The history books have always told us how the first official recognition of a national Thanksgiving holiday came about.

On Oct. 3, 1789, in New York City at Congress’s request, President George Washington issued the first formal proclamation of Thanksgiving in the United States, “President Washington’s National Thanksgiving Proclamation.” Henceforth, he said, the country would celebrate an annual day of public gratitude.

Not so fast, George: An Oyster Bay schoolmaster living on Long Island’s North Shore beat you to it. Thanks to Zachariah Weekes’ 18th century diary entry and a local historian’s modern-day sleuthing, we now know that New Yorkers’ first annual observance actually took place in 1759 — 30 years before the president’s proclamation, before there even was an American president or a United States.

THE PROOF IS IN THE PUBLISHING

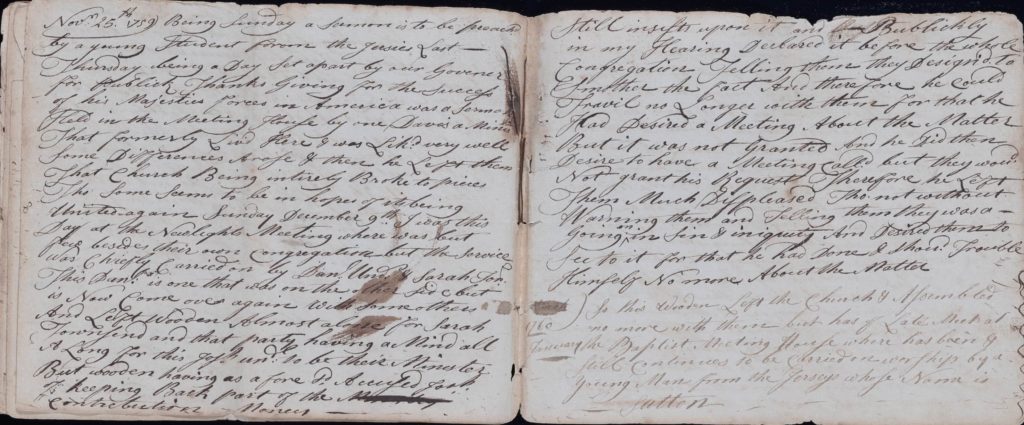

The discovery in November 2018 of the faded, ink-stained pages was a major find for Claire Bellerjeau, director of education at the Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay. The entry in the sheepskin diary she discovered in the museum’s archives was written by hand in the flowing, ornate cursive of the day, dated Sunday, Nov. 25, 1759, and is the earliest known mention of Thanksgiving in the state.

At a time when there was no standardization of holiday dates, Weekes wrote that the first Thanksgiving took place several days earlier, on Nov. 22, as proclaimed by New York State’s acting Governor James DeLancey: “…Last Thursday being a day set apart by our Governor for publick Thanksgiving for the Success of his Majesties Forces in America …”

Who was Zachariah Weekes? He was Oyster Bay’s schoolmaster for 14 years. He took lodging in the Underhill house between Cove Road and Tiffany Road, and was a keen observer of life around him in Oyster Bay in Queens County, before Nassau County was created. He wrote about the busy maritime activity, the likelihood of smallpox spreading, the Seven Years’ War between the British and the French, religion, and the church.

And he wrote about his students and their prominent LI families — the Townsends, Underhills, Youngs, McCouns, and more — who paid for their children’s tuition in goods including hardware, food, clothing, and, of course, “oisters,” rather than in coin.

Weekes’ diary was never published, but there was other evidence — published proof — of the date he specified, according to Bellerjeau.

“I did find a corresponding record for the Nov, 22, 1759 Thanksgiving date,” she said, referring to an advertisement published on Nov. 26, 1759 in the newspaper The New York-Mercury. “Sadly, it is a runaway slave ad.”

ON THE MENU

Why was it important for the British colony of New York, an independent state, to set aside an official date? Colonists needed a morale booster, a respite from news of the ongoing Seven Years’ War. When the news that Quebec had fallen reached New York City, it was seen as one of the great victories of the conflict, giving the colonists reason to celebrate.

The settlers of all 13 colonies, including New York, were also enjoying a robust economy, so an official holiday gave them the chance to give thanks. One observer wrote that by the 1770s, the general standard of living in the colonies was the highest in the world.

A 2018 Newsday article reported on how the Universal Gazeteer, published in Dublin, described the Long Island of 1759: “The island principally produces British and Indian corn, beef, pork, fish, etc., which they send to the sugar colonies,…they also have a whale fishery, sending the oil and bone to England, in exchange for cloths and furniture. Their other fisheries here are very considerable.’’

Those fisheries provided different types of seafood that were likely on the menu at the 1759 feast, along with fruit from local apple orchards, and, of course, oysters. The observance also included a special sermon given by a minister.

HISTORIANS’ NIGHTMARE

While Weekes’ diary has survived as the earliest known mention of Thanksgiving in New York State, so many proclamations of a so-called “official” holiday were issued — throughout the nation as well as in New York State — that they could confuse even the nosiest historian. History buffs who have gone sniffing around undisturbed, dusty archive drawers have found enough to keep them awake at night. Starting in October 1621 with the Pilgrims’ three-day feast in Plymouth, Mass., multiple proclamations were made. Between 1623 and 1775, at least six Thanksgiving holiday observances were proclaimed in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and other colonies.

After Weekes died in 1772, his family deeded his documents to the museum, which gave history detectives the proof they needed to rewrite history.

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.