Two years ago Wednesday, the infamous Superstorm Sandy slammed Long Island, knocking out utilities, leaving thousands homeless and washing out roadways—leaving in its wake a recovery effort that is still continuing.

Stories that emerged in the aftermath ranged from heartbreaking tales of neighborhoods swamped in floodwaters to uplifting anecdotes about communities rallying together to support one another. It brought out the best in many, but some saw it as an opportunity to make fast cash. Despite the widespread devastation, there was a bright side.

“Superstorm Sandy was a tragedy that wreaked havoc on the metropolitan area, but…there is a silver lining,” U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) said, referring to what he called “a historic $17 billion federal investment has been spent to make New York’s infrastructure more resilient, greener and stronger.”

About 150 lives were lost in the storm, including 53 in New York—13 of whom were on LI. Millions were displaced across the East Coast, with about 40,000 in The Empire State. Causing $65 billion in damage in the region, the storm was the second costliest on record—behind only Katrina.

Like any catastrophe, winners and losers emerged from the wreckage. What follows is a ranking of those on LI who came out of Sandy for better, or for worse.

WINNER: BAY PARK SEWAGE TREATMENT PLANT

Bays and residents whose homes were flooded with raw sewage were on the losing end of this one. But, after the storm knocked the East Rockaway plant out of service for 57 days, the long-neglected and mismanaged facility—which had been running on emergency generators even before the storm—that serves about 40 percent of Nassau County, was awarded more than $800 million in federal grants. The recovery ensures repairs, upgrades and an 18-foot-high seawall to protect it from the inevitable next big storm. What’s more, the project revived the yet-to-be-funded effort to build a much-needed ocean outfall pipe that would better dilute effluent that has been pumped for decades into the bays, which have suffered.

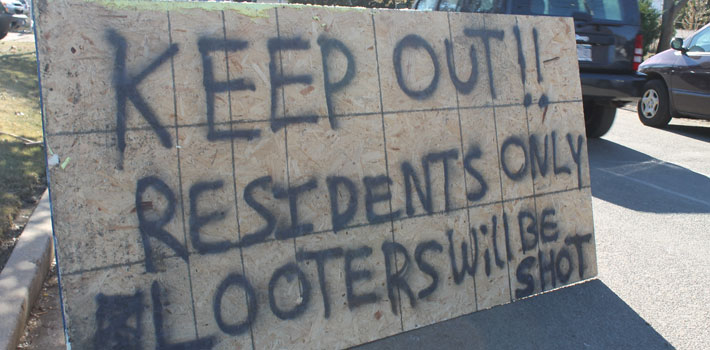

LOSERS: PRICE GOUGERS, STORM CHASERS AND OPPORTUNISTIC THIEVES

When gas station lines ran hours long, contractors had a waiting list and police were in too busy making rescues to fight crime in the days after Sandy, some saw the Island’s weakness as a get-quick-rich scheme. Fifty gas stations on LI and beyond were fined for illegally raising their prices after the storm. Prosecutors charged storm chasers—contractors that come from out of state—with taking hefty down payments from helpless homeowners and then never finishing the repairs. Residents reported people stealing from their damaged, unsecured homes—the worst of which being a Hempstead man who was convicted of raping a woman during an alleged post-Sandy burglary spree. And then there were the assaults on the gas lines, when tempers flared so high that at least two people were arrested for brandishing weapons.

WINNER: BEACHES

New York State wasted no time in rebuilding dunes and pumping sand to rebuild Gilgo through Tobay beaches, thereby buffering Ocean Parkway, which was partly washed out in Sandy. Badly eroded North Shore beaches too, including one in Asharoken village, are getting replacement sand, too. But that’s not all. The Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point Project (FIMP), a storm-mitigation plan for 83 miles of eastern LI coast, had been debated for a half century—often about who was going to pay for it. Then came Sandy. The project was earmarked to get $700 million in the ensuing federal aid package. Interim projects to rebuild the dunes on FI and in Montauk are expected to lead off the massive job. Although a lawsuit by Audubon New York seeking to block the FI plan out of concern for its impact on endangered Piping Plovers was just dismissed, a trickier question looms: Will owners of the oceanfront properties in the way take buyouts or fight condemnation, potentially dooming dune rebuilding?

