Part one of this article in last week’s issue of the Observer detailed Colonel James Fitzmaurice’s 1928 east to west flight across the Atlantic with Hermann Kohl and Baron Gunther Von Huenfeld. After the flight, the two Germans returned to their homeland, while Fitzmaurice remained in the New York area. He had met three Irish real estate agents who were interested in using his name to promote a new housing development they planned to build on Long Island. Their names were Michael Brady, Frank Cryan and Peter Colleran and their development became the Village of Massapequa Park.

Brady, Cryan and Colleran (BCC) had started their company in 1927, aiming to capitalize on the growing interest New York City residents were showing about moving to Long Island. The Queens Land and Title Company had started to develop the area west of the Massapequa Preserve in the early 1900s, but World War I had slowed their efforts.

BCC became interested in the eastern part of the Massapequas after they learned that Robert Moses was considering a road that would lead from his soon to open Southern State Parkway to his soon to open Jones Beach. Governor Alfred Smith, a fellow Irishman, had heard the road would run through the Massapequas and informed BCC. Accordingly, they formed their company, bought large tracts of land north and south of the Long Island Rail Road east of the preserve and hired 40 real estate salesmen. They advertised throughout Irish neighborhoods in New York City, enticing customers with inexpensive land and houses, open spaces and easy access to New York City. Their sales pitch included free train rides to the Massapequa station, from which prospective buyers were bused to sites and given corned beef and cabbage dinners after deals were concluded. In fact, their office on Sunrise Highway and Park Boulevard was commonly known as the “corned beef and cabbage building.”

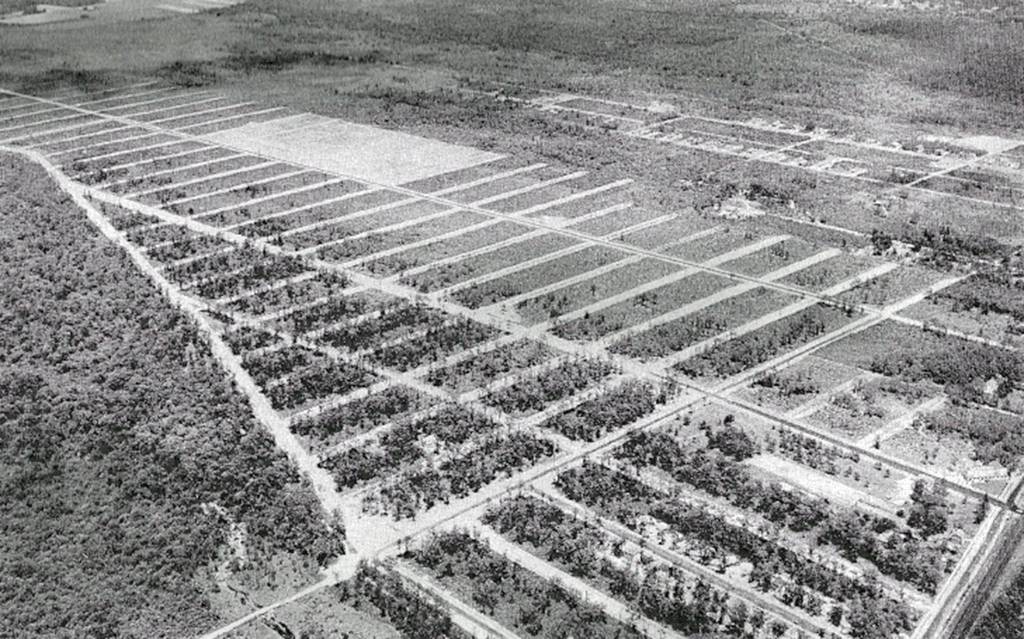

Their most unique enticement was an airfield, laid out in what became Massapequa Park north of the railroad, which would allow residents to fly their planes to and from New York City, or wherever they worked, and to keep them there for recreational use. BCC exploited the Irish connection by convincing Fitzmaurice to lend his name to the field. The result was a small field with two runways, the larger 1,800 feet long, extending from Roosevelt Avenue east to Second Avenue and from Spruce Street on the north to Smith Street on the south. The field opened in May 1929 to great fanfare, with a crowd estimated at 50,000, including many well-known aviators. BCC also started an Irish Aero Club, using Fitzmaurice as its president to enhance interest in the Flying Field. Fittingly, Tom Murphy was hired to run the field and passed it on to his son, also Tom, establishing another Irish connection.

Initially successful, BCC’s success began to unravel as the firm kept payments made by customers, but delayed building homes and reneged on running water pipes or power lines to the sites that were bought. Several buyers alleged their contracts were written in such a way that BCC could void them on flimsy pretexts and could keep their money. After several lawsuits, their real estate license was revoked in October 1932. Several years later, they sold the field to Nassau County for nonpayment of taxes.

The legal issues involving BCC as well as the Great Depression curtailed whatever development was envisioned in the 1920s and directly affected Fitzmaurice Flying Field. Several homeowners kept their planes there, but the surrounding area never developed to the point that it became a busy airfield. Hangars were built at the north end and the planes kept there were used as trainers for young pilots. Tom Murphy, Jr. became a licensed instructor and taught youngsters the basics of aviation. Flying was restricted during World War II, as fuel and parts became diverted to the war effort. Sometime during the war, Ken Tyler, a Hollywood stunt pilot, bought the field and operated Tyler Flying Services. He sold it in 1947 to Tom Murphy Jr., who ran the Skywriting Corporation of America, taking advantage of the captive audiences at nearby Jones Beach.

Ironically, the large population that BCC thought would be attracted by the Flying Field led to its demise. Massapequa Park and all of Nassau County developed quickly after World War II and the proximity of houses to the airfield spurred concern among its new neighbors, who became fearful of crashes and felt inconvenienced by planes taking off and landing so close to their backyards. An additional concern developed by 1950, as the explosive growth of the school system led the board of education to look for new sites. Most streets were designated for private houses, but Fitzmaurice Flying Field was a bare space ripe for development. The school board approved a plan to buy the field and establish two schools. After several months of negotiation, they signed a contract with Tom Murphy, who agreed in April 1953 to accept $600,000 in exchange for the property. The board built Hawthorn School in 1954 at the southeast end of the field and McKenna Junior High School at the north end in 1958. Little do soccer playing youngsters know that hundreds of planes took off and landed on the fields where they play today.

George Kirchmann is a trustee with the Historical Society of the Massapequas. His email address is gvkirch@optonline.net.