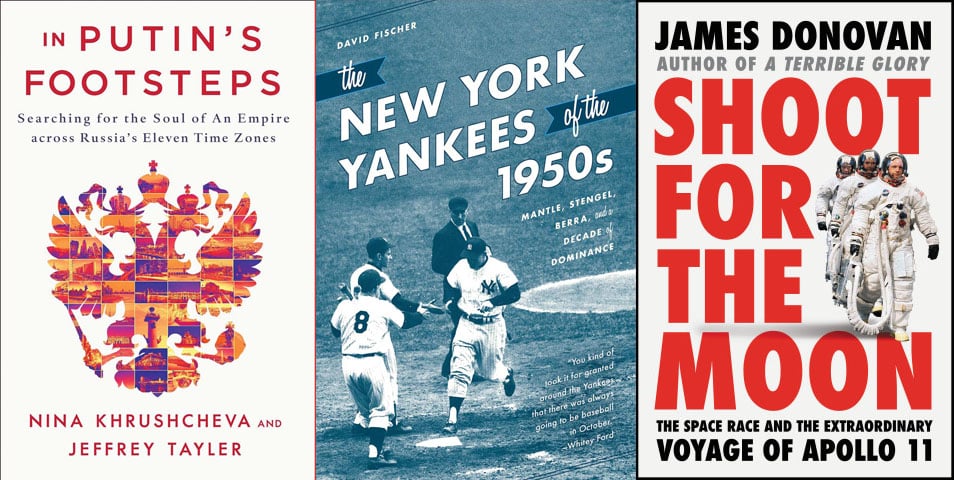

The 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s Apollo 11 moon landing and walk is upon us. So far, there has been a film, First Man, which received poor reviews, and a documentary, Armstrong, which fared better. James Donovan’s Shoot For The Moon also celebrates the moon landing, even though most of the book is a history of the Mercury-Gemini program that preceded it. Donovan tells a familiar story: The Sputnik shocker, where Americans literally feared Soviet domination of both space and earth, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson’s dedication to space travel (along with Dwight Eisenhower’s ambivalence), John Glenn’s heroics, the central role of Wernher Von Braun, the German émigré and mastermind of the legendary V-2 rocket, Armstrong himself, whose humility made him the right choice to be the first man to step on the moon and the achievements of a 24-year-old computer whiz kid named Jack Garman. What is stunning is the pessimism among NASA technicians and the astronauts. The Apollo 11 crew gave themselves only a 50-50 chance of success, which meant that Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin could have perished on the cold lunar surface.

The 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s Apollo 11 moon landing and walk is upon us. So far, there has been a film, First Man, which received poor reviews, and a documentary, Armstrong, which fared better. James Donovan’s Shoot For The Moon also celebrates the moon landing, even though most of the book is a history of the Mercury-Gemini program that preceded it. Donovan tells a familiar story: The Sputnik shocker, where Americans literally feared Soviet domination of both space and earth, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson’s dedication to space travel (along with Dwight Eisenhower’s ambivalence), John Glenn’s heroics, the central role of Wernher Von Braun, the German émigré and mastermind of the legendary V-2 rocket, Armstrong himself, whose humility made him the right choice to be the first man to step on the moon and the achievements of a 24-year-old computer whiz kid named Jack Garman. What is stunning is the pessimism among NASA technicians and the astronauts. The Apollo 11 crew gave themselves only a 50-50 chance of success, which meant that Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin could have perished on the cold lunar surface.

When people speak of the world’s largest nation, they no longer say “Russia.” Instead, it’s “Putin’s Russia,” a sentiment reflected in the title of Nina Khruscheva and Jeffrey Tayler’s travel book, In Putin’s Footsteps: Searching For The Soul of the Empire. Khruscheva, as the reader might guess, is the granddaughter of the former Soviet premier, the famous shoe-banging Nikita Khrushchev. This gives the book an emotional appeal. Khruscheva lives in self-imposed exile in New York. She loves her homeland and is at turns, both disappointed by its stubbornness to go full Western, while being inspired by the pride ordinary people take in their hometowns.

When people speak of the world’s largest nation, they no longer say “Russia.” Instead, it’s “Putin’s Russia,” a sentiment reflected in the title of Nina Khruscheva and Jeffrey Tayler’s travel book, In Putin’s Footsteps: Searching For The Soul of the Empire. Khruscheva, as the reader might guess, is the granddaughter of the former Soviet premier, the famous shoe-banging Nikita Khrushchev. This gives the book an emotional appeal. Khruscheva lives in self-imposed exile in New York. She loves her homeland and is at turns, both disappointed by its stubbornness to go full Western, while being inspired by the pride ordinary people take in their hometowns.

The authors acknowledge Putin’s enduring popularity. Defeat in the Cold War was a humiliating experience. Russia, like the United States, China or India, is not so much a nation as a world unto itself. Full integration into an American-German-dominated West is not in the cards. The final line leaps out: Russia remains a nation where “the past is anything but past.” It reminds one of Faulkner’s observation, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” Happy is the nation where its people have both feet firmly planted in a past, one both heroic and tragic.

