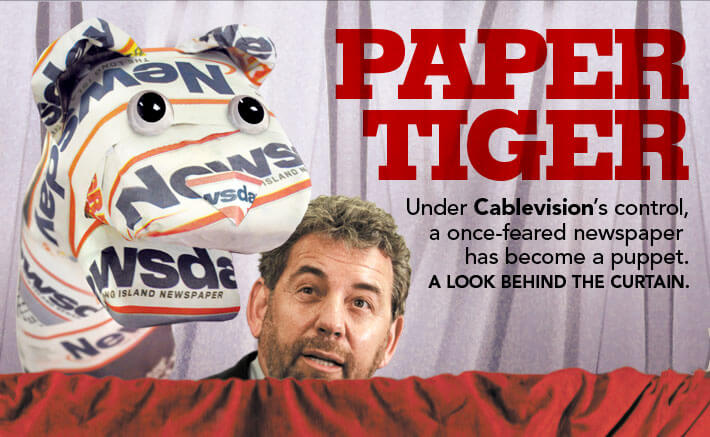

It’s clear that Newsday is not what it was, but then, neither is the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Washington Post. At one point, Newsday was considered in the top 10 of great American papers, but it hasn’t won a Pulitzer Prize, the industry’s most prestigious award, in five years —and the Knicks look more likely to win an NBA playoff round long before Newsday garners its next Pulitzer.

That wasn’t the case in the heady days of the 1990s when both the Long Island paper and its city upstart, New York Newsday, were raking them in. One of those prize winners was Bob Keeler, who received the 1996 prize for beat reporting in his series portraying the inner workings of a Catholic parish on LI. An editorial writer today, Keeler is removed from the inner workings of the newsroom, but he cautions that any reporter-editor friction is not exactly the story of the decade.

“Newsday is an editor-driven paper—always has been, always will be,” says Keeler. “I’ve written about it, in my worst-selling book on the history of Newsday, and I’ve lived it. In the early 1990s, a bunch of us reporters gathered together and formed a reporters’ committee, because editors were being particularly high-handed. Despite the historic difficulties of organizing journalists, we did manage to meet a few times, and we put out a few issues of a newsletter. For a time, the editors became a bit more collegial and a tad less high-handed. But that was just a phase. Over-the-top editing is a lot like kudzu: You can beat it back, but it always returns.”

Howard Schneider, former Newsday editor in chief and now dean of Stony Brook University’s School of Journalism, takes the long view.

“Every newspaper in America will go through their hyper-local phase and, like adolescence, somehow they’ll grow into another level of maturity,” he says. The problem is not finding an audience but establishing a viable business model in “this post-multi-media world,” and enterprising journalism can determine who survives.

“I think the great differentiator for news organizations and individual reporters,” Schneider says, “will be the ability to find stories that nobody else finds, the ability to get to the bottom of stories that nobody else can get to the bottom of, and the ability to respond to misinformation with authoritative information quickly.”

The question is whether Newsday is still capable of doing that kind of journalism, some critics say, or even aspires to.

“We’re still the only daily,” says a Newsday staffer. “I think we’re still relevant. But the paper backs away from difficult stories and everything’s written in the same voice because of the heavy-handed top-down editing, and we bow and scrape to certain elected public officials. I do believe our credibility is not what it once was.”

Journalists from outside LI looking in also expressed concern.

“When you give up covering the news in favor of community building, I think you’ve basically reprogrammed the thought process of the newspaper and made it a lot less hard-driving, and a lot less interesting,” says Curt Hazlett, a former managing editor of the Portland Press Herald in Maine, night city editor of the Washington Post, and “journalism trainer” at the now defunct American Press Institute.

“It’s hard to be an editor,” says Hazlett. “You’re responsible for things that are inherently controversial. And if you’re any good, you’re putting things in the paper that a lot of people don’t want to see published—but publicizing something that someone somewhere doesn’t want to see is exactly what the definition of news is.

“It’s a lousy time to be a journalist,” he observes. “There’s plenty of pressures against newspapers as it is, but lack of news is what drives the final nail in the coffin.”