Crime Pays

Asset forfeiture money has long been a way for police departments to get extra funding. By confiscating equipment used in a crime, the proceeds of a crime, or items purchased with those proceeds, asset forfeiture is designed to strip criminals of their ability to continue illegal activities. It also has financial benefits for the police, and ultimately, the taxpayer.

Consequently, strict guidelines govern the spending of these funds. The basic premise is that the money is meant to supplement, not supplant, a police department’s budget. For example, recurring ordinary expenses, such as vehicles, uniforms or overtime, among others, for any police department are part of its budgeted fiscal plan. Forfeiture money may only be used to enhance law enforcement as a one-time expense for things not already funded, for example, a helicopter, boat, or even additional bullet-proof vests. Another example of a legitimate expense would be advanced high-tech lab equipment, which could have been used to upgrade the department’s troubled lab, say experts.

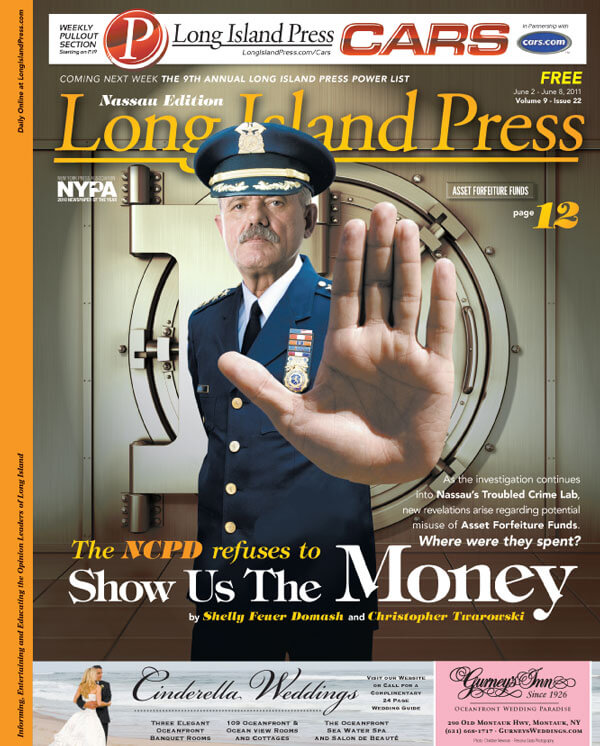

In Nassau, asset forfeiture equals big bucks. And despite NCPD’s recent nondisclosure, past police commissioners—such as Mulvey’s predecessor, Commissioner James Lawrence—readily made available records of purchases and all requests for funding within the department, without FOIL requests and without delays.

From 2002 to 2007, for example, Nassau’s forfeiture unit averaged more than $2 million annually in seizure money, a Press reporter, then writing for The New York Times, learned—without a FOIL. That allowed for major additions to law enforcement capabilities without any cost to taxpayers. Among those purchases: two fast-response boats for the North and South Shores, which cost $500,000; Global Positioning System devices that were installed in 207 patrol cars, to the tune of about $532,000; and hazardous-materials suits and tactical gas masks for every member of the department, which came in at $750,000. The NCPD converted an elementary school into its current police academy in Massapequa using asset forfeiture money and also replaced its photo evidence system with digital-imaging equipment—which cost more than $1 million—with these funds.