LOSERS: HOMEOWNERS

Owners of the estimated 100,000 homes that were damaged—and in some cases, totally lost—have had it the worst. Some of the hardest hit are still staying elsewhere, often in trailers in their own yards, while continuing to rebuild. Think those who rebuilt are out of the woods? Not so, since the Federal Emergency Management Agency is reportedly seeking compensation from homeowners it awarded grants to for apparent overpayments. Then there are the 41 oceanfront property owners on FI who face a buyout or possible condemnation if they can’t move their structure out of the way of a planned dune rebuilding project. Not to mention are the countless stories of New York Rising applications left in limbo. And it’s a war on two fronts, with homeowners simultaneously fighting to eradicate hazardous mold spawned in the wake of receding floodwaters.

WINNER: HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS

While the media is often accused of hyping storms to fuel their dark alliance with the milk and bread industries that profit most from pre-hurricane hysteria, studies suggest Sandy’s wrath may change how the public prepares for the next big one. A Stanford University poll last year found that 82 percent of Americans favor hardening structures—such as raising waterfront homes on posts—to mitigate sea-level rise and storms before they happen instead of simply rebuilding along the coast after each hurricane. Fifty-one percent favored retreating from the coast by preventing new shoreline buildings. But the question remains: will the public actually heed the evacuation warnings next time, or will they continue to stay in harm’s way?

LOSERS: WATERFRONT BUSINESSES

Easy access to restaurants overlooking the water is one of the perks of living on LI. But, when a hurricane kicks up a storm surge, that view can prove costly for those restaurateurs. Although many waterside establishments rose to the challenge, others could not. Two in Island Park’s popular bar district, Coyote Mexicano and Paddy McGee’s, which was in business for three decades, closed for good due to the storm damage. Fiore Bros. Fish Market, which opened in 1946 on the Nautical Mile in Freeport, was lost in a fire. Nick’s Tuscan Grill in Long Beach was among an estimated 15 percent of businesses in the City by the Sea that shuttered. And just last month, Molly Malone’s on Maple Avenue in Bay Shore closed after 16 years in business, citing financial trouble partly stemming from the storm.

TIE: LONG BEACH

The seaside city at the center of LI’s westernmost barrier island was home to some of the most dramatic, seemingly post-apocalyptic local images and stories to come out of Sandy. National Guard troops doling out water and emergency food to residents who stayed despite the evacuation order. Narrow streets piled high with debris. A sewage system knocked offline, making it impossible to flush toilets. Cars that floated away, never to be seen again. A nightly curfew that lasted weeks—a distinction shared only with a few hard-hit southwestern Suffolk communities. But, despite all the damage done, the City of Long Beach rolled up its collective sleeves and rebuilt. The boardwalk—the city’s symbol—was torn down and put back together by the next summer. Federal assistance has been pouring in. There’s still a long way to go, however. Its hospital is still years from fully reopening. Vacant properties still dot the landscape, since some owners either chose or were unable to move back. That’s why Long Beach is the only tie on this list.

WINNER: GREAT SOUTH BAY

After Sandy’s powerful storm surge created a breach—one of three—at Otis Pike High Dune Wilderness on Fire Island, Suffolk County officials urged federal officials to fill it in, as had been done with the other two gaps. They warned that it could cause increased flooding of already vulnerable communities closest to the Great South Bay. Two years later, the breach near Old Inlet remains open. Environmentalists, scientists and advocates argue against its closure, saying that the water flowing through the breach between the ocean and bay has improved water quality in the bay, which has been designated an impaired waterway. Once threatened by brown tide, species of fish are returning, scientists have said. Additionally, recent data show that the breach has stabilized. An environmental impact study determining whether the breach should be closed is still in the works. Just in case, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stands at the ready in case a decision is made to close it.

