During dark times, Dr. Isma Chaudhry turns to poetry.

“We first endure, then pity, then embrace,” she says, recently reciting a poem from Alexander Pope.

While poetry provides Chaudhry with a moment of solace, an escape, it’s the final two words of that stanza that nowadays gives her special pause. In her case, she worries that if Muslim Americans embrace their current situation—one in which people from certain nations are barred from entering the United States and Islamophobia continues to take hold—then the long struggle to quash prejudice and misconceptions about her religion would be comprised, and tragically, in vain.

“My biggest thing is that I just hope that people just don’t get exhausted, that’s how hateful rhetoric wins,” she says.

She worries about the many Muslim immigrants who’ve come to the United States seeking a better life who may be dispirited by the current political climate.

Chaudhry’s apprehension is not misguided or imagined: Attendance has dropped at the Islamic Center of Long Island, where she serves as president, and donations are down, because worshippers have become leery about writing checks, she explains.

“We want people to come, we want people to feel secure,” Chaudhry says. “Every time there’s an executive order, attendance dips…people think they’ll be tracked, they’ll be targeted.”

“Fear,” she adds, “brings in paranoia.”

On Monday, President Donald Trump signed a new executive order banning for 90 days the issuance of visas to citizens of six Muslim-majority nations and for 120 days refugee resettlement in the United States. “Travel ban 2.0,” as its been called, is more limited than one issued in February, which was written so ambiguously that even people living in the United States legally were impacted. But that has done little to quell concerns of Muslim Americans and immigrant communities. The Trump administration issued the latest ban incarnation after an appeals court in San Francisco declined to reinstate the previous order, which had been halted by lower court in Washington State.

The new order, which goes into effect March 16, makes it explicit that people with legal documentation not be impacted, and that waivers, in some cases, may be applied. It also omits language from the original order granting religious minorities entry into the country.

The fear Chaudhry talks about has been long-simmering. During the presidential campaign, then-candidate Trump called for a complete ban of non-U.S. Muslims from entering the country and toyed with the idea of a registry. As president, he’s signed the aforementioned executive orders and is reportedly considering exclusively focusing a Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) program on Islamic terrorism. Such a move would be a break from the current program that also considers right-wing violence, which has claimed half as many lives as jihadist attacks in since 9/11, but evokes little outrage.

Under President Obama, the CVE program generated mixed reviews. Some Muslims applauded the administration for being inclusive, while several advocacy and rights groups expressed concern that CVE would sow distrust because community members were being deputized to report extremist behavior, if any existed at all.

Taken together, the various policies being put forth by the administration in the name of national security has put many people on edge. The new ban has not eased those tensions.

“This was expected, so nobody was in a fool’s paradise that there was not going to be a follow-up,” Chaudhry tells the Press. “The community, we’re all very disturbed, first off, at the intent of this order.”

Rather than have Congress pass legislation curtailing immigration, the White House has instead issued presidential actions, which the administration argues is well within the powers of Trump’s office.

The administration cites the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which gives the president authority to suspend entry “of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.” Included in the order is an argument on national security grounds, noting that the six listed nations “present heightened threats” and recalling two episodes in which people who emigrated to the United States were arrested on terror-related charges—including one episode, ironically, of two men from Iraq, a country no longer impacted by the restrictions.

When lawyers for the administration defended the first order before an appeals court in San Francisco last month, they argued that border protection measures instituted by the president are “unreviewable,” to which the court said “runs contrary” to democracy.

State attorneys general in Washington and Minnesota successfully challenged the first order, largely because they could prove standing.

The new order was written to withstand judicial scrutiny and limit those who can claim injury. Some states are undeterred: Hawaii became the first state in the country to challenge the new ban and New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman said he’d join Washington State in a separate suit challenging the most recent order.

“President Trump’s latest executive order is a Muslim Ban by another name, imposing policies and protocols that once again violate the Equal Protection Clause and Establishment Clause of the United States Constitution,” Schneiderman said.

