The deadly disease originated in Asia, roared through Eastern Europe, and killed nearly half of those affected. But officials downplayed the danger and the voracious germ shadowed everyone, rich or poor. Still, people kept traveling.

This isn’t yet another rehash of the early stages of the novel coronavirus in China and how world governments handled — or mishandled — what rapidly became a pandemic. It’s the older story of how travelers, including immigrants bursting with hope for new lives, boarded steamships bound for New York City in 1892 but fell ill en route and died.

The cause: the bacterial pandemic cholera. As panic overtook compassion, armed Long Island residents and baymen stormed Fire Island’s Surf Hotel to block the passengers’ death ship from docking.

SILENT STOWAWAY

In late August 1892, five ships sailing from Hamburg, Germany were part of America’s great immigration wave between 1880 and 1930 — more than 27 million people. Seeking work, fleeing famine and religious oppression, they were desperate to escape Europe’s fifth cholera pandemic.

Many of the immigrants on those ships were crammed into overcrowded lower-class steerage, while Americans and others luxuriated in upper-class cabins. But none of them realized that a highly infectious silent stowaway was sharing their quarters. During the journey, passengers showed symptoms — watery diarrhea, vomiting, and low blood pressure — caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium found in water contaminated with feces.

There was no treatment and no cure for the scourge that thrived on overcrowding, poverty, and inadequate sanitation facilities. Like today’s coronavirus pandemic that stranded infected cruise ships at sea, cholera left 19th-century steamships anchored off coasts, denying them entry to port, or forced them to dock with afflicted passengers aboard.

When New Yorkers learned that five steerage and first-class passengers had died aboard the disease-ridden Normannia which planned to dock on Sept. 3, they panicked. Public health officials knew that those with symptoms needed isolation, so they moved afflicted passengers — mostly steerage immigrants — to Lower New York Bay’s Swinburne Island’s hospital tents.

The people with no symptoms, mostly the wealthy, were to be quarantined on board for 20 days. But when several of the ship’s steam-boiler stokers contracted cholera, the wealthy cabin passengers rejected quarantine on the pest ship. The solution? Move them into a once-grand, sprawling Fire Island hotel.

The 500-room hotel was originally opened in 1858 in Kismet by New York City hotelier David S.S. Sammis, hosting the rich and famous and their yachts during the Gilded Age, but within three decades it had deteriorated. Its isolated location convinced officials to buy it to quarantine healthy passengers.

New York State Democratic Gov. Roswell P. Flower put down $50,000 of his own money and the hotel was purchased on Sept. 10 for $210,000. The next day, cabin-class passengers were transferred to the pleasure boat the Cepheus. Destination: the Surf Hotel on the South Shore near Islip, just a few hours away.

As journalist Abraham Cahan wrote, “For the rich first-class passengers they bought a hotel, and for the paupers, they put up military tents on a field in which they set up beds.”

NIMBYS REVOLT

The trip took nearly three days, with more than 500 passengers stuck on an overcrowded day boat lacking sleeping quarters and food. What caused the delay?

Fear. Islip residents, dubbed “clam diggers” by the press, worried about cholera’s spread. Baymen feared for their livelihood after standing orders of the Great South Bay’s fish and oysters were cancelled. Supporting its citizens, Islip officials secured a court injunction to block the health department from using Fire Island for quarantine.

But there was more to the uprising than fear of disease. The late 19th century’s mass influx of people who brought in unfamiliar languages, customs, and religions — and competition for jobs — led to widespread distrust of immigrants by native-born Americans, stoking the fires of prejudice against those perceived to be a threat: foreigners.

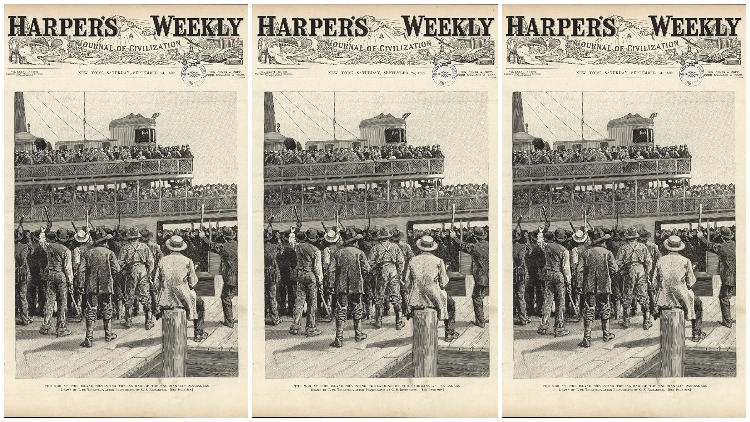

Many harbored the belief that immigrants and disease were linked. Correspondent Casper Whitney, on board the Cepheus to chronicle events, expressed what many thought: “Let there be a suspension of immigration,” in the ending of his Harper’s Weekly essay.

Angry, armed with clubs and shotguns, at least 100 fearful citizens and baymen from Islip, Bay Shore, and Babylon crossed the bay in boats. They formed a mob around the hotel pier, shouting “Go back to Europe!” to prevent the quarantine ship from docking.

On Sept. 13, Gov. Flower dispersed the mob by threatening to dispatch the infantry and naval reserves. A few days later, the injunction against the ship’s landing was dissolved by a higher court ruling: The state’s authority prevailed in matters of public health.

During quarantine at the hotel, two cases of cholera were reported. They turned out not to be cholera, but the hotel never recovered from its ordeal. In 1908, the hurricane-ravaged hotel became the first state park; today it is part of Robert Moses State Park.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here.