“Uncomfortable. Impossible. My chest hurts,” says Vincent Pepe, 10, pointing to his t-shirt where he feels his heart rate accelerating. He won’t make eye contact. He doesn’t like talking about the state tests he took last year.

“There wasn’t enough time,” he says. “It makes you quit.”

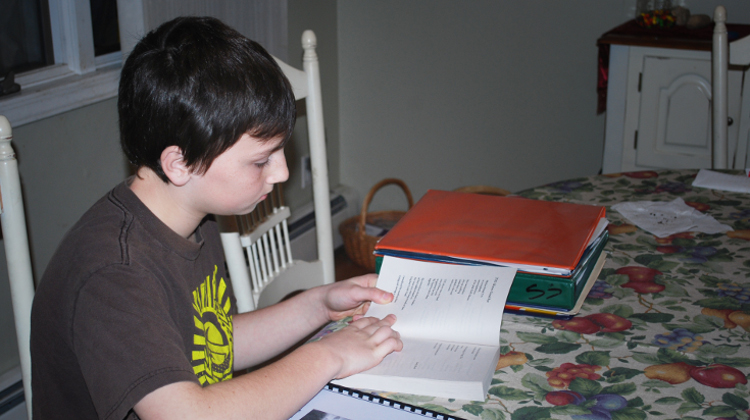

His older brother Ryan, 13, looks up from under a pile of homework. Ryan has served as Vincent’s protector since he was born. But Ryan can’t protect him from everything.

Neither will be taking the state tests this year. And they’re not alone.

A battle is being waged in New York State with Long Island on the front lines. The warriors come armed with manila folders of research on topics such as Common Core, data-mining and a billion-dollar company named Pearson. They have bags under their eyes from long, weary nights in front of sometimes-incomprehensible homework. The battlegrounds are the classrooms, the kitchen table, and auditoriums packed with parents and teachers who are demanding a three-year moratorium on high-stakes testing, but will settle for the resignation of New York State (NYS) Commissioner of Education John B. King, Jr. and the head of Gov. Andrew Cuomo. They are an army formed on Facebook, with groups informed by a national movement but concentrated right here, mobilized and motivated by the stress of their children. Their vow is to defeat Common Core, the educational reform so extreme that kids are mutilating themselves in response to the psychological stress that experts are calling “Common Core Syndrome.”

The Common Core State Standards, created by the National Governor’s Association and the Council of State School Officers, purport to make American students globally competitive, with skills that promise college and career readiness, with standardized testing in English Language Arts and math starting at grade three. Its dual purpose is also to hold teachers accountable for students’ achievement, using high-stakes test scores to determine teacher effectiveness. The financial incentive for states to adopt this reform is considerable; New York received $700 million alone.

Yet the parents and teachers opposing the program say they are fighting for something beyond a price tag: the minds of their children and students.

