In the mid-1960s, Greenwich Village mirrored the polarized nation. Political upheaval and the sexual revolution set the scene for Lou Reed to turn music on its ear with the Velvet Underground and the support of pop artist Andy Warhol.

“They were … countercultural cool,” wrote Rolling Stone. “Not the Haight-Ashbury or Sgt. Pepper kind but an eerier, artier, more NYC-rooted strain.”

After six years, frontman Reed played his last Velvets gig at Manhattan’s Max’s Kansas City in 1970. He walked away from the group called the most influential American band of the late 1960s and early 1970s — but his demons walked with him.

WALK ON THE WILD SIDE

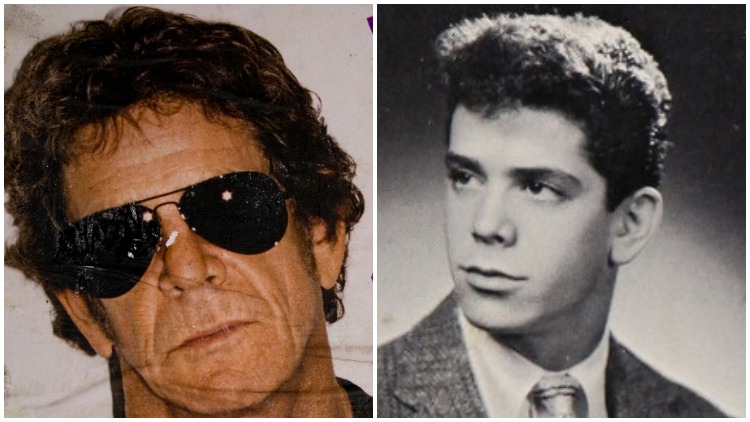

Performing solo, the singer-songwriter-guitarist-poet delivered brooding, half-spoken, half-sung verse. He personified coolness, signing letters “The Coolest Man in the World.”

But the hipster was a suburbanite. He was born in Brooklyn in 1942, then his family moved to a modest ranch-style home in Freeport, where he attended Atkinson Elementary School, Freeport Junior High and High School, where he played R&B and rock in bands. The English major with attitude was one of the brilliant Jewish kids who frequented the Village and wanted to be beatniks.

After his 1959 graduation, he struggled academically at Syracuse University, so he was sent home. His depression and sexual adventures frightened his parents — Reed later said he knew he was bisexual in high school — who subjected him to electroconvulsive therapy.

Reed returned to Syracuse. Despite his drug use, he graduated with honors. He got a job at Pickwick Records, where he met Welsh musician John Cale, the Velvets’ co-founder. Reed later recalled that at Pickwick, “They’d say, ‘Write 10 surfing songs …’ and I wrote ‘Heroin.’”

In 1972, RCA released his second album with its hit, “Walk on the Wild Side,” about drugs, transsexuals, prostitutes, and oral sex (RCA deleted the oral sex references).

Like Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, Reed wrote about the city’s seedy underbelly: junkies, hookers, and other outsiders. Reed walked the walk, reportedly vowing to take meth every day for the rest of his life. Onstage, wrapping a microphone cord around his arm, he pretended to shoot up.

LIFE OF CONTRADICTIONS

Reed was lauded and damned. Rolling Stone praised him for fusing “street-level urgency with elements of European avant-garde music.” Writer Ed McCormack called him “one of the ballsiest dudes I ever knew — the chameleon who taught Jagger, Bowie, the New York Dolls, and a whole generation of swaggering rock ’n’ roll peacocks how to ‘put their girl on’ without sacrificing their manhood.”

Others labeled Reed a privileged suburban rich kid. A posturing public junkie. A monster, said biographer Howard Sounes, “a suspicious, cantankerous, bitter, angry man.” Reed allegedly slapped women, pulled fans’ hair, and pulled a switchblade on his violin player.

Biographer Anthony DeCurtis told The Guardian that Reed was very private and “had a very complicated relationship with his own history and his own, often contradictory, desires.” He added that Reed tried to convey a “leather‑clad invulnerability,” but there was a lot of insecurity underneath that. DeCurtis added that after a signing for Reed’s book of lyrics, Reed wept, moved at having people say how much his work meant.

In 2012, he was recognized by U.S. and European researchers who named a new genus of spiders in Israel after him. Loureedia annulipes is a velvet spider that lives underground.

TOUGH, GRITTY, AND SWEET

Reed’s career spanned four decades. In 1992, he met performance artist-musician Laurie Anderson, after getting clean in the 1980s; they spent 21 years together. Anderson described him as “the sweetest, most tender person.”

But addiction had done its damage. He spent his last days in East Hampton, a tai chi master who was “happy and dazzled by the beauty and power and softness of nature,” Anderson remembers.

In May 2013, after chronic liver failure, he had a liver transplant at the Cleveland Clinic. He died from complications five months later.