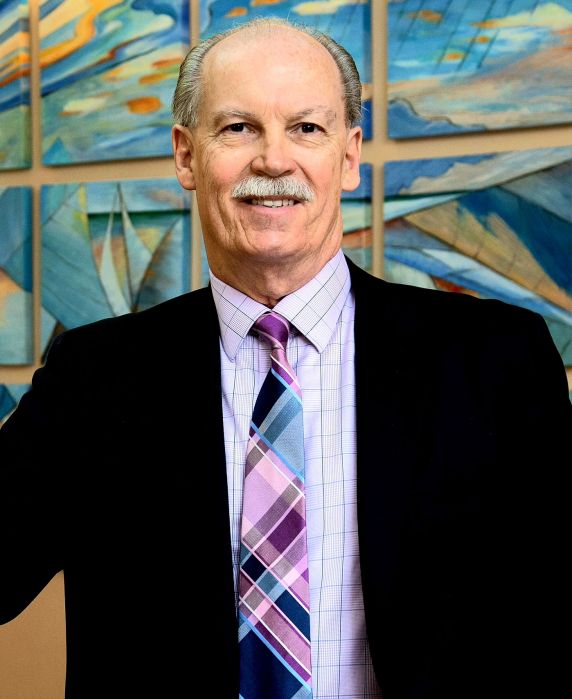

Changes happened quickly within the asset forfeiture bureau following Mulvey’s appointment to the commissioner’s office by then-Nassau County Executive Tom Suozzi in 2007, current and former Nassau police and forfeiture unit members tell the Press.

One of his first decisions was to appoint a new commanding officer to oversee the unit’s operation. For the first time in the unit’s history, a sergeant with no command or legal experience was appointed to head it. That sergeant was William Flanagan. After months of allocating the funds in that capacity, he skyrocketed through the ranks, ultimately becoming appointed to be second deputy commissioner, his current title. Flanagan did not return several requests for comment regarding asset forfeiture funds and the Press’ pending, unfulfilled FOIL request.

For the unit, it was a drastic shift. Since its inception in 1992, it had always had a lieutenant who was also a lawyer in charge. In part, this was to ensure that the maze of legal technicalities and guidelines were adhered to.

Mulvey justified Flanagan’s appointment in an interview with the Press prior to his April retirement. He explained it was not a requirement, adding that other police departments do not necessarily have attorneys as their units’ commander. Along with appointing a new commanding officer, however, Mulvey also inserted himself into the unit’s funds allocation decisions.

It’s a move the former commissioner speaks freely about.

“All requests for purchases come to me and are approved by me, then sent to the committee to approve, table or adjust,” he told the Press several months ago.

Former commanders of the unit, however, interviewed extensively between 1998 and 2007, continuously stressed their dedication to making the process of forfeiture expenditures transparent and free from any political influence.

Beginning with the first commander, Lt. John Kennedy [who declined to comment for this story], every lieutenant since then has warned of the potential of abuse in relation to the distribution of this forfeiture money.

They stress that the procedures were set up to protect the integrity of the unit’s funding. One way they did that was having all requests for forfeiture money come directly to their office, they explain, where the monies were held for a committee to review. That committee was comprised of the four highest ranking chiefs in the department: the Chief of Patrol, Chief of Support, Chief of Detectives and the overall Chief of Department.

These meetings were held four times a year, and the police commissioner did not attend. The procedure was designed so that no one person would have an influence on the decision-making and to ensure that all spending decisions adhered to strict guidelines, they say.

Yet according to former Commissioner Mulvey, in addition to having gotten the requests first, he also attended these quarterly meetings. Consequently, former asset forfeiture bureau officers contend to the Press that since every representative at that meeting worked for the commissioner, their independent decision-making had the potential of being compromised.

Mulvey stressed pride in his participation and his choices of where to allocate funds, stating that “I’ve leveraged it probably more than any other police commissioner to fight crime.”

He touts the implementation of the ShotSpotter Gunshot Detection System in Roosevelt and Uniondale as proof of his wise stewardship of the monies; also, the joint initiative between the NCPD and Nassau District Attorney’s Office of the Gun Buy Back program, in which residents can anonymously drop off firearms for $200 a piece.

Former detectives who worked in the asset forfeiture bureau disagree. They say many of the initiatives that are publicized by the county through periodic press releases are merely window dressing.

“The idea of using seizure funds has always been a good public relations move, but prior to Mulvey’s tenure other commissioners did not spend forfeiture funds to garner good publicity,” one tells the Press. “The fact that the department refuses to release details of their expenditures only creates more suspicion.”

“[Mulvey] has leveraged it more than other police commissioners to promote himself and the county executive,” agrees another former detective.