Amelia Earhart and Her Courageous Flights Had Long Island Ties

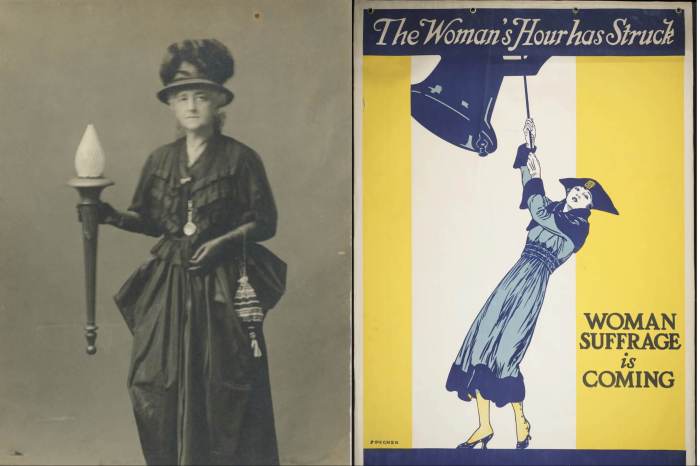

She was an iconic aircraft pilot in an age when a woman at the controls in the cockpit was a rarity. But many other women were also flying all across Long Island, and they came together in 1929 as The Ninety-Nines to promote the advancement of aviation.

The group was based at Curtiss Field in Valley Stream, where Green Acres Mall now stands. Along with Curtiss Field, later named Columbia Field, Long Island’s Roosevelt Field and Mitchel Field were favored by many aviators. One of them was Amelia Earhart: She helped to found The Ninety-Nines, was its first president, and set aviation records.

And then she and her plane disappeared somewhere over the Pacific Ocean.

During her time on Earth, she captured the public’s admiration, as illustrated by singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell’s lyrics of the song “Amelia:”

A ghost of aviation

She was swallowed by the sky

Or by the sea like me she had a dream to fly.

And fly she did. She explained why, writing, “Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others.”

FROM COLLEGE DROPOUT TO TRAILBLAZER

Born in Atchison, Kansas in 1897, Amelia Mary Earhart was described as a daring tree-climbing tomboy with an independent spirit. The tall, slender blonde who kept a scrapbook on women succeeding in prominently male-dominated fields attended her first stunt-flying exhibition in her early 20s in 1918. But it was her first plane ride two years later that got her hooked, she said: “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I myself had to fly.”

To save up the $1,000 cost of pilot lessons, she worked as a seamstress, a stenographer, a telephone company clerk, and a truck driver, dropping out of college to pursue her love affair with the sky. In 1921, she took her first solo flight and began to build a name for herself.

“Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others.” –Amelia Earhart

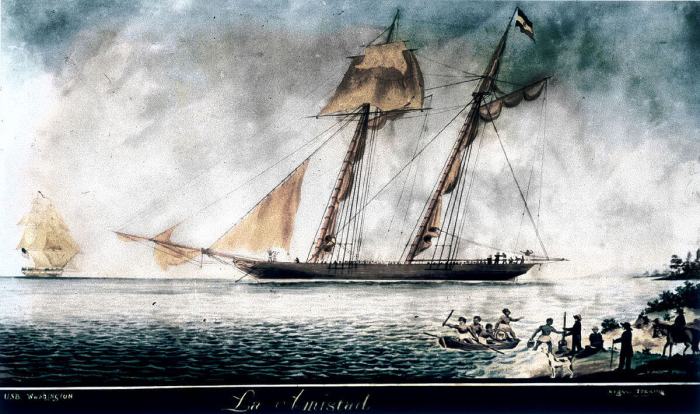

Another woman, the owner of Old Westbury House (now Old Westbury Gardens) supported Earhart’s efforts. Long Island Gold Coast socialite and steel heiress Amy Phipps Guest, who owned at least a half-dozen grand North Shore estates built from the 1890s to the 1930s during the Gilded Age, was deeply interested in aviation and bought a monoplane, the Friendship. Guest wanted to sponsor the flight and be the first female passenger to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

But her family urged against her going on the dangerous 21-hour flight, so Richard Byrd and publisher/publicist George Palmer Putnam selected Earhart, who at the time was a Boston social worker working with immigrant families. But even though Earhart had about 500 hours of flying experience, she didn’t pilot the plane: She was, instead, the aircraft commander with pilot Wilmer L. Stultz and co-pilot/flight mechanic Louis E. Gordon. Several years after the 1928 fight, she and Putnam were married. Earhart referred to their marriage as a “partnership” with “dual control,” according to her official website.

The Ninety-Nines was established shortly after the 1929 Women’s National Air Derby, dubbed “The Powder Puff Derby” by humorist Will Rogers. The 99 charter members, many from Long Island, formed the women’s organization for social, recruitment, and business purposes. In 1931, the group elected Earhart as its first president. Drawing on her seamstress and design skills, she designed a two-piece flying suit for the group; the group never formally adopted the outfit but did keep its interlocking “9s” as their logo.

Racking up more aviation achievements, in 1932 Earhart became the first woman to fly nonstop and solo — and the only person after Charles Lindbergh — across the Atlantic Ocean. Her drive propelled her through the hazards of the 2,000-mile, 15-hour trip: she “fought fatigue, a leaky fuel tank, and a cracked manifold that spewed flames out the side of the engine cowling. Ice formed on the plane’s wings and caused an unstoppable 3,000-foot descent to just above the waves,” as described by the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

Her next journey was “harder than flying the Atlantic,” she said: She soloed from Hawaii to California, a 2,500-mile, 18-hour flight, in 1935, a feat that further cemented her international popularity. The strong-willed aviatrix became a celebrity, promoting careers for women, visiting the White House, and lecturing at colleges. The New Yorker magazine wrote that Earhart “urged the coeds to focus on majors dominated by men, like engineering, and to postpone marriage until they had got a degree,” despite the fact that she never earned a degree. As the publication compared her with distinguished pilot Lindbergh — both were “lean, fair Midwesterners with winning smiles” — she set her sights on her next challenge.

UNSOLVED AERIAL MYSTERY

Approaching 40, she planned to circumnavigate the globe. Piloting her twin-engine Lockheed Electra, Earhart took off from California on June 1, 1937 with navigator Fred Noonan. