Hepatitis B affects more than 300 million people worldwide and more than 2 million Americans. The New York area has some of the highest rates of hepatitis B in the U.S. secondary to our diversity. Hepatitis B is a common cause of cirrhosis and the leading predisposing factor for the development of liver cancer worldwide. Unlike most other liver diseases where liver cancer usually develops after a person has developed cirrhosis, liver cancer commonly develops in patients with hepatitis B without the presence of cirrhosis.

Most people with hepatitis B are asymptomatic, so screening is important to diagnose the disease. This is very important because we no longer use the terminology of “healthy carrier” when referring to patients with normal liver enzymes and low or undetectable levels of hepatitis B virus in the blood. All patients who are not candidates for treatment at this time are now referred to as having “inactive disease”.

The goal of treatment of any infectious disease is to eradicate the infectious agent. Therefore, the goal of treatment of hepatitis B is the complete eradication of the hepatitis B virus with loss of hepatitis B surface antigen and development of hepatitis B surface antibody. Despite excellent therapies for hepatitis B, none of the currently available therapies regularly meet the goal of therapy listed above. Current anti-viral agents normalize liver enzymes, suppress hepatitis B virus in the blood and may even improve underlying liver histology. Unfortunately, these therapies, although well tolerated, need to be taken for life in most cases and the virus usually recurs with cessation of therapy. This is because hepatitis B incorporates into the nuclear material of the liver cell and therefore is extremely difficult to eradicate.

With the revolution of hepatitis C treatment and with cure rates for this disease more than 95 percent in all cases, interest is beginning to switch to the development of curative therapies for chronic hepatitis B. There are more than 30 agents currently in the development or testing stage with these agents targeting both the virus and the host.

The replication cycle of hepatitis B is well understood and has been for many years. There are many enzymes involved in both replication and transportation of the hepatitis B virus. Treatments under development include medications that prevent hepatitis B virus entry into the liver cell, inhibit viral replication at various different sites, boost host immune system responses and therapeutic vaccines.

The reality is that future treatments for hepatitis B will likely be combinations of several of the different classes of medications that have different mechanisms of action. For example, combining drugs that prevent entry of virus into the cell with those that prevent viral replication and those that boost the host’s immune system will hopefully lead to viral cure. The medication pipeline for hepatitis B is exciting and I would hope that in the next decade we could add hepatitis B to the short list of viruses that we can cure with simple, non-toxic oral medications.

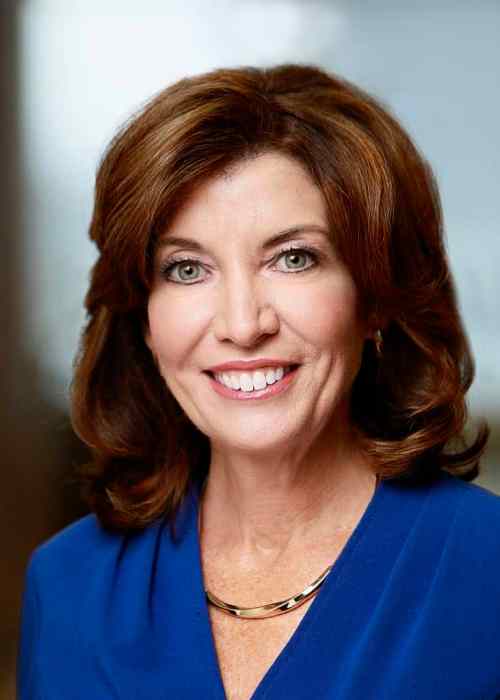

David Bernstein, MD, is chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at North Shore University Hospital and Long Island Jewish Medical Center.