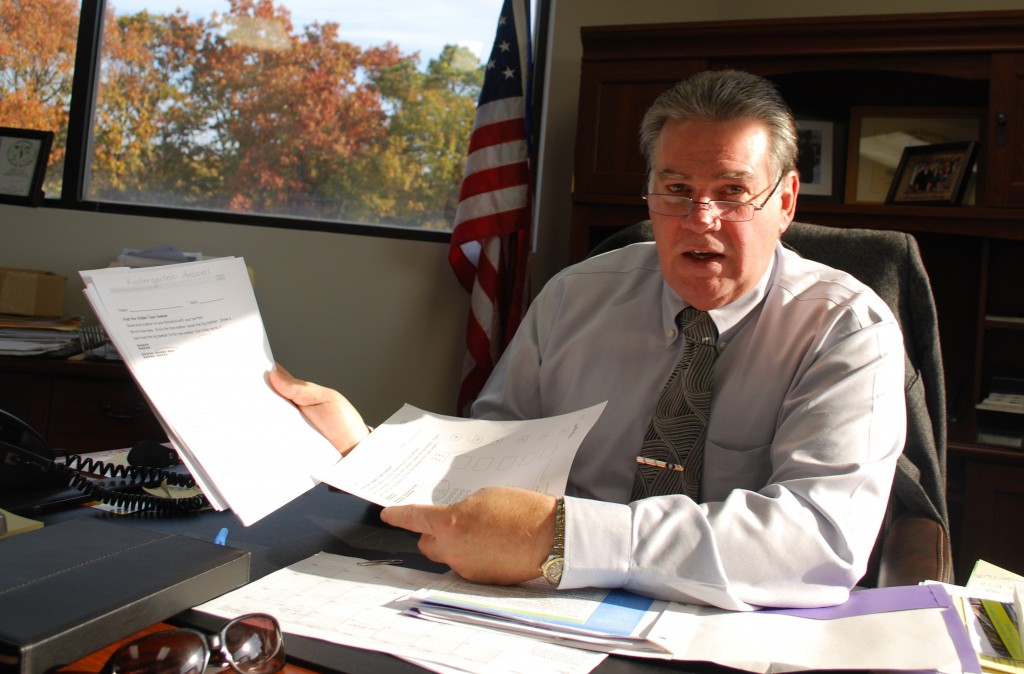

More than 18,000 Long Islanders have signed a petition put forth by NYS Assemb. Al Graf (R-Holbrook), who, acting as a self-described “vessel of the mothers,” has staked his political career on fixing New York schools, effectively removing what many feel is a one-size-fits-all approach to education that fails the individual needs of children. Each signature generates e-mail directly to Cuomo’s office. Opponents are also curious about Pearson, a company awarded a $32 million contract by NYS for testing services last year in addition to “Race to the Top” federal funding to provide textbook and teaching materials.

Parents and teachers have begun a groundswell of opposition on the central concern that Common Core is hurting their children through its undue reliance on extensive testing and incomprehensible homework that has brought stress and anxiety to their kids.

“The commissioner told us that these tests are predictive of college success,” says Dr. Joe Rella, superintendent of Comsewogue School District. “How am I gonna tell a third grader, ‘Don’t bother showing up for the next nine years because you’re not college material?’”

But the powers that be in government from President Barack Obama on down, support this education reform—financed with more than $4 billion of “Race to the Top” funds as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

“I…want to congratulate @NYGovCuomo &…NY for having the courage to raise your standards for teaching & learning,” Obama tweeted Oct. 25.

After all, the president—a father with two young daughters himself—had to have good intentions.

GOOD INTENTIONS

During Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, he vowed to take a hard look at the nation’s public education system and make some much-needed changes. Community colleges reported that incoming freshmen increasingly needed remedial courses to bring them up to college level, at a cost to both schools and parents. The reform tried to reverse-engineer from the college level on down to kindergarten what students are expected to learn, both cognitively and developmentally, to an unprecedented degree.

“We all share the same common goal: that every student in New York graduates college- and career-ready,” New York State Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl H. Tisch said in a prepared statement on New York’s National Assessment of Educational Progress results, which, he added, “confirm what we already know: Our students are not where they should be.”

According to the state student exams, only 35 percent are college- and career-ready.

“It’s just more evidence that New York needs to stay on this road,” says King, who has become a lightning rod for criticism of the plan.

Perhaps no one is more aware of how educational trends come and go than Dr. Arnold Dodge, a professor of education at Long Island University Post and chair of its department of educational leadership and administration. For 44 years, Dodge has served various roles in education, from teacher to superintendent of East Rockaway schools. This time, he says, is different.

“In 1983, they issued a report called A Nation at Risk in which they say, ‘We are losing the education wars,’” recalls Dodge. “The famous line is, ‘If this were a battlefield, we’d have to declare war.’ Fast-forward to 2000 and the idiot President George Bush comes in and says, ‘Is our children learning?’ Literally. He said that.

“And then he, along with his cronies and with support of the Congress, in 2001-2 creates No Child Left Behind legislation. He says, ‘So what if you have to teach to the test? That’s what we should be doing.’ So I’m at a national conference in 2002, and I see what’s coming: a tidal wave.”

