By Elliot M. Kass

One of Great Neck’s oldest residents, Bernard Kass, passed away on Feb. 8. He was 96.

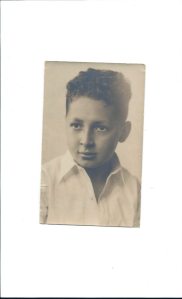

Bernie was born in 1919, on the eve of the roaring twenties, and his early years in the neighborhoods of Manhattan were shaped by that era and the Great Depression that followed.

This was a time when movies were still silent; people went to ice cream parlors because they had no way to store it at home and taking the train from Manhattan to Long Island was an all-day adventure. Bernie rooted for the New York Giants—and not the Dodgers or the Yankees—for a very practical reason: It took too long to travel to Brooklyn or the Bronx, but he and his friends could view games at Manhattan’s Polo Grounds without paying by climbing a hill that overlooked the stadium. On Saturdays, to get into the ballpark, they would pass themselves off as orphans, who were admitted for free.

Baseball wasn’t the young Bernie’s only interest. He loved sailing ships and became expert at building intricate wooden models of old schooners and frigates. He learned how to rig a model so that he could insert it into a narrow-necked bottle, and then by pulling on a thread, raise its masts so that its sails unfurled. Eventually, after moving to Great Neck, he donated two of his more elaborate models to the Merchant Marine Academy, where they are still on display.

Another pastime was the Saturday movie matinées, which featured stars like Mickey Rooney in the Andy Hardy films and cliffhanger serials like Flash Gordon. As a draw, the theaters held raffles and gave away door prizes. But this was also the start of the depression, so one time, when Bernie won the raffle, the prize turned out to be a single roller skate. What the heck do you do with a single skate? He and his friends nailed it to the bottom of an old crate to make a soapbox car and then pushed each other around the Upper West Side.

There were other, grimmer occurrences. When Bernie was 14 or 15, he hitchhiked by himself to Cleveland to visit his grandparents. En route, he flagged down a pickup truck driven by a farmer. As he started to get into the cab, the farmer told him to get into the back of the truck instead—which was filled with manure. “That’s good enough for a Jew,” the farmer exclaimed.

When he got a bit older, Bernie aspired to become an aerospace engineer and enter this new and exciting field. But his father saw things differently and took him to the East River, where Bernie’s uncle, an engineer, had a Work Projects Administration (WPA) job. He sat in a rickety old row boat all day, measuring the depth of the river with a plumb line. “Is that what you want to do?” his father demanded. So Bernie headed off to the University of Pennsylvania and its Wharton School of Business instead.

How did young college men in the late 1930s blow off steam? Not unlike today, they drank plenty of booze and chased girls. But they also engaged in the occasional prank. One time, Bernie and a group of his fraternity brothers surrounded a Philadelphia streetcar and derailed it by lifting it off the tracks. Well, boys will be boys in any era.

They will also be men. Following Pearl Harbor, Bernie joined the U.S. Army where he was trained as a code breaker. The work took him to England, Italy, Egypt and Austria, where he served under generals including George C. Marshall and George S. Patton. Stationed with the British Army while in Italy, Sergeant Kass encountered King George VI and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who were inspecting the troops. The king was aloof and off-putting, but when Sir Winston spoke, “It made the hair on the back of my neck stand up,” Bernie later recounted. “I have never met anyone else quite so impressive.”

Returning to New York at the end of the war, Bernie first worked as an accountant and then started an import-export business. It was during this time that he met Donna Sheiman, a war refugee from Warsaw, who had fled the Nazis via the Soviet Union. Bernie also got to know her brother who, as a medical student in France, joined the French Underground. Captured and tortured by the Gestapo, he survived internment at Buchenwald, the infamous concentration camp.

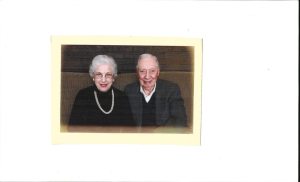

Donna’s family had narrowly made it through the war, and those memories were still fresh when she encountered this cocky young New Yorker. They made quite a pair: She still hid under tables every time a car backfired, certain it was gunfire; he treated Gotham like it was his personal oyster. But her passion for making the world a better place rubbed off on him, while his confidence and sense of certainty assured her about the future.

Married and with their first child in tow, they moved to Great Neck in 1955, where Bernie built his business and his wife practiced physical therapy. Together they raised their family and cultivated a large and ever-expanding circle of lifelong friends. Bernie supported Donna when she became an influential advocate for health care reform and a member of Nassau County’s Board of Health. And Donna was proud of Bernie when he became treasurer and a board member of COPAY, a community organization that provides treatment for drug and alcohol addiction. Together for 61 years, Bernie gave Donna an elephant figurine every wedding anniversary—a tradition dating back to their very first year of marriage.

After the kids left home and he and Donna needed more exercise, Bernie suggested they play tennis. He had been on the tennis team in college and taught his two sons to play, but he hadn’t played much himself for many years. Now in his mid 50s, he rediscovered the sport, which became an enduring passion. In recent years, Bernie was perhaps best known in Great Neck for his love of the game and as its oldest living player. He enjoyed the celebrity, a fitting denouement to a lifetime of adventure, generosity and achievement.

Bernie is survived by two sons and three granddaughters. An open-house memorial in his honor will take place on Saturday, March 19, between 2 and 5 p.m. at 50 Hillpark Ave. in Great Neck, Apt. 2H. All are welcome.

Elliot Kass, himself a longtime Great Neck resident and a product of the Great Neck schools, works as an editorial and marketing consultant. Bernie Kass was his father.

To read a story about Kass playing tennis, click here.