The scene plays out on television and movie screens time and time again.

Police chase a gleaming hotrod driven by a drug dealer through the streets—or maybe it’s a Lamborghini, pulled over for rocketing past a few officers on lunch break. They pop the trunk and discover a cache of cocaine and weapons. When they raid the dealer’s mansion, it’s loaded to the brim with fine art, a few more luxury sports cars and tinted-out SUVS…and vaults of more drugs, lots and lots of drugs.

Those vehicles, property, firearms and narcotics are seized, eventually sold at auction; and the proceeds given back to the police departments and other local, state and federal law enforcement agencies involved in the takedown and seizure. They’re known as asset forfeiture funds.

Simply put, the goal of the federal Asset Forfeiture Program, overseen by the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S Department of Treasury, administered by the U.S. Marshals Service with the participation of several other agencies, is to remove the tools of crime from criminals. Asset forfeiture deprives wrongdoers of their profits and recovers property that can be used to compensate victims and deter future crime. The funds are shared with state and local law enforcement agencies, providing a crucial revenue stream that can be utilized under strict provisions to purchase much-needed pieces of equipment not included in municipalities’ budgets. Examples include high-tech gear like hazardous material suits with ventilators, bought after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, marine patrol boats, or perhaps, even rehab a neglected crime lab.

Transparency is at the heart of the program, as publicizing such seizures and initiatives funded by them broadcast the message that crime does not pay. In the Department of Justice (DOJ)’s official guidelines agencies overseeing these critical funds are encouraged to employ the media as a primary outlet.

Not in Nassau.

Even though the Nassau County Police Department (NCPD) maintains its own active and prolific asset forfeiture bureau to handle such monies, obfuscation is the rule.

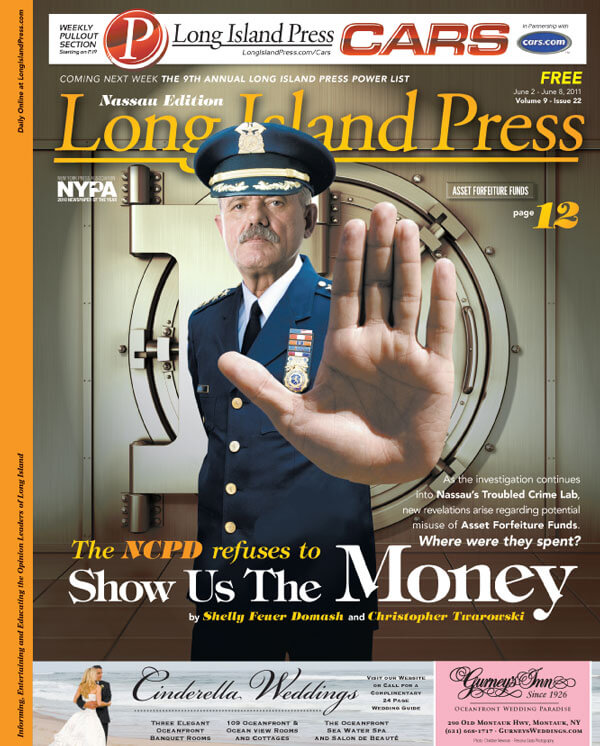

The NCPD has refused to fulfill a New York State (NYS) Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request filed by the Press last June (and followed up several times), seeking specific details including the exact amounts of these critical funds the department has taken in and distributed throughout the past several years. The department’s secrecy regarding these monies was first reported by the Press in a March 31 cover story [“Membership Has Its Privileges: Is NCPD Selling Preferential Treatment?”]. Its continued non-compliance with NYS Freedom of Information Law only further fuels questions regarding the validity—and legality—of its asset forfeiture expenditures, casting a critical light on current and former police responsible for overseeing the funds’ use, such as former Nassau Police Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey (who retired in April) and current Acting Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter.

[Krumpter contacted the Press approximately one hour before this story’s press time, but he was not able to provide any substantive information regarding the forfeiture funds and their disbursement by our deadline, other than sharing the total current account balance of $2,037,040. He said he would address all the Press’ requests and allow the Press access to all the requested information as soon as possible, and he defended his department’s transparency. “We are 100 percent transparent,” stressed Krumpter. “We have never, never—never—been accused of not cooperating with the media.”]

The asset forfeiture issue comes at a precarious time for the 86-year-old department, currently in the throes of a still-unfolding scandal that led to the much-publicized closure of its crime lab—the subject of an intense ongoing investigation by New York State Inspector General Ellen Biben. One thing’s for certain regarding Nassau’s handling of the funds: Major changes were made to its internal oversight process during the administration of former Commissioner Mulvey. And despite the department’s tight lips about the funds’ balance and all its uses, some of the expenditures known—such as a weekend getaway for the department’s top brass at one of Long Island’s most luxurious East End resorts—only further foments suspicions regarding their utilization among academic and legal experts and those who’ve spent careers within law enforcement overseeing such resources.

“Certainly [they’re] trying to hide something,” says David B. Smith, a former criminal prosecutor in the criminal division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Alexandria, Va. “If they didn’t have something to hide, they would give it to you.” Smith served as the first Deputy Chief of the Asset Forfeiture Office at the Justice Department and was responsible for supervising all forfeiture litigation in the country. “It may not be illegal but it looks dubious.”

“If you did nothing wrong, show it,” charges William J. Kephart, president of the Nassau Criminal Courts Bar Association, representing more than 150 defense attorneys throughout the county. “There’s a reason why you’re not showing it. And you can go with any excuse you want, but the plausible, credible, reliable answer is, that either way, I want to see it.”