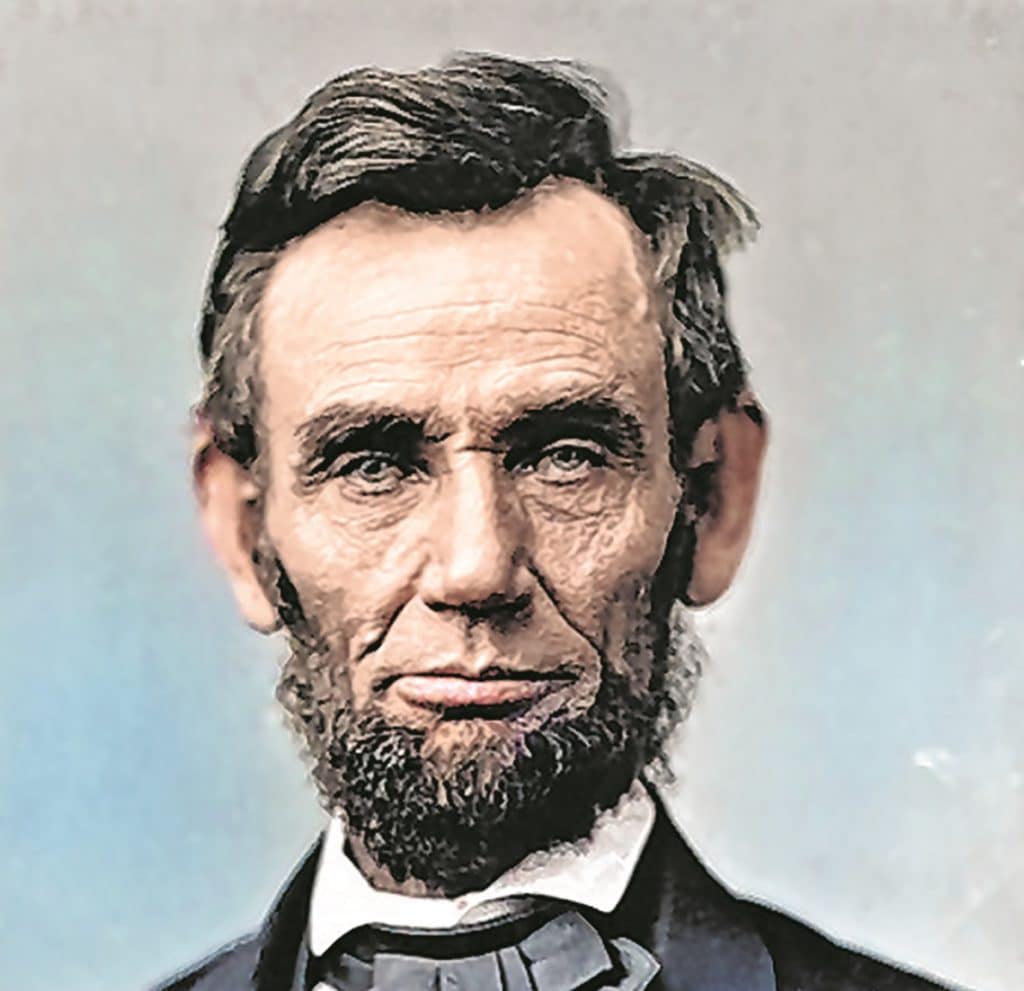

If George Washington took advantage of his time on the New York stage, the same is true of Abraham Lincoln. It’s hard to imagine, but Lincoln going into the cataclysmic 1860 election was not a household word. Lincoln had already lost his most recent race, the legendary 1858 Illinois senate campaign between Stephen A. Douglas and himself. Along the way, however, he earned devoted followers among the GOP faithful.

Lincoln came out of nowhere to receive the Republican Party’s 1860 nomination. “I have a taste for it,” he said, when asked if he was interested in being the fledging party’s standard bearer. Few people gave him a chance.

The GOP’s field for the 1860 campaign was in turmoil. Party leaders and the Republican newspapers were unhappy with the candidates, especially New York’s William Henry Seward, who was considered too extreme and too confrontational to win the White House. Seward needed to be defeated in his home state.

On Feb. 2, 1860, Lincoln was invited to give an address before the Young Men’s Central Republican Union of New York. The speech was originally scheduled to take place at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. It was soon rescheduled for Cooper Union in Manhattan. This was a most fortuitous development. A speech in Brooklyn would have garnered press attention. In Manhattan, however, Lincoln was able to reach a cultural, political and financial elite, exactly the forces that can propel an unknown into national politics.

Among the speakers preceding Lincoln were Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Tribune and he of “go west, young man” fame and Roslyn’s own William Cullen Bryant, famed poet, noted abolitionist and editor of The New York Evening Post. The presence of these two gave instant credibility to Lincoln’s political ambitions.

Lincoln was a born politician—and a born rhetor. He wrote his own speeches, memorable for their brevity and pointed statements. The Cooper Union address was different in that its length—7,000 words—was significantly greater than the average Lincoln speech.

To understand Abraham Lincoln, one must know Henry Clay. Without Clay, there probably never would have been the Lincoln that history knows. What Lincoln shared with his fellow Kentuckian was a belief in Union, a yearning for compromise, the protective tariff, a modern banking system and the desire to repatriate the freedman to another country once slavery was abolished, a view he later dropped in favor of granting the franchise to former slaves who owned private property.

In the speech, Lincoln claimed that there was a legal case for prohibiting slavery in the western territories.

“The sum of the whole is, that of our 39 fathers who framed the original Constitution, 21—a clear majority of the whole—certainly understood that no proper division of local from federal authority, nor any part of the Constitution, forbade the federal government to control slavery in the federal territories,” the candidate maintained.

Prohibiting slavery in those territories—and not necessarily the abolition of slavery where it existed—was the centerpiece of his policy on that issue. Lincoln also made the case that the Republican Party, far from being fire-eaters themselves, would pursue a conservative course for the nation on all constitutional matters. “What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried?” he asked, distancing himself from extremists in both parties.

Compromise aside, Lincoln called for firmness in the face of America’s greatest crisis.

“Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves,” he concluded. “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

The speech was a resounding success. David Herbert Donald, one of Lincoln’s more accomplished biographers, claimed the man’s entire political career was on the line. A failure and Lincoln returns to oblivion. The speech worked because it gave the Republicans a middle ground candidate, one who was anti-slavery, but willing to compromise and dialogue with southern slave owners. Lincoln’s protectionism decisively put the GOP on the popular side of an issue that was even more divisive than slavery.

The speech was greeted with a rousing ovation, with attendees waving handkerchiefs and hats. The text was reprinted in newspapers across the country. Greeley hailed Lincoln as “one of Nature’s great orators, using his rare powers solely and efficiency to elucidate and to convince, through their inevitable effects is to delight and electrify as well.”

The GOP had found their man. With the Democratic Party in turmoil, Lincoln was elected president with 40 percent of the vote. The Republican Party was now established as a governing party. The speech was the easy part. Ahead would lie the secession of the lower South, the firing on Fort Sumter, the secession of the Mid-South states, the greatest war in the history of the Western hemisphere, the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s re-election, the magnanimous surrender at Appomattox, followed by Lincoln’s own assassination. His presidency, especially with the protective tariff, laid the groundwork for the GOP’s domination of the White House from 1865 to 1932, when the Great Depression ushered in the Democrats’ own reign.