Black Hole Sun

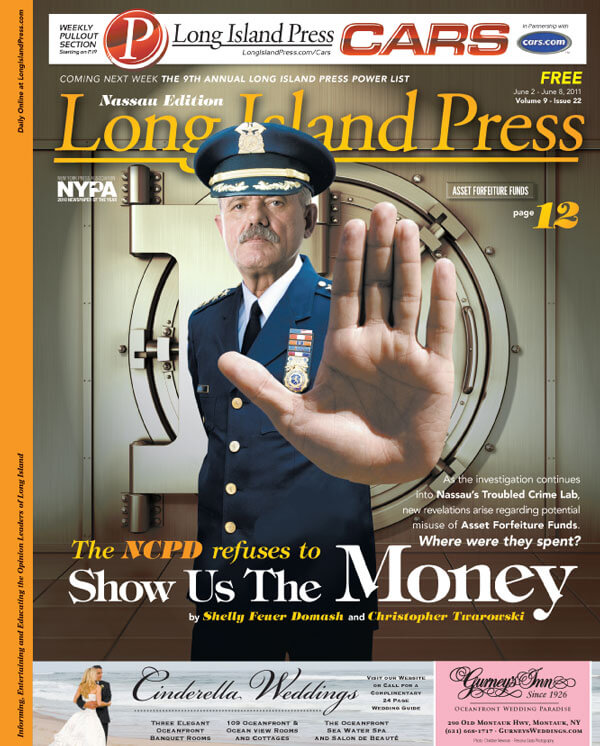

The Press’ first FOIL request to the NCPD seeking details about its forfeiture funds was filed on June 21, 2010, clearly stipulating for a list of “all projects paid for in the past five years by asset forfeiture funds. In addition…the amount of money that has been spent on each project. Also, how much has been taken in during the same period of time.”

Numerous phone calls and verbal requests by the Press followed, along with more written requests and eventually a petition to forward the unanswered requests to an appeals officer. Only one reply. On August 23, the Press was notified an answer would be available in approximately three weeks. No other communication or information on the unit was received from the department, despite another follow-up letter on Sept. 10.

According to Robert J. Freeman, the executive director of the New York State Committee on Open Government and a nationally recognized expert on open government issues, a local or state agency has five days to respond in some manner; it cannot simply ignore requests. If the requests are ignored, or the time has gone by with no response, an appeal can be filed, which must be answered in 10 days. If that time expires, then the petitioner must turn to the courts, a process that could entail an additional amount of time, he stresses—and cost taxpayers a bundle.

“Taxpayers are interested in this kind of situation because the court has the ability to award attorney fees that are payable by the government when an agency ignores a request for information,” he told the Press in March.

He concluded that Nassau’s actions were then in violation of state Freedom of Information Law regarding a timely response to FOIL requests. It’s now two months later.

“Even the police have an obligation to comply with the law,” he said.

The Press is not alone in its quest for NCPD transparency. Less than two weeks after the Press’ March 31 cover story discussing the NCPD’s noncompliance with open government laws, Long Island’s lone daily newspaper, Newsday, published an op-ed on its editorial page calling for exactly the same thing, pointing out that the Suffolk County Police Department readily opened its asset forfeiture books.

Yet whether the NCPD wants to release all the data requested by the Press is irrelevant. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), one of the lead federal agencies in administering the federal Asset Forfeiture Law, has released meticulous guidelines on the program calling for exactly that.

Ironically for Nassau, the protocols stress the importance of transparency in the funds’ use as a means of furthering its goal of thwarting crime through publicizing its efforts. According to the DOJ’s National Asset Forfeiture Strategic Plan 2008 – 2012, informing the public of the funds’ expenditures is a top priority:

“Publicize the benefits of asset forfeiture through the media,” it reads. “Create and distribute an asset forfeiture press packet for personnel who handle press releases and who are involved with asset forfeiture. Request that public relations offices include asset forfeiture in press releases on law enforcement operations that involve significant asset forfeiture activities. Post information on program participant public websites to provide general information.”

In contrast to NCPD’s secrecy regarding the funds, the DOJ calls on law enforcement agencies to be transparent:

“Issue an annual report on the accomplishments of the program,” it states. “Establish and communicate a process for collecting program statistics, successful cases, initiatives, news articles, and other media. Develop and publish a monthly report on program successes. Develop an annual report on program accomplishments… Release the annual report to the public.”

Finding details regarding expenditures can be an impossible task unless they are released to the media in accordance with the guidelines. Forfeiture money cannot be used for non-law enforcement purposes or by a non-law enforcement agency, according to policy guidelines—casting doubts on its legitimate use for upgrading the security system of Nassau’s Theodore Roosevelt Executive and Legislative Building in Mineola, a current proposal that has been put out to bid.

