New book captures horrific migrant camp culture

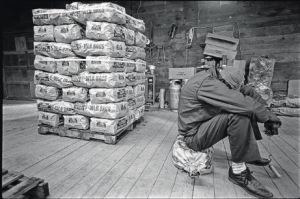

(Photos courtesy of the Lynn Johnson Collection, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries)

When author Mark Torres embarked on writing Long Island Migrant Labor Camps: Dust For Blood back in 2019, he was unaware he’d be researching a culture likened to a 20th Century version of slavery. Starting in 1943 and for the next five decades, farmers on the East End of Long Island used seasonal migrant workers to harvest potatoes, a crop that accounted for 80 percent of all the farming done on Long Island according to www.longisland.com. But the manpower used to harvest all this food came on the backs of low-income workers shipped in from the Deep South by unscrupulous camp operators who lured their victims with promises of good wages and decent housing. These migrants instead wound up as cogs in system of modern-day indentured servitude.

“Workers were told they could earn $47 a week but would later find out they would have to pay out $40 for costs,” Torres explained. “A lot of the workers didn’t have cash, so everything was on credit. They’d have to trust in the veracity of the crew leader, who always lied and made changes. Workers were lucky if they broke even at the end of the season. Most often, they were in debt when they left. They continued on to the next stop with the crew leader in the hopes of trying to get out of the red.”

In the bulk period of 1958, there were 134 registered camps and by 1960, roughly 4,500 workers were coming to the East End to do stoop work, the hard labor require to manually plant, cultivate and harvest crops. Living conditions were deplorable, with workers charged daily rent and crammed into crowded shacks that lacked heat and oftentimes plumbing. Crew chiefs took a cut of each worker’s pay and migrants were also charged fees for blankets, board and round-trip rides to the fields. Meals were eaten at an on-site eatery where food was liberally price gouged. With workers making roughly $10.80 for an eight-hour workday, debt was easy to slide into, particularly if machinery broke down since pay ceased while repairs were made despite daily expenses continuing to accrue. This stark reality was reinforced once all expenses had been deducted directly from their paychecks. Alcoholism was rampant, violence not uncommon and a lack of enforced safety standards meant many workers died in shack fires caused by accidentally overturned kerosene heaters.

In the bulk period of 1958, there were 134 registered camps and by 1960, roughly 4,500 workers were coming to the East End to do stoop work, the hard labor require to manually plant, cultivate and harvest crops. Living conditions were deplorable, with workers charged daily rent and crammed into crowded shacks that lacked heat and oftentimes plumbing. Crew chiefs took a cut of each worker’s pay and migrants were also charged fees for blankets, board and round-trip rides to the fields. Meals were eaten at an on-site eatery where food was liberally price gouged. With workers making roughly $10.80 for an eight-hour workday, debt was easy to slide into, particularly if machinery broke down since pay ceased while repairs were made despite daily expenses continuing to accrue. This stark reality was reinforced once all expenses had been deducted directly from their paychecks. Alcoholism was rampant, violence not uncommon and a lack of enforced safety standards meant many workers died in shack fires caused by accidentally overturned kerosene heaters.

As a labor lawyer for Teamsters Local 810 in Long Island City, Torres felt a duty to tell this story dating back to 2015 when he learned about their existence while writing his debut novel A Stirring In the North Fork.

“This is my most important work because it’s meaningful, true history that’s been hidden for so many years,” he said. “This happened around 90 miles outside of New York City and the majority of New Yorkers hardly heard of this or the extent of it.”

(Photo courtesy of Mark Torres)

The Floral Park resident was surprised to find out no books had been written on this topic and he’d be heading into virgin territory. It became even more of a challenge when he sent an information request to the Suffolk County Department of Health and only received documents from 1980 up through the present day. The prior 40-year window was lost as records from that time period had been legally discarded as part of the department’s move from Riverhead to Hauppauge roughly two decades ago.

Torres was left to rely on more than 300 newspaper articles, government data and interviews. The latter proved to be particularly difficult to set up, given the amount of time that had passed.

“A major challenge in doing this research was how much of it was chasing ghosts and trying to find people you feel connected with in real time, even though it was 50 or 60 years earlier,” he said. “Then of course you find out they had passed on. That kept happening repeatedly throughout the research.”

A pair of documentaries, 1960’s Harvest of Shame and 1968’s What Harvest For the Reaper, were crucial pieces of source material for Torres. The latter, which focused exclusively on the Cutchogue Camp, captured the reprehensible conditions, overt racism and general indifference that allowed these camps to exist.

“You won’t find a more vital piece of information in existence that explains the system better than Reaper,” Torres said. “One quote in the film,‘The humiliation and the being without is as natural to the worker as the air he breathes’ made me realize I wasn’t going to just talk about the camps and conditions. I wanted to describe the psyche of these people, in the camps, the community and the first responders. It affected everyone.”

While West Coast farm workers had the likes of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to lead their movement, local advocates like the late Arthur Cullen Bryant were no match for powerful East End farming interests and indifferent politicians. A downturn in the agricultural industry eventually led to the decline in the demand for migrant workers and the need for labor camps. Torres still sees correlations between this past history and the present.

“The book covers another example of the health of industry being more paramount than the condition of people,” he said. “These things happen through time and that’s sadly what happened here.”

Mark Torres will be conducting a virtual lecture for the North Shore Historical Museum on Tuesday, May 25 at 7 p.m. The fee is $15 and participants will be emailed a zoom link on the day of event. Visit www.nshmgc.org or call 516-801-1191 for more information.