The tidal wave came in the form of state standards that were tied to unfunded mandates. At the time, Arne Duncan, then the chief of Chicago’s public schools, called No Child Left Behind a “train wreck.” Yet Race to the Top and Common Core, Obama’s response to Bush’s initiative, appear to be extensions of the same ideals and framework. At the American Education Research Association conference in California earlier this year, where Duncan, now Obama’s secretary of education, was a keynote speaker, Dodge had the opportunity to address this inconsistency.

“I said, ‘Let me ask you a question, Secretary Duncan: Have you even read your own law? Do you understand that you’re suffocating us? That there’s no oxygen left for the children? That the tests have all the meaning and everything else has no meaning? I’m going to ask you a question: Will you declare a moratorium until we get this right?’”

Parents, teachers, and most recently, a collection of principals, have put forth the question of the moratorium, saying implementation of this contentious reform was too hasty and questioning why both the mathematician and the literacy experts on the Common Core validation committee refused to sign off on the new standards. They want the program halted, effective immediately.

Laura Spencer, a Smithtown schoolteacher, expressed her opinion directly to the state’s education commission at a public forum last month at Ward Melville High School in Suffolk.

“Teachers and administrators have been flexible working with the demands from the state,” said Spencer. “Commissioner King, we are asking you to be flexible. Will you consider a three-year moratorium on high stakes testing? When making your decision, consider the fifth grade special education child screaming, ‘I am stupid!’ for one hundred and eighty minutes during just one day of the math state assessment. I know this, because I was a proctor. With a three-year moratorium, we can work together to get it right for our students.”

But the answer from above is that New York will press on, full-steam ahead.

To many, this means war.

THE MOMMIES REVOLT

The Pepe brothers sit at their dining room table, their books and binders spread out over the flowered tablecloth. It won’t be long before Ryan begins to plead with his mother to skip school tomorrow.

“I hate waking up on Mondays,” says the eighth-grader. “Because I know I have another week of school to get through.”

His mom says that before Common Core was implemented, Ryan was raring to go to school. Now, mornings are an ordeal.

Ryan particularly dislikes the benchmark tests students must take in the beginning of the school. This is compared with the same test at the end of the year, where learning growth will be calculated.

“I could handle the social studies one, because if you know stuff about social studies, then you could get some of the questions right,” he explains. “But for the science one, there’s literally no way of knowing half the stuff that’s on there. They’re giving you a test on everything you’re going to learn throughout the year, except you don’t know any of it yet. So most people—all people—fail it.”

Failing is especially hard on kids like Ryan, a high achiever who has never failed a test before. It’s even tougher on kids like his brother Vincent, who has autism.

“People on the low end of Asperger’s cannot tolerate being tricked,” says Mary Calamia, a clinical social worker. “They don’t accept failure well. And they need to please. They take it very personally. They don’t understand.”

“My heart feels upset,” Vincent says. “I was afraid that I would get in trouble if I asked to opt-out of the state test. I was uncomfortable.”

His reaction was similar to that of the daughter of a teacher in Westchester.

“My oldest is very bright,” says Michele, who asked that her last name be omitted from this story due to fears of retaliation from school officials. “Since last year in fourth grade, she would come home and would just be crying. A lot of it was the inferential thinking. Reading between the lines. And even though she’s bright, that part of her brain isn’t completely mature yet. That’s where that shift starts to happen—that upper-level, critical thinking, which really doesn’t develop in most kids until they go to junior high school. You can’t force that. So night after night, she’s spending over two hours on it.

She’s perseverating on it. She’s like, ‘Oh my God! I’m so dumb, I just don’t get it.’”

On Nov. 13, protesters lined Old Town Road carrying signs and shouting for “revolution” outside of Ward Melville High School. The ground was frozen with the year’s first snowfall but, undeterred, parents swarmed the school, lining up hours before the doors opened for a forum where Education Commissioner King and Regents Chancellor Tisch made their first LI stop on their re-instated “listening tour,” which had been postponed after protestors shouted King down in Poughkeepsie.

