Photographer and former entertainment attorney Xiomáro has released a new book of street photography capturing the people, politics and overlooked details of New York City — a project he never expected to undertake when he first picked up a camera during his recovery from cancer two decades ago.

The Roslyn Heights native, who now lives in Ramsey, N.J., is best known for his work documenting national parks and historic sites across the Northeast and beyond.

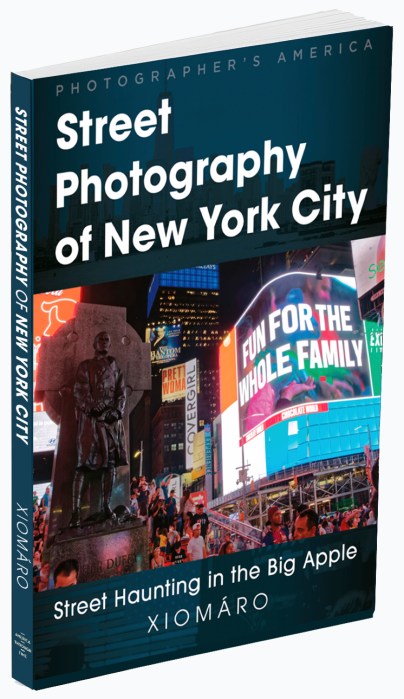

But the release of his new book, “Street Photography of New York City: Street Haunting in the Big Apple,” marks a shift in focus, one motivated by both artistic growth and uncertainty about the future of federal arts funding.

Xiomáro’s journey to photography was neither direct nor traditional.

After years spent balancing corporate litigation with creative ambitions, his trajectory changed abruptly when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in his early 40s. The disease was caught early, but the six-month wait for surgery forced a profound reckoning.

“I didn’t know if I was going to live or die,” he said. “It got me thinking that maybe it was time to pursue my own creativity instead of helping everyone else pursue theirs.”

During his recovery, he found solace in wandering national parks with a small digital camera.

He began displaying the images at his solo music gigs, and the photographs sold sometimes better than the CDs.

That early encouragement led him to apply for an artist-in-residence position at Weir Farm National Historical Park in Connecticut. He was accepted, lived on site for a month and produced a collection that drew national attention and set his career on a new path.

Though he built a reputation as a national-park photographer, Xiomáro turned to street photography out of necessity.

While working long hours at a Manhattan law firm, he needed a way to stay sharp between major assignments. The walk between Penn Station and his office became a twice-daily training ground.

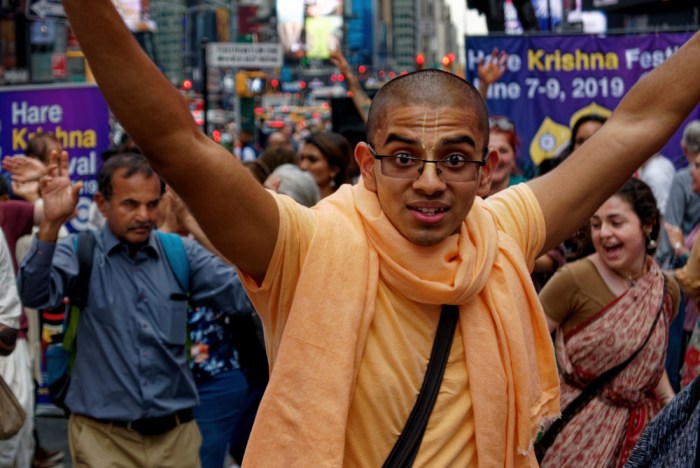

Unlike landscape work, street photography offered no control, only motion, noise and fleeting moments.

“It improved me as a photographer,” he said. “Everything is moving. Everything is fast. You have to respond instantly.”

His new book organizes those images into three chapters: portraits of everyday New Yorkers; signs and messages — from political protests to handwritten wishes left for the New Year’s Eve ball drop; and the often-ignored architectural details that hide in plain sight above city sidewalks.

Each photograph is accompanied by an essay-style caption, turning the book into what he calls “a book within a book,” blending image, philosophy and social commentary.

His publisher, Sutton Publishing in England, has already contracted him for two more books.

The next, “Street Photography of the Wildwoods,” will be released in March and explores a New Jersey shore town whose glossy 1950s nostalgia contrasts sharply with its contemporary political extremism and cultural contradictions.

The third, due in 2027, returns to New York City with a more abstract approach, including dramatic shadows, motion-blurred figures and surreal reflections captured in windows, puddles and metal surfaces.

Even as his street-photography career grows, Xiomáro continues his national park work — though he worries that federal shutdowns, reduced staffing and shrinking budgets could jeopardize future commissions.

His current assignment in Virginia, documenting Washington’s birthplace for the nation’s upcoming 250th anniversary, is expected to span several years.

Whatever direction his work takes, Xiomáro views his images the same way he sees the parks he photographs: as a form of preservation.

“When I’m long gone, these pictures will live on,” he said. “They’re part of our history — whether it’s a national park or a street corner in Manhattan.”