Great Neck Chinese Association members share cherished memories and traditions

Compiled by Sheri ArbitalJacoby, Mimi Hu and Carey Ye

A historic decision was made this past spring. Great Neck Public Schools will be the first district on Long Island to recognize Lunar New Year—the most important celebration for the Asian community—as an official school holiday.

A historic decision was made this past spring. Great Neck Public Schools will be the first district on Long Island to recognize Lunar New Year—the most important celebration for the Asian community—as an official school holiday.

Observed on the first day of the Chinese lunar calendar, the festival, which next falls on January 28, 2017, celebrates a year of hard work and makes way for incoming good luck. Observers are meant to rest and relax with family. In modern China, workers are given seven days off to celebrate.

Some special family memories and observances from the community follow.

My husband and I come from very different backgrounds and upbringings. John is from Smithtown on Long Island and has an American father and Taiwanese mother, a brother, and two half-brothers and a sister from Taiwan. I was born in Beijing and came to New York when I was 13. Chinese New Year has always been one of the most important holidays for both our families, but we celebrated in different styles, coming from different cultures and ethnic backgrounds.

My husband and I come from very different backgrounds and upbringings. John is from Smithtown on Long Island and has an American father and Taiwanese mother, a brother, and two half-brothers and a sister from Taiwan. I was born in Beijing and came to New York when I was 13. Chinese New Year has always been one of the most important holidays for both our families, but we celebrated in different styles, coming from different cultures and ethnic backgrounds.

My fondest Chinese New Year memory from childhood would be going to temple fairs or Miao Hui in Beijing with my parents, burning incense and praying for prosperity in the new year, not to mention trying a variety of delicious traditional Chinese street food, most of which can only be found during this time, and being amused with clay figurine artists. The best part was collecting red envelopes from families upon wishing them good health and wealth for the new year.

My fondest Chinese New Year memory from childhood would be going to temple fairs or Miao Hui in Beijing with my parents, burning incense and praying for prosperity in the new year, not to mention trying a variety of delicious traditional Chinese street food, most of which can only be found during this time, and being amused with clay figurine artists. The best part was collecting red envelopes from families upon wishing them good health and wealth for the new year.

My husband and I have tried to extend this tradition and celebrate our heritage since our twin girls, Victoria and Genevieve, were born. One of our favorite activities is dumpling making, along with singing traditional Chinese ballads. With more and more Chinese immigrants moving to Long Island, for the past couple of years, we have been going to local celebrations with other families so future generations can pass on and appreciate our culture.

—ChenXin Xu-Ferguson

Although the Lunar New Year celebration varies from region to region and family to family, going home to have a sumptuous dinner, staying up, handing out hongbao (red envelopes containing cash) and paying respect to elders are the common mainstays.

Although the Lunar New Year celebration varies from region to region and family to family, going home to have a sumptuous dinner, staying up, handing out hongbao (red envelopes containing cash) and paying respect to elders are the common mainstays.

This photo depicts my Great Aunt Qiao and great uncle, who are seated with the red envelopes in hand, watching over their son and daughter-in-law with their daughter performing the kowtow ritual. After their foreheads kiss the ground three times, the elders would hand each one a red envelope that contains money.

I first encountered red-envelope etiquette after I left Beijing for Hong Kong in 1979. During the Lunar New Year, parents in Hong Kong hand out red envelopes to their children and grandchildren rather indiscriminately, but between relatives, friends or acquaintances, the receiver should be unmarried. According to the story associated with this ritual, in ancient time, there was a demon who came out on New Year’s Eve to seed bad deeds. To chase away the demon, parents place coins or knotted red string wrapped in red paper under their children’s pillow to keep them safe. Nowadays, almost all the envelopes contain money. The kids use them to their heart’s content. I heard that one set of parents put the key to a newly purchased apartment in the envelop for their daughter.

Kowtow, on the other hand, is a rare sight, because it requires the person get on his knees, and then bow low, touching his forehead to the ground. This is an excessively subservient act that was once enjoyed by the emperors when they believed they were the Son of Heaven and had no equal. The contemporary patriarch needs to have some prestige to persuade family members to participate in this ritual.

Kowtow, on the other hand, is a rare sight, because it requires the person get on his knees, and then bow low, touching his forehead to the ground. This is an excessively subservient act that was once enjoyed by the emperors when they believed they were the Son of Heaven and had no equal. The contemporary patriarch needs to have some prestige to persuade family members to participate in this ritual.

When Lord Macartney paid China a visit on behalf of King George III in 1793 seeking to establish a trade and diplomatic relationship, kowtow was the thorny issue that both sides haggled over fiercely. Emperor Qianlong regarded them as barbarian and his entourage as ordinary, while Lord Macartney saw China and Britain as equal monarchs.