The 900-seat auditorium was filled to capacity with more than 400 people spilling over into the cafeteria, where it was streamed live. Many wore green glow bracelets, an homage to the “Lace to the Top” movement in which children wear green shoelaces to bring attention to the opt-out movement sparked by Long Islander Jeannette Deutermann.

Deutermann, a mom from Bellmore, has been consumed with creating templates for each type of assessment so parents like Meghan O’Hara can notify their school districts of their child’s intention to refuse testing. The reasons O’Hara listed to opt-out were numerous: “The hours of instructional time lost to testing and prepping for the test; linking it to an invalid curriculum lacking empirical evidence therefore invalidating the results, setting kids up to fail; the tests serving no diagnostic purpose; using a child’s score to rate a teacher’s performance.”

Parents want the governor, the commissioner, and the chancellor to acknowledge the emotional toll Common Core is taking on their children.

“This year, from day one, I sent [my son Christian] into school all happy and excited, like a helium balloon,” laments GiGi Guiliano of East Islip. “And then he came out, all deflated. By the end of the first week, he says, ‘I am never gonna smile again.’”

Jack Lewis, a ninth-grader from Plainview, fells the same way.

“It’s taken all the fun out of the actual learning,” he says. “In English now, you have to read these articles. You can only do one paragraph per period. My teacher said she wants to move ahead, but I think she’s scared that she’ll get fired.”

He ruffles through his backpack to produce an article he was reading in class. “This one is about doctor-assisted suicide.”

Allie Gordon’s voice shook as she addressed the commissioner and the chancellor at Ward Melville High School.

“Recently, my 10-year-old daughter asked me what it would take for me to let her stay home from school forever,” she said. “Not tomorrow. Not next week. Forever. She said: ‘I’m too stupid to do that math.’ Your child is broken in spirit when they have lost their confidence and internalized words like stupid. That damage is not erased easily.”

Even school administrators themselves oppose the state tests tied to Common Core, alleging they were designed for children to fail.

“The problem with these tests [is that] our kids believe everything we tell them,” says Rella, the Comsewogue School District superintendent. “They don’t know it’s a rigged game. They don’t know that long before they sat down to put pencil to bubble sheet last April, it was already a done deal that only 30 percent would pass. I got two memos—one from the deputy commissioner, one from the commissioner. We don’t expect more than 30 to 35 percent to pass this test. And then—as if that weren’t enough—after the testing was all done, that’s when the passing score was set.

“This isn’t a secret,” he says. “And then—imagine! Thirty percent of the kids passed statewide!”

Principals statewide are also taking a stand. An open letter to parents from nine principals authored on Nov. 16 and signed by more than 3,100 principals of New York schools reads: “We know that many children cried during or after testing, and others vomited or lost control of their bowels or bladders. Under current conditions, we fear that the hasty implementation of unpiloted assessments will continue to cause more harm than good. Please work with us to preserve a healthy learning environment for our children and to protect all of the unique varieties of intelligence that are not reducible to scores on standardized tests.”

Calamia, the social worker, says that the influx of children who have come to her seeking therapy for stress and anxiety has increased exponentially with the implementation of Common Core. It was the same thing, repeatedly: self-mutilation, such as the 8-year-old child who picks the skin off of his face.

“It was constantly about: ‘I can’t take the workload. I feel stupid. I can’t take the pressure. It’s too much,’” she says. “All I was hearing about was the academics. I heard about a little boy in first grade who, when he does his homework, he scratches down his face. He has claw-marks down his face.”

Calamia declares Common Core standards developmentally inappropriate.

“There’s a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, where all abstract thought comes from,” she explains. “And that is developing until age 24. It isn’t fully developed even in adolescence. The curriculum right now is like asking a fish to fly. And try as it might to grow wings, that fish is going to be ashamed of its gills. I heard of a young lady who carved the word ‘stupid’ into her wrist after she got her math assessments back.”

