One mother’s experience with autism

One mother’s experience with autism

I prefer the romantic version. “Elope” is defined by Webster’s as “to run off secretly to be married, without the knowledge or consent of one’s parents”. In the world of autism, eloping is a perplexing behavior in which the individual feels compelled to run away, and will seize any opportunity to do so.

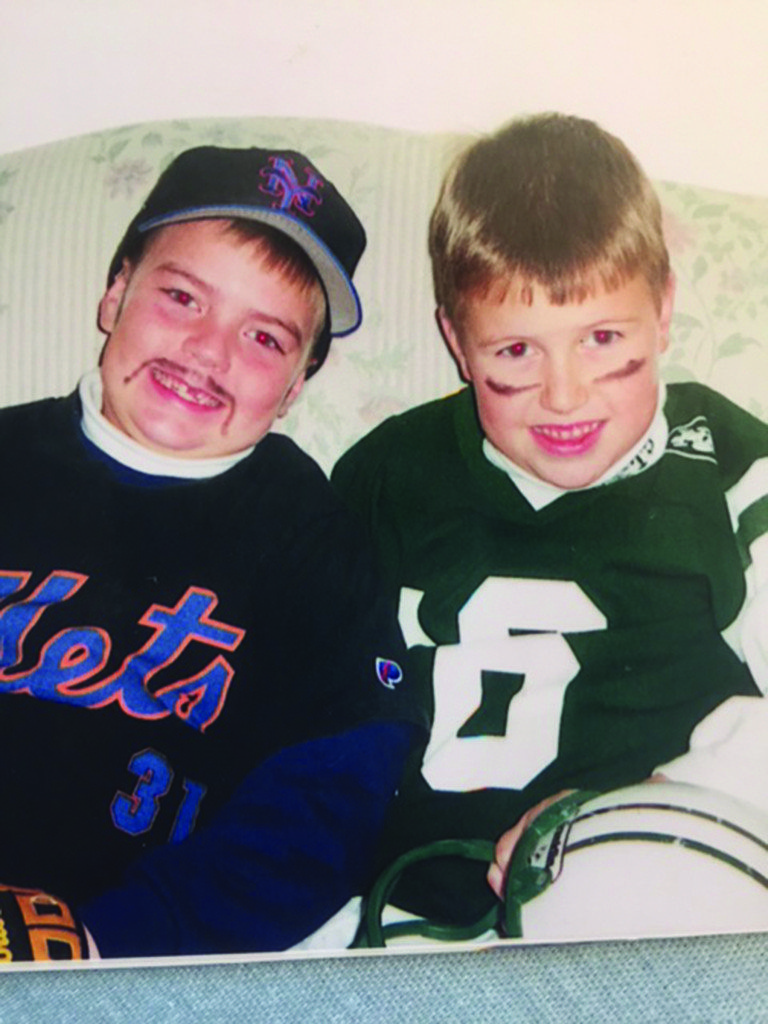

My husband pushed the wheelbarrow to and from the backyard, transporting topsoil for a new garden, while our boys played in the backyard. Joseph was proudly pumping himself on a swing, as Stuey played in the sandbox. I cleaned the dinner dishes and watched my family through a window strategically placed above the sink.

I didn’t have my eye on Stuey as intensely as usual. Stu was working right next to the only open gate, and would notice if Stuey tried to leave the yard.

“Stu, you have Stuey, right?” I asked my husband.

Stuey was in the sandbox just a few seconds prior. I stepped out onto the deck, surveying the backyard. Stuey wasn’t there. My pace increased each time I called Stuey’s name, as I began to walk through the rooms of our house. Stu joined me seconds later.

Stu and I ran through the rooms as a spinning top would through a maze. With each passing second, our voices became increasingly distressed. Stu ran outside to check the yards of our immediate neighbors. I called 911, and then frantically fumbled through our phone book and called neighbors to help us search. The Smalls, the Caiozzos, the Andersons, Calcaterras and Kathy next door. And, of course, I called Claire, my sister-in-law who lives around the corner and who had been incredibly supportive since Stuey’s diagnosis. Her children were already in bed. She sent her husband, Paul, to help.

Some jumped into their cars, others onto their bikes, and departed for each of the possible directions in which Stuey could have traveled. They took turns stopping by the house to see if he had been found.

Stu jumped in Pat Caiozzo’s mini-van, and they headed toward town. Stu and Pat had previously shared few words other than “Good Morning.” But as the minutes passed, proving their search futile, Stu and Pat began to cry.

Stu jumped in Pat Caiozzo’s mini-van, and they headed toward town. Stu and Pat had previously shared few words other than “Good Morning.” But as the minutes passed, proving their search futile, Stu and Pat began to cry.

Ten minutes since I’ve dialed 911. I walk insanely in and out of the house. “Where are the police?” I shriek as I reach for the phone.

“An officer will be there soon.”

“That’s not good enough! Don’t you understand? My son is four years old, autistic, and missing. He has no concept of danger.”

I went outside and listened for the blaring of sirens. Stuey was gone, and to get out of my neighborhood he had to cross several busy streets. He’ll get hit by a car. Surely I’ll hear sirens soon. I’ll run toward the siren, and find my son’s lifeless body on the ground. Stu and Pat pulled up. My heart sunk to my toes when I didn’t see Stuey with them.

“Where are the police?” Stu screamed.

“I called them twice. They don’t get it,” I responded.

I dragged my numb body back into the house. I can’t recall the text of the conversation when I called the police for the third time.

My hands held my shoulders, my arms crisscrossed on my chest, in an attempt to steady my shaking body. I stood outside and watched the members of our search party come and go. A neighbor asked Joseph to play inside their home, to shield him from the tragedy unfolding before us. Kathy, my next-door-neighbor, tugged on my sleeve and suggested we call the local fire department to join in the search.

At last, a single patrol car meandered up to my house. No sirens or flashing lights. I couldn’t move. The fair, young police officer picked up his notebook from the passenger seat, turned off the ignition, exited his vehicle and walked toward me. As we began to speak, I didn’t notice Paul’s car pulling up. But I will never forget the sight of Paul walking toward me, tears rolling down his face, with Stuey wrapped in his arms. He gently passed Stuey to me.

“He was down in Hill Terrace, a mile away. Someone left their backyard gate open. Stuey was playing on their swing set.” Paul struggled to speak.

“Oh well. Kids will be kids,” the officer returned to his vehicle and left. Stu and Pat returned seconds later. Stu ran to Stuey and melted in his embrace. After thanking the group of neighbors and friends gathered outside, the Manziones walked into their house, locked the door and spent the next hour in silence. You could still hear the murmur of the collection of neighbors outside our house, as we put the kids to bed. It took me a day and a half to stop shaking. A few weeks later, my good friend Rich called, knowing nothing of the events that transpired.

“I had a dream last night. A man named Claude was talking to me and said he is Stuey’s guardian angel,” Rich said.

After Rich and I spoke a bit, I hung up the phone and walked to my front door. I looked through the storm glass, in the direction of Stuey’s escape. As I imagined his mile-long journey and the busy streets he crossed, one thought came to mind: Thank you, Claude.

This story is not about autism itself, but borne out of two decades of learning about living with autism. Terri Manzione is the mother of two sons in their early 20s, one of whom is autistic. She and her husband, Stu, are involved with enhancing the plight of autistic people and furthering the cause of awareness.