When my father was a teenager he lived in Wanzhuyuan, Ten Thousand Bamboo Garden in Ji’nan, with his extended family including Great Aunt Qiao, on every Lunar New Year’s Eve, they would feast on a lavish dinner and then go on a vegetarian diet for the next five days, during which time the servants would not be allowed to sweep the floor. There was no cooking for the entire month, only heating up was allowed. The servants were always busy preparing the monthlong no-raw food period leading up to the new year. After dinner, they would queue up at the shrine in the Pomegranate Tree Courtyard, taking turns to kowtow to his grandfather and Great Aunt Qiao’s father. As adults, they both fondly remembered discretely placed red envelops under their pillows. It’s fun for youngsters to wake up and find the lucky money to start a new year.

Since 1984, the Ten Thousand Bamboo Garden has become a public park. This year when I accompanied my father and Great Aunt Qiao on a visit, I paid an entrance fee, but they didn’t—not because they lived there, but due to the seniors’ free park perk.

After Deng Xiaoping regained power the third time in 1980, the Chinese people gradually started embracing the old customs that once flourished for thousands of years that had been banned briefly during Mao’s reign. As China prospers, Great Aunt Qiao reintroduces our family traditions. She gathers her children, grandchildren, and as of 2015, her great grandson, for the celebration. Beginning on New Year’s Eve with a luxurious dinner, which is sometimes home cooking and sometimes in a restaurant, follow by majiang and card games while watching the CCTV New Year’s Gala that‘s commonly known as chunwan. Staying up on New Year’s Eve is called shousui or aonian. For elders, it’s to cherish time past and for the younger generations, it’s symbolic as to extend their parents’ longevity. When the pendulum glides over 12 at the top of the clock that ushers in the brand new year, each individual family, dad, mom and child, takes turn to kneel down, performing kowtow to her and her husband, as you see in the picture.

—Irene Eng

Everyone who works away from their hometown comes back to celebrate Chinese New Year. We would prepare a table full of dishes and enjoy the food with the whole family while watching the CCTV Spring Festival Gala. As it approached 12 a.m., we would set off fireworks to say goodbye to the old and welcome in the new.

Everyone who works away from their hometown comes back to celebrate Chinese New Year. We would prepare a table full of dishes and enjoy the food with the whole family while watching the CCTV Spring Festival Gala. As it approached 12 a.m., we would set off fireworks to say goodbye to the old and welcome in the new.

On the first day of the New Year, we enjoy a bowl of sweet dumplings made from sticky rice. The round shape symbolizes our hope for a full and prosperous New Year.

The first month of the New Year is a time when families visit one another and offer their best greetings for the coming year. Everybody is so joyful and cheerful.

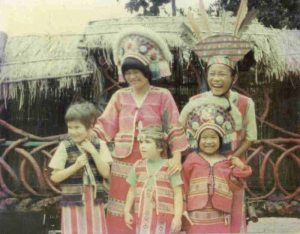

Communities organize events and games for everyone to enjoy. In the picture above, a show is being put on by our community in front of a supermarket. A pretty girl stands in the middle of a make-believe boat made from paper and hemp. The gestures of the people around her express that they are pretending to row the boat. The people around the boat are singing songs, which is meant to bring good futures. They say “bai nian” to wish each store a good year. The store owners respond by saying “hong bao” to return their wishes.

Older generations give hong bao (red envelopes) to younger generations. It doesn’t matter how much money is inside; the greetings and wishes it embodies are far more important. We also give hong bao to the elders to wish them longevity. We also hang big red lanterns from

Older generations give hong bao (red envelopes) to younger generations. It doesn’t matter how much money is inside; the greetings and wishes it embodies are far more important. We also give hong bao to the elders to wish them longevity. We also hang big red lanterns from

the roof of our house, because red symbolizes prosperity.

—Camille Wu

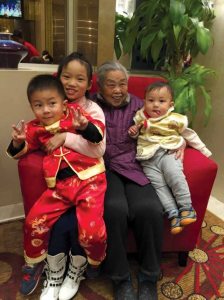

The Lunar New Year has been the most cheerful and blissful holiday throughout my entire childhood. It’s the biggest day of the whole year. Everyone in the family, no matter how far apart they are during the rest of the year, will try their best to get together for this traditional holiday. Families want to celebrate together and wish one another good luck for the coming year. In the picture at right, my sons, Charlie and Henry, and my niece Jiajia went to Shenzhen to celebrate Lunar New Year with their great grandma.

The Lunar New Year has been the most cheerful and blissful holiday throughout my entire childhood. It’s the biggest day of the whole year. Everyone in the family, no matter how far apart they are during the rest of the year, will try their best to get together for this traditional holiday. Families want to celebrate together and wish one another good luck for the coming year. In the picture at right, my sons, Charlie and Henry, and my niece Jiajia went to Shenzhen to celebrate Lunar New Year with their great grandma.

Red envelopes are an important symbol during the Lunar New Year. The amount of money in them doesn’t matter; it’s more of a meaningful wish of good luck and smooth sailing for the new year. Red pockets are not only given by the elders to the children but also vice versa. Ya sui or money is given to wish the elders another healthy and peaceful year.

—Si Wen

This story appeared in Great Neck Magazine. See the full issue here.