The detrimental impact the new regime is having on some children’s health is so rampant that it has resulted in what some call a new psychological condition.

“There is now a ‘Common Core Syndrome,’” Port Jefferson Station Teachers Association President Beth Dimino told Commissioner King at Ward Melville’s town-hall meeting. “Psychologists are now diagnosing our children with a syndrome directly related to work they are doing in the classroom. I tell you, Mr. King—because you’ve awoken the mommies, you’re in trouble.”

Education Secretary Arne Duncan dismissed these concerns, telling a group of state school superintendents at Richmond, Va., on Nov 15: “It’s fascinating to me that some of the pushback is coming from, sort of, white suburban moms who—all of a sudden—their child isn’t as brilliant as they thought they were.”

To the mothers and teachers witnessing Common Core’s repercussions on children and students firsthand, the demeaning comment illustrates just how disconnected government administrators are to the reality in the classroom.

The fact is, the children of the white suburban moms Duncan mentioned had been doing just fine. LI’s graduation rates have significantly exceeded those of the rest of the state. The average rate on LI for the 2011-12 school year was 87 percent compared to 74 percent statewide.

Beyond white suburbia, the educational system has failed the nation’s children—with a direct correlation between poverty and failing schools.

“It has to do with families and socioeconomic statuses,” says Michele, the Westchester teacher. “It goes so far beyond the walls of the school. We’re trying to put a Band-Aid on something that has been happening since the child was in the uterus.”

“It’s about poverty,” agrees Dodge, the LIU professor. “I heard Bill Gates say, ‘Look at the scores in Shanghai! How come we can’t be like Shanghai?’ I’ve been to Shanghai. It’s Beverly Hills on the water.

“You can’t compare the United States to Shanghai when our scores include poverty-stricken areas where people have nothing,” he says. “It’s like comparing Scarsdale to sub-Saharan Africa. Without the filter of poverty and without the beleaguered communities that you’re putting out there and disaggregating the data, you’ve got fraud. And that’s because you’re serving a political agenda and not the truth.”

IN THE CROSSHAIRS

Rella, the Comsewogue superintendent, became a rock star of the anti-Common Core movement when he published a letter to state senators questioning the validity of the tests and requesting reform.

“If not,” he wrote, “then I request on behalf of our residents—your constituents—you initiate proceedings to have me removed as superintendent.”

Rella walked out to hearty applause at a forum at a New Hyde Park Elks Lodge in October, where parents gathered looking for answers and support.

To demonstrate the program’s toll on students, Rella described an imaginary charter school, modeled after the Common Core standards, which would include “high levels of rigor” and “a totally test-centered approach to teaching. And as a result of our rigorous, gritty approach, students will experience increased anxiety, stress, behavioral problems, sleep deprivation, respiratory issues, self-destructive and self-abusive behaviors.”

He paused.

“This would be kinda funny if it weren’t so true,” he said. “It would be funny if children all over the state weren’t being hurt, if their teachers were not turning themselves inside-out trying to protect them. It would indeed be funny if it wasn’t so tragic.”

His testimony illuminates the quandary teachers are in. Many teachers fear for their livelihoods, as the tests account for 40 percent of their Annual Professional Performance Review evaluations. If enough students don’t pass the tests two years in a row, even tenured teachers can lose their jobs.

Carol Burris, principal of South Side High School in Rockville Centre, who was named 2010 Outstanding Educator by the School Administrators’ Association of New York State, was originally a champion of Common Core, co-authoring the book Opening the Common Core. Her blog from The Washington Post in 2012 demonstrates how Burris’ optimism soon soured.

“I confess that I was naïve,” she wrote. “I should have known in an age in which standardized tests direct teaching and learning, that the standards themselves would quickly become operationalized by tests. Testing, coupled with the evaluation of teachers by scores, is driving its implementation. The promise of the Common Core is dying and teaching and learning are being distorted.”