The National Code of Processional Conduct for Asset Forfeiture, developed by the DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section, states in its 10 “commandments” that “seizing entities retaining forfeited property for official law enforcement use shall ensure that the property is subject to internal controls, consistent with those applicable to property acquired through normal appropriations of that entity. Unless otherwise provided by law.” It also stipulates that forfeiture proceeds shall be maintained in a separate fund or account subject to appropriate accounting controls and shall avoid any appearance of impropriety in the sale or acquisition of forfeiture property.

The DOJ and Department of Treasury do no require itemized expenditure reports, therefore, without NCPD’s release of the information there is no way to actually document how much and where any seized funds were spent and how much collectively was taken in; no way for the public to know.

Mulvey had no explanation as to why the NCPD was holding up releasing information that was, under prior administrations, easily obtained.

“FOIL requests are answered by our legal bureau,” Mulvey recently told a Press reporter. “We get audited by the feds yearly—our operation is all above-board and I have 100 percent confidence in it. So, if there is information that we are duty-bound to release, then we should release it. I have no issue or problem with that.”

As for why the department still hasn’t responded to the Press FOIL requests, Mulvey insinuated perhaps there was confusion regarding their content.

“I don’t know specifically what [the Press] wrote,” he continued. “But I did hear from others that [the Press’] FOIL requests were poorly written, unclear, things along that nature…You should give a call to the deputy commissioner of police, tell him you spoke to me: William Flanagan.”

[A follow-up FOIL by the Press simply asked for a specific-numbered form.]

The former commissioner disputes the idea that asset forfeiture funds could have somehow been used to rectify the slew of problems existing within Nassau’s troubled crime lab, which was shut down in February by Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano at the behest of Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice following a scathing report by a national accreditation agency in November and its censure to probationary status last December.

Issues ranged from the mishandling, improper storage and safeguarding of evidence to non-calibrated equipment and instrumentation to nonexistent fire detection systems to a lack of annual proficiency testing or necessary degrees among examiners.

“Due to the high level of humidity in the controlled substances instrument room (water dripping from the ceiling), the logbooks for the GC/MSD #1 and the gas and liquid chromatographs have suffered water damage that has rendered pages to be illegible and entries are no longer visible,” states the report.

“You won’t find any issues there where they needed a microscope or they needed this piece of the equipment or that piece of equipment,” explains Mulvey. “We spent quite a bit of asset forfeiture money on sending those lab technicians to conferences to keep their certifications, to update their training, that kind of thing you can pay for with forfeiture funds, it’s not a normal budget item. But I’m not aware of an equipment request they had that was denied by us—and the audits from ASCLD/LAB [the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board] doesn’t cite faulty or inadequate equipment. It cites, unfortunately, sloppy oversight, it cites poor quality control, it cites some procedures that we were using that were outdated. But nothing in the area for them needing, you know, microscopes or test tubes and we weren’t able to pay for them.

“You can call the feds on that one,” he says, referring to his assertion the funds couldn’t have benefited the lab—where critically sensitive and important tests and analysis work on narcotics, fingerprints and blood was conducted; examinations that ultimately helped decide the fate of countless defendants and determine how much time, if any, they’d spend behind bars.

David Shapiro, an assistant professor of economics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, strongly disagrees, explaining that asset forfeiture funds could have been used for equipment.

“Of course they could have used that money,” he says, adding that guidelines specifically cover it under public safety and security procedures. “By definition you are enhancing the ability to get convictions and liberate the innocent,” he explains.

After the lab’s closure, District Attorney Rice ordered sample evidence in about 3,000 felony drug cases dating back to 2007 to be retested by Willow Grove, Penn.-based The National Medical Services (NMS) lab, which is also handling all new drug testing. A spokeswoman for Mangano put the tab for the retests as high as $500,000—to be paid for by asset forfeiture funds.

“Now retesting the drugs, based upon ASCLD/LAB, that’s not in any operating budget,” adds Mulvey. “So yes, we’re paying for the retests of the drugs with forfeiture funds. We’re not violating any protocol. This was something that was not foreseen.”

As John Jay’s Shapiro explains, however, paying for the retests with asset forfeiture funds doesn’t mean it won’t affect the taxpayer.

“They are using it as if it was found money, but actually it is supposed to be used to supplement general funds,” he says. “For example, they are an asset meant to reduce the burden on the taxpayer. Why blow it? It is not simply found money that they can say doesn’t come out of taxpayer funds. It should be used to defray other unexpected expenditures, instead of being used to pay for something they should have done right the first time.”