No team, save the Boston Celtics of 1957 to 1969, ever dominated sports as did the New York Yankees of the 1950s. By 1950, Joe DiMaggio’s career was winding down. Yankees management, led by the indefatigable George Weiss, kept the dynasty running on all cylinders. Weiss and his scouts signed hundreds of young men to meager contracts. Then it was off to Arizona to see which ones would stick. In the spring of 1951, the young Mickey Mantle kept bashing 500-ft. and 600-ft. home runs. That was the idea. One of these young men were certain to have the goods. Yankee management also liked the way Casey Stengel, while managing in the minor leagues, related well to young players. Weiss was looking for a teacher as manager. By platooning his players and using starting pitchers in tight spots in World Series games, Stengel out-managed his competitors at every turn. The Yankees were brilliant up the middle: Yogi Berra behind the plate, Phil Rizzuto at shortstop, Jerry Coleman and Billy Martin at second base, Mantle in center field and the trio of Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds and Eddie Lopat on the mound. But Weiss and Stengel’s ruthlessness kept the team sharp. This quickie book fails to capture the drama of the Yankee dynasty, especially its finest hour: Wins on the road in Brooklyn in Games Six and Seven of the 1952 World Series, where Stengel ran circles around Dodger skipper, Chuck Dressen, plus the comeback win over the Milwaukee Braves in the 1958 fall classic. In the blandly-titled The New York Yankees of the 1950s: Mantle, Stengel, Berra, and a Decade of Dominance, David Fischer takes a look at the decade and doesn’t like what he sees. The book, then, becomes a running commentary on the Eisenhower years, rather than sticking to baseball. Peter Golenbock’s Dynasty remains the book to read on this unforgettable era in Yankee history.

No team, save the Boston Celtics of 1957 to 1969, ever dominated sports as did the New York Yankees of the 1950s. By 1950, Joe DiMaggio’s career was winding down. Yankees management, led by the indefatigable George Weiss, kept the dynasty running on all cylinders. Weiss and his scouts signed hundreds of young men to meager contracts. Then it was off to Arizona to see which ones would stick. In the spring of 1951, the young Mickey Mantle kept bashing 500-ft. and 600-ft. home runs. That was the idea. One of these young men were certain to have the goods. Yankee management also liked the way Casey Stengel, while managing in the minor leagues, related well to young players. Weiss was looking for a teacher as manager. By platooning his players and using starting pitchers in tight spots in World Series games, Stengel out-managed his competitors at every turn. The Yankees were brilliant up the middle: Yogi Berra behind the plate, Phil Rizzuto at shortstop, Jerry Coleman and Billy Martin at second base, Mantle in center field and the trio of Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds and Eddie Lopat on the mound. But Weiss and Stengel’s ruthlessness kept the team sharp. This quickie book fails to capture the drama of the Yankee dynasty, especially its finest hour: Wins on the road in Brooklyn in Games Six and Seven of the 1952 World Series, where Stengel ran circles around Dodger skipper, Chuck Dressen, plus the comeback win over the Milwaukee Braves in the 1958 fall classic. In the blandly-titled The New York Yankees of the 1950s: Mantle, Stengel, Berra, and a Decade of Dominance, David Fischer takes a look at the decade and doesn’t like what he sees. The book, then, becomes a running commentary on the Eisenhower years, rather than sticking to baseball. Peter Golenbock’s Dynasty remains the book to read on this unforgettable era in Yankee history.

In his quick overview of American history (If We Can Keep It: How the Republic Collapsed and How It Might Be Saved), Michael Tomasky also doesn’t like what he sees from the past. Before listing areas of reform, Tomasky walks the reader through a brief tour: Ages of Creation, Power, Consensus and Fracture. Tomasky believes the revolutions of the 1960s, ’70s and beyond were necessary, but he remains incensed at the ongoing backlash. America, the author admits, has come apart on issues of race, gender and immigration. He fails to add that the American family has also collapsed. The Age of Consensus had this: The family unit meant husband, wife and children. Tomasky holds out hope that the Age of Fracture is succeeded by an Age of Repair. His pie-in-the-sky includes a foreign exchange-style student program for youngsters from red and blue states, a compulsory service year for college students, an expanding civics education (one that “means neither glossing over the bad [aspects of American history] nor overemphasizing it”) and a “demand” for social responsibility by corporate and business leaders. Tomasky calls for abolishing the electoral college. Citing one Jefferson Cowie, he acknowledges that the Age of Consensus (1929 to 1960) only happened because the United States remained a homogeneous nation, prosperous enough to give in a little.

In his quick overview of American history (If We Can Keep It: How the Republic Collapsed and How It Might Be Saved), Michael Tomasky also doesn’t like what he sees from the past. Before listing areas of reform, Tomasky walks the reader through a brief tour: Ages of Creation, Power, Consensus and Fracture. Tomasky believes the revolutions of the 1960s, ’70s and beyond were necessary, but he remains incensed at the ongoing backlash. America, the author admits, has come apart on issues of race, gender and immigration. He fails to add that the American family has also collapsed. The Age of Consensus had this: The family unit meant husband, wife and children. Tomasky holds out hope that the Age of Fracture is succeeded by an Age of Repair. His pie-in-the-sky includes a foreign exchange-style student program for youngsters from red and blue states, a compulsory service year for college students, an expanding civics education (one that “means neither glossing over the bad [aspects of American history] nor overemphasizing it”) and a “demand” for social responsibility by corporate and business leaders. Tomasky calls for abolishing the electoral college. Citing one Jefferson Cowie, he acknowledges that the Age of Consensus (1929 to 1960) only happened because the United States remained a homogeneous nation, prosperous enough to give in a little.