King asserts that “curriculum decisions are local decisions,” but teachers fear that with the tests determining their job security, there is too much at stake to retain local control of their classrooms. Instead, they are compelled not to stray too far from the state-supplied modules on which the tests will be based.

Melissa McMullen, a Port Jefferson Station middle school teacher, told King: “We can’t say that curriculum stands alone when teachers are held accountable to a state test. That doesn’t cut it.”

“The only purpose of this testing,” blasts Rella, “is to humiliate and embarrass teachers.”

Craig Charvat, a history teacher from Center Moriches, has offered himself up as a sacrificial lamb to bring attention to what he calls a “fraudulent” teacher evaluation process. Muscular with a strong physical presence, he recently described his ordeal, sitting in a coffee shop in Patchogue, his bravado quickly giving way to emotion, tears welling up in his eyes.

He spoke of benchmark exams that were used to measure the growth of learning across five subjects in his school. Teachers were told that the tests would take between 42 to 45 minutes, but classroom periods only run 40.

“That was the first thing that got my attention,” he said.

More red flags went up when Charvat noticed that not only was the history test for which one-fifth of his assessment was based not given in the spring, but that the answer sheets did not match up with the tests that were given. He brought the matter to his principal and superintendent, but his concerns were dismissed. So he went public.

“I made peace with the fact that I could lose my job,” he said. “I love teaching. It’s my dream job. But the way they’re implementing these tests—it’s fraud.”

He says that he isn’t adverse to accountability, but he refuses to comply with a system corrupted by shoddy implementation of tests and mismanagement, resulting in an “ineffective” rating, a badge he wears proudly to call attention to a failing system.

“You do accountability with strong leaders, who understand protocol, who are fair with people but also understand what good teaching is,” says LIU’s Dodge. “As a leader, you should always be looking for student engagement. It’s more important than achievement.

“It’s a false dichotomy to say those of us who are against the tests are against accountability,” he adds. “The most accountability I want is accountability to children’s well-being, and that’s what we don’t have. Because I feel accountable for all the children of New York State.”

“The real agenda,” alleges Rella, “is to so shake confidence in public education and destroy it. Withhold funding, pile on unfunded mandate after unfunded mandate, make it impossible for public schools to get the job done. Once that happens, well, then the solution is, ‘Close them down. We need private schools. Privatize for profit.’ It’s not a big jump.”

Dodge concurs.

“The biggest pusher of that is Pearson…a huge multi-billion-dollar international company,” he says. “Obama knows that the economy is job number-one. It’s a multi-billion-dollar industry just waiting.”

Critics allege that companies such as Pearson, whose North American headquarters are in Upper Saddle River, N.J., blur the lines between public education and private profit. Most of the creative work on the Common Core State Standards was contracted to Achieve Inc., which received millions in funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The foundation also gave a $100-million grant to Atlanta-based data-storage company inBloom, which collects and stores students’ information, including mental health records and behavioral issues, in a database in “the cloud.”

“We are 100-percent committed to data protection privacy,” says Education Commissioner King. “inBloom maintains all data in encrypted form. We believe that our project with inBloom is actually a step in the direction of raising standards in regard to privacy and protection.”

Parents’ fears of school data thefts were bolstered on Nov. 22 when an accused teenage hacker was arrested for allegedly breaking into the Sachem School District’s records and posting thousands of private documents on the Internet.

But, despite parents’ anger spilling into the streets over Common Core, there’s a way back, Dodge insists.

“There’s an expression that we use in the leadership class called, ‘The Escalation of Commitment,’ which means: ‘I made a mistake. And just to show you that I know that I’m innocent but I’m not going to announce it, I’ll go down and I’ll make even more of a mistake.’ It’s time for politicians and leaders everywhere to stop the hubris, take a deep breath, and say, ‘We made a mistake.’”

An increasing number of parents, teachers and students across LI are counting on it.

“I feel like everything we’re learning about in school is becoming dark,” says Ryan Pepe.

“The Great Depression,” his brother Vincent piped up. “That’s me: I’m great. And I’m depressed.”