LOSER: LIPA

Long Islanders were mad as hell and they weren’t gonna take it anymore. In 2011, Tropical Storm Irene barreled into LI and knocked out power to a half-million customers, with some outages lasting more than a week. Then Sandy arrived and the damage was more widespread—up to 90 percent of customers were in the dark, some for two weeks—a few even longer. Heads started to roll. Michael Hervey, the chief operating officer for the Long Island Power Authority, and Howard Steinberg, the utility’s chairman, both resigned less than three weeks after the storm hit. Nine months later, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a law that turned LIPA into a holding company and cut its board from 14 members to nine. Essentially LIPA was out and PSEG Long Island was in. “LIPA has offered lackluster service for too long, and after its failure to perform during Superstorm Sandy, it was clear we needed a change,” Cuomo said at the time.

WINNER: BABY BOOM

The idea of procreating amid total destruction seems a bit perplexing, no? Water is everywhere. Power is out. Trees are down. Kids are more agitated than usual. Everyone’s hungry. Gas lines are longer than those at the Apple Store on Christmas Eve. But when the power goes out for a week—or more—and there’s no Internet or TV, the next best thing is passionate, who-the-hell-cares-since-everything-is-falling-apart-around-us sex. Maybe even more than once a week! And then nine months later the fruits of that blacked out (we’re talking about the power) lovemaking emerged in a boom of beautiful and healthy baby boys and girls. Ok, so maybe the media like to push this so-called trend whenever disaster hits, and more than a few outlets claim to have debunked this theory, but the stats don’t lie—at least on the Island. Several hospitals were unable to provide data as of press time, but Newsday reported last year that Nassau University Medical Center saw a 16-percent spike in July 2013 compared to the year prior, North Shore LIJ reported 94 more babies during that same time, and Stony Brook University Hospital counted 13 more newborns, a slimmer baby bump. It’s unclear how many, if any, were named Sandy.

LOSER: WESTERN BAYS

The approximate 64.5 million gallons of effluent discharged daily into the Western Bays from four sewage treatment plants in Nassau was nothing compared to the more than 2 billion gallons of barely treated sewage—much of it raw human waste—that spilled into Reynolds Channel from Bay Park Sewage Treatment Plant after it failed during Sandy. That waterway directly connects to Hempstead Bay, which in 2006 was listed as impaired by the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) due to excessive nitrogen pollution. A DEC study released in May highlighted how nitrogen pollution is threatening marshlands along the South Shore. “The Hempstead Bay/Western Bays area that is being impacted by current discharges from the Bay Park Plant is characterized by extensive marshlands—natural infrastructure, if you will—that is being destroyed by the noxious action of nitrogen pollution,” researchers wrote.

WINNER: CHARITY, COMMUNITY SPIRIT

Amid the life-altering chaos in the most Sandy-ravaged communities on LI, there was always someone or some group out on the streets, either giving out blankets or food, or helpful phone numbers for government assistance. The Red Cross and other nonprofit relief groups deployed their resources. Religious groups from across the nation descended on LI to help people of all faiths. There were also regular Long Islanders, like those who set up Camp Bulldog in Lindenhurst, a community group that came together to provide basic necessities to their hurricane-stricken neighbors. One couple went to McDonald’s, bought nearly 100 burgers and walked around Babylon, handing them out to homeowners rebuilding their lives. And 24 months later, dozens of relief groups still working remain like the one at the Disaster Recovery Center in Central Islip, trying to help survivors put the pieces back together. Maybe it’s true that communities only come together during tragedies. That’s OK, because when it happens, it’s a beautiful thing to see.

LOSER: HALLOWEEN

The superstorm knocked out our power, felled trees, destroyed homes and cars—and if that wasn’t bad enough: It shut down Halloween of 2012. Instead of seeing mom and dads walking hand-in-hand with their creepy, crawly infants or kids donning the outfit of their favorite superhero or princess as they went door-to-door shouting “Trick or Treat” in pursuit of a month’s-worth of candy, neighborhoods involuntarily plunged into complete darkness were eerily quiet. Some had some choice words for the hurricane-that-shall-not-be-named. Police and local officials sent out alerts asking residents to celebrate the spooky holiday indoors—(!!!)—to avoid downed wires and other debris. In Nassau, Halloween was postponed until Nov. 2 for families who wanted to enjoy the festivities at the Theodore Roosevelt Executive and Legislative Building. Thanks, but no thanks. From now on we’ll celebrate every Halloween to its fullest, never forgetting the lost Halloween of 2012.