You can’t really call Thomas Pynchon the Greta Garbo of American literature. There are actual photos of the reclusive screen star. Nor can you say he’s the J.D. Salinger of modern literature. Salinger, too, was briefly a public figure. Since his 1963 publication of V., Pynchon, who was born in Glen Cove and who graduated from Oyster Bay High School, has been both the most reclusive figure in American literature, while remaining on the cutting edge of modern fiction.

This past May, Pynchon celebrated his 80th birthday. Following the publication of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), Pynchon was the most celebrated fiction writer of his time, with that ambitious novel declared as the finest work of fiction to come out of the 1970s. Pynchon is Long Island’s most accomplished literary figure since Walt Whitman. Unlike the Good, Gray Poet, there aren’t any highways or boulevards or high schools named for the man. Still, Pynchon is one of the most influential novelists of our time, as generations of fiction writers have long hailed him as an important innovator in the development of the novel.

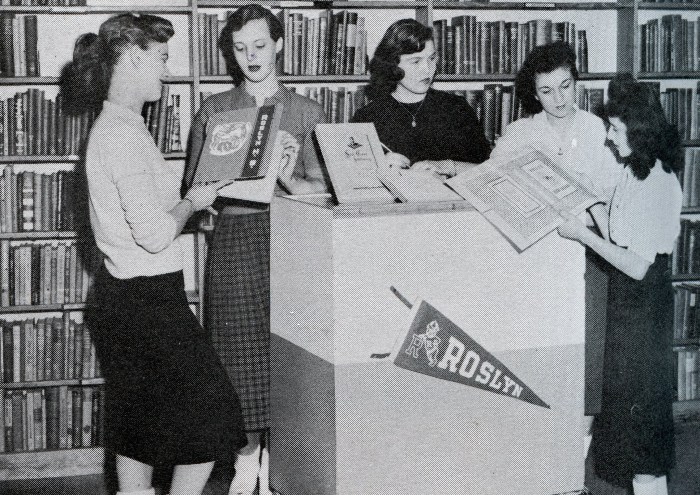

Pynchon’s style is postmodern, a form of literature that emerged in the post-World War II era, where satire, black humor, surrealism and despair, rather than a more conventional social realism wrought with moral themes, sought to illuminate the times. Pynchon was a natural writer, proving, once again, that creative writers are born, not made, even though the actual work is long and strenuous and generally unrewarding. A high school student in the 1950s, Pynchon displayed a talent for writing, contributing short fiction to the school newspaper. After a stint in the U.S. Navy, Pynchon enrolled at Cornell University, where he studied under the legendary Russian novelist, Vladimir Nabokov, a writer who also excelled in gallows humor and unconventional story lines. At Cornell, Pynchon became friends with Kirkpatrick Sale, later a prolific social critic. As important was his friendship with Richard Farina, who later penned an acclaimed cult novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me (1966). Pynchon would become more prolific than Farina, a man who died at age 29 in a motorcycle accident, but Pynchon, it can be said, looked up to Farina. He even dedicated Gravity’s Rainbow to the late novelist.

Pynchon’s style is postmodern, a form of literature that emerged in the post-World War II era, where satire, black humor, surrealism and despair, rather than a more conventional social realism wrought with moral themes, sought to illuminate the times. Pynchon was a natural writer, proving, once again, that creative writers are born, not made, even though the actual work is long and strenuous and generally unrewarding. A high school student in the 1950s, Pynchon displayed a talent for writing, contributing short fiction to the school newspaper. After a stint in the U.S. Navy, Pynchon enrolled at Cornell University, where he studied under the legendary Russian novelist, Vladimir Nabokov, a writer who also excelled in gallows humor and unconventional story lines. At Cornell, Pynchon became friends with Kirkpatrick Sale, later a prolific social critic. As important was his friendship with Richard Farina, who later penned an acclaimed cult novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me (1966). Pynchon would become more prolific than Farina, a man who died at age 29 in a motorcycle accident, but Pynchon, it can be said, looked up to Farina. He even dedicated Gravity’s Rainbow to the late novelist.

From the start, Pynchon displayed impressive energy. After college, Pynchon worked as a technical writer for Boeing in Seattle, WA. But he didn’t waste his evening watching television. Instead, he plunged forward with his fiction, writing and publishing V., a novel that drew from the author’s earlier life in the Navy. V. won a William Faulkner Foundation Award for best first novel of the year. This allowed Pynchon to resign from Boeing and begin writing full time. In 1966, he published his second novel, The Crying of Lot 49, another black humor effort about a corporation that uses the bones of dead American GIs to make cigarette filters. That novel won the Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award.

All the while, Pynchon was living in southern California and working on Gravity’s Rainbow. The novel, when published in 1973, was a best seller that solidified Pynchon’s position as the leading postmodern novelist. With its World War II setting and themes highlighting the dehumanizing aspects of the total warfare that characterized the final stages of that war, the novel is similar to Kurt Vonnegut’s more accessible Slaughterhouse Five. Both novels appeared at an opportune time, when disillusionment with the Vietnam War was at its peak and war itself in a world made by mass technological advances seemed more barbaric than ever. At the same time, the novel had its critics. It won the National Book Award, but was rejected for the Pulitzer Prize, with some judges claiming that the novel was, “unreadable,” “turgid” and “overwritten.”

His reputation secure, Pynchon took some time off from publishing. He also remained a recluse. In the mid-1970s, The Soho Weekly News ran an article that claimed that J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon were one in the same man, that Salinger was now using “Thomas Pynchon” as his author’s name. After discovering the article, Pynchon reportedly wrote back to the publication, telling them, “Not bad. Keep trying.” And indeed, throughout the 1970s, that gold-colored paperback edition of Gravity’s Rainbow was as commonplace as the maroon-colored paperback of Catcher In The Rye. Either way, the article only highlighted the growing mystique around Pynchon. At a time when novelists expertly used the mass media to bring attention to their work, Pynchon was doggedly reclusive. And that’s the way it would stay.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, Pynchon resumed publishing. In 1984, he published Slow Learner, a collection of early short stories. The coming years would bring a number of ambitious novels on the scale of V. and Gravity’s Rainbow: Vineland (1990), Mason & Dixon (1997), Against The Day (2006), Inherent Vice (2009) and Bleeding Edge (2013). Reviewers made the same criticism of some of these novels as they had of Pynchon’s earlier works, namely they could be rambling and overwritten. Still, Pynchon’s legend made each a literary event. Pynchon’s most recent novel, Bleeding Edge, is also his most conventional work of fiction, an entertaining story of a single mother of two living on the Upper West Side who makes a living as a daring private investigator. An angry young man who raged against the world he was born into, Pynchon has cooled in his later years.

Pynchon was a product of the booming postwar world on Long Island. He also grew up in the shadow of World War II , a generation that later collided head-on with the Vietnam War. As with any fiction writer, he was shaped by the times. And so, his fiction is concerned with the impact of a material world on the human soul. The results are not terribly optimistic. Still, his style has been contagious, influencing a number of prominent novelists, among them Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Salman Rushdie and Rick Moody.