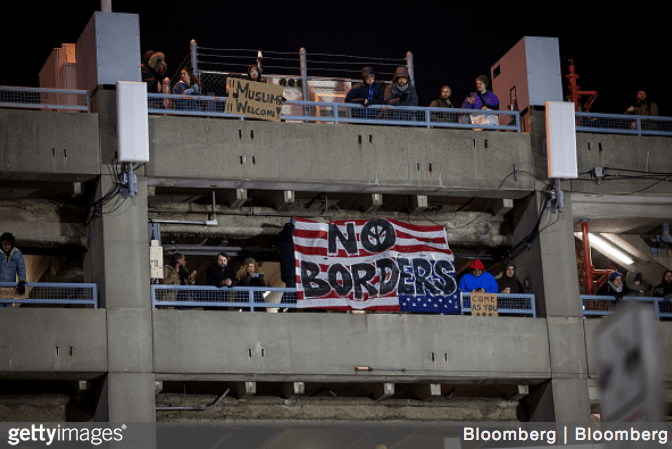

The signing of the first order almost immediately sparked outrage. Also, civil rights groups wasted little time taking the administration to court, scoring a quick victory at Brooklyn federal court, where a judge put a hold on deportations.

Alireza Hedayati, an attorney from Roslyn, used the resources of his firm’s office to assist immigrants who had been impacted. He has held a seminar in Little Neck with people inquiring about the legality of the order, the status of green card holders, and how far border agents could go when questioning travelers. Even after the first ban was frozen, people continued to call his office with questions, he said.

Hedayati, who sits on the board of the Long Island-based Iranian American Society of New York, questioned the logic behind the earlier ban, arguing that many Iranians build successful lives and work in white-collar industries.

“Everybody wants to be safe here,” he said after the first ban was issued. “How are you going to be less safe from people that are here working in a hospital?”

Long Island is home to the second-largest population of Iranians in the country, behind only Los Angeles. The community on LI includes Jewish Iranians, many of whom fled during the Iranian Revolution in 1978. America’s long and contentious relationship with the country, which is jockeying for power in the Middle East with rival Saudi Arabia, has complicated Americans’ views of Iran.

“I never viewed the Iranian perception as negative,” Shamila Dilmaghani of Jericho said after the first order was signed. “I have a lot of pride to be Iranian-American. I’m surrounded, literally, by doctors, lawyers, engineers…the circle I am surrounded by—and it is a tight-knit community—everyone’s successful. This is why this is so shocking.”

“They’re very loving and peaceful people, and they want to have a relationship with the West,” she said of Iranians. “And isolation is not the way.”

Of the countries listed, Iran has been singled out the most by the new administration, which is critical of the Obama-era Iran nuclear deal. After Iran conducted a missile test, Michael Flynn, Trump’s short-lived national security adviser, publicly said Iran was “on notice.”

Since 9/11, no one from the listed countries has committed a successful terror attack on U.S. soil, researchers have found. As of 2015, citizens of all six countries were prohibited to travel to the United States without a visa under a new law passed by Congress. The State Department has designated three of the countries—Iran, Syria and Sudan—as state sponsors of terrorism.

For those already in America, the ban is seen as provoking additional anti-immigrant sentiment.

Dr. Yousuf Syed, trustee of The Selden Mosque, believes the best way for the government to defeat radical ideology is by building trust with existing Muslim communities.

“To stop immigration is not a good thing,” Syed tells the Press. “A Muslim ban is divisive, immoral, and undermines our American values. It does not make us safer, in my opinion.”

Chaudhry says she already notices the consequences of the ban. Aside from a noticeable drop in mosque attendance, she’s also had a difficult time finding Muslims willing to speak at interfaith events. As a result, Chaudhry has had to fill that void.

“When you stop fighting for your own rights, or when you’re afraid to criticize the policies of the state, that is something which won’t take you to a good place,” she says.