Masters in Public Policy. There, like so many other students before me, he taught the ins and outs of many topics including the fundamentals of urban and regional planning, land use, addressing Long Island’s housing, transportation needs and more.

Over the course of his career, Koppelman has seen many public officials and their administrations come and go, yet he and his team were able to steadfastly maintain his pragmatic approach to planning. According to him, maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism, and sticking to data-backed recommendations are the keys to success in his field.

So often people make plans, but few see them come to fruition as he has. In his own words, Koppelman says, “That’s why planners just have to be patient, and live long enough!”

Thanks to a healthy mix of professionalism, strong ethics, and the benefit of both foresight and decades’ worth of hindsight, his pointed thoughts carry as much weight now as they ever did. Koppelman is still as passionate about the issues facing us as he was during his early days in Suffolk government when he shared his desk with county executive H. Lee Dennison in a trailer in Hauppauge. What follows are edited excerpts of my recent discussion with LI’s veteran planner:

What is our greatest regional challenge?

We have several. I don’t even prioritize. Certainly, the basic objective of planning is to achieve balanced growth. That means you need all of the specific land uses to serve the human needs, and that includes the needs of the economy, as well as the environment. And that means you to have a balanced variety of housing, again consistent with the needs of the population at any point in time.

So if the population starts having more babies, you need more tot lots, you may need more elementary schools. If the population is aging, you need senior citizen activities; you need senior citizen housing. In other words, there has to be the full panoply of land uses to adequately meet the needs of the population at anytime that you’re doing the planning. So housing is a key priority.

We don’t have “affordable housing” for the young. That doesn’t mean there isn’t affordable housing, but for a young single person, the last thing they need to be saddled with is a house. We need studio apartments.

But any type of rental has been violently avoided. We did a whole series of studies on the tax consequence of different housing types. The single-family detached house has the heaviest tax burden. In contrast, rental housing (including two-bedroom units) are primarily used by either single people, or a married couple without children. The end result is that the taxes these rental units or condominium units or whatever they may be provide is a tax surplus. And the economics are very simple to understand.

As you continue to expand, the curve drops. In other words, the people who are buying the McMansions, proportionate wise, are paying less taxes than the average middle class family. And so if you look at the real estate taxes in any of the luxury communities, or especially in the Hamptons, all of the Hamptons, the houses there that are selling for $15 million dollars, their taxes may be $50,000 to $70,000. If you have a house in Stony Brook that’s worth a million dollars, you’re paying 50 percent that amount in taxes.

That’s why taxes are a crisis. And I can’t convince the people that it’s in their interest. We don’t have to put multifamily housing right on top of single-family, but they oppose it even if it’s half a mile away.

What is an easy first step to solving this challenge?

The status of the economy is one factor that has caused a turnabout, because now all the politicians are all of a sudden all concerned with jobs, and tax base.

The other is demographic. What has happened is that the very same people who were in their 30s and 40s, and opposed every single effort that I made to get rental housing available for the singles, the elderly, for the middle class who don’t need a house, whatever it is, and now 20 years later, the 30-year-olds are 50, the kids are out of the house, and now, all of a sudden, a condominium sounds like a great idea. In those days, even senior citizen housing was violently opposed.

The second prime problem is transportation, and here it’s affected by NIMBYism. Every time there’s opposition, the limited amount of highway funds is dissipated.

Now, in addition to that, you have a secondary problem. We don’t get 90 percent money on the interstate because once you get past Queens, it’s not continuous. And the interstate has to be continuous; it can’t be a dead end. So, the west end got 90 percent money, and everything in Nassau and Suffolk only got 50 percent funded.

Now, when I did the regional plan that was published in 1970, just to meet the transportation needs at that time was $17 billion. That was rail, and road. In today’s dollars, you can multiply that by 10 or 15. So right at the present, in my judgment, we need two referenda: an “open space” bond issue, and a transportation bond issue. I think the last transportation bond issue was when Rockefeller was governor in the ’70s.

The last point on transportation, since they [governments] are always short of money, they have more projects then they can pay for. If they propose a project, they’re not stupid – they know there is a need. Like Jericho Turnpike, the most fatal, accident-prone stretch of highway in the State of New York. Well, anytime anyone opposes anything that the Department of Transportation wants to do, the DOT pack up their maps, they take the money, and they go upstate. So we’ve been shooting ourselves in the foot every time we oppose something.

It was the same thing with the railroad. I did the plan for the railroad, called Park and Ride. We need double tracking on the North Shore/Port Jefferson Line. To do what the railroad needs requires certain accommodation. Everywhere from Route 110 in Huntington into Smithtown, whatever they [LIRR] proposed, the local people objected. So nothing can be done, and that’s part of the problem.

What has been the biggest change that you’ve seen on Long Island during the course of your career?

From a standpoint of the environment, we’ve made great strides. For example, in Suffolk County, more than 25 percent of the total real estate is in dedicated park lands. On top of it, the environmental studies that we initiated on the hydrogeology, the marine environment, on the Peconic estuary bay system, all of that has produced some good science, all emanating from the planning department. That’s been a success story, and that’s probably the greatest achievement we’ve made.

Our efforts at housing, until recently, have been largely a failure. We’re beginning to get senior citizen housing, condominium projects, nursing homes, independent living, so we’re beginning to get an array of housing choices.

On transportation, it’s been a mixed bag. A lot of my transportation plans now exist. The bus system exists. The electrification of the mainline of the railroad exists. I didn’t get the North Shore line because the MTA didn’t have the money. Otherwise, I would’ve gotten both.

What do you think Long Island will be like in 20 years?

It will probably look pretty similar to what we have now…with the exception that I anticipate a lot more urbanization that’s already taken place in Nassau County. The same thing that’s happening in Nassau County, that has happened in Queens. Queens, primarily, has been a low-rise community. A lot of single-family housing, apartment houses limited to four stories; you go higher, you need elevators, that’s what did it. But now that Manhattan prices have a median of about a million dollars per unit, and they’re socked in on Manhattan Island, the developers all of a sudden are discovering Queens.

From a standpoint of geomorphology, Long Island can sustain any type of building that you want to put up. Just look at Stony Brook University Hospital: five stories underground, 17-story building. So it can be done. In Nassau County, it’s already happening. In fact, if you look at the Hempstead Hub, which has about one third of all the economic activity on six or seven square miles, you’re surrounded by high-rise office buildings, or Hofstra University, with 17-story dormitories.

So, in the next 20 years, the builders are discovering that in Manhattan, where you have to buy the developable land by the square foot, if you’re smart, you buy on Long Island. Buy it now while it’s still cheap, with the idea within the next 10 or 20 years, they’ll build.

Rich Murdocco writes about Long Island’s land use and real estate development issues. He received his Master’s in Public Policy at Stony Brook University, where he studied regional planning under Dr. Lee Koppelman, Long Island’s veteran master planner. Murdocco is a regular contributor to the Long Island Press. More of his views can be found on www.TheFoggiestIdea.org or follow him on Twitter @TheFoggiestIdea.