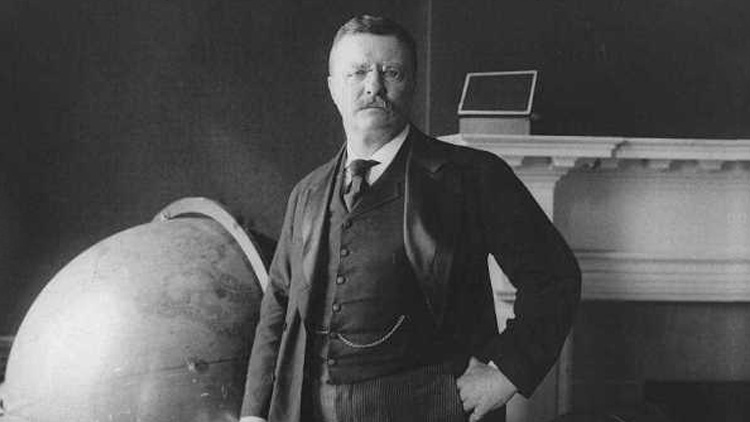

He started life as a sickly, asthmatic child, confined to his bed. But illness didn’t stop him: Before reaching the age of 42, he had become the 26th president of the United States — the youngest person to hold that title.

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was a strong-willed natural leader who embraced constant challenges. Dubbed the “conservation president,” he went up against timber barons to establish the U.S. Forest Service and hundreds of national forests, bird reserves, game preserves, and national parks, while protecting 230 million acres of public land. He signed into law the Antiquities Act to protect archaeological sites and monuments.

And yet, this nature worshipper was an obsessive hunter who tracked grizzly bears, stalked endangered white rhinos, and killed hundreds of animals — not all in the name of science.

THE STRENUOUS LIFE

Born in 1858 in a New York City brownstone, “Teedie” grew up thirsting for adventure. The bright 8-year-old preserved specimens and founded the “Roosevelt Natural History Museum” in his bedroom. He read obsessively, and by age 11 was writing essays on insects.

His merchant-philanthropist father, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., helped found the American Museum of Natural History in 1869. Teedie later donated his childhood natural history cabinet, containing thousands of animal specimens, to the museum. Encouraged by his parents to exercise, Teedie improved his health through the “strenuous life.”

He hiked, rode horses, and swam during summers around Cove Neck and at Tranquility, his family’s summer home in Oyster Bay. He hoped to become a naturalist and studied natural history and zoology at Harvard University.

After graduating magna cum laude in 1880, TR purchased land in Cove Neck for a home for his new wife, Alice Hathaway Lee.

THE HUNTER-CONSERVATIONIST CONUNDRUM

Enrolling in Columbia Law School, he dropped out in 1882 to pursue public service as a Republican. But his ambitions were crushed in 1884, when his mother and his wife both died, on Valentine’s Day.

The political life could not ease his grief. He headed for the Dakota Badlands, a buckskin-clad, New York City tenderfoot who reined in his sorrow by living in the saddle and hunting big game.

Roosevelt’s hunting passion was shaped by Victorian attitudes. Feathers and dead bird parts adorned women’s hats and boas, while gentlemen hunters embodied “all the qualities of the idealized, rugged, independent American,” as described in Environment and Society. Big-game specimens were collected — killed — to become trophies. Despite poor eyesight, Roosevelt loved the chase; he later recalled a group safari that “made our veins thrill.”

In 1885, on one of the last Dakotas buffalo hunts, he shot a bison, but the injured creature was never found. After several years he came home to pursue politics, married Edith Carow, and settled at Sagamore Hill. By age 25, TR was a three-time New York State assemblyman. He served as a reformer — on the Civil Service Commission, as police commissioner, assistant secretary of the Navy, governor of New York and vice president.

When President William McKinley was assassinated, Roosevelt assumed the office and curbed corporate power as a trust- buster. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1906 for brokering an end to the Russo-Japanese War.

As President from 1901 to 1909, he fought for wilderness preservation — and he hunted. On one 1909 safari, the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition, more than 11,000 animals were donated for taxidermy. Roosevelt and his son Kermit shot 512 animals, from aardwolves to zebras, many at excessive ranges. Author Bartle Bull wrote in time.com that the safari outfitter described “the slaughter which [Roosevelt] and his party perpetrated.”

This was the Jekyll and Hyde duality of Theodore Roosevelt. Today, his many supporters flock to his sprawling North Shore estate Sagamore Hill, where he lived from 1885 until his death in 1919. They view original furnishings and mementos throughout the 23-room Queen Anne home surrounded by forests and salt marshes. They absorb stories about the international dignitaries who visited this Summer White House from 1902 to 1908.

And they stare at his abundant hunting souvenirs — once-majestic creatures on display, now stuffed and silent — trying to understand the figure who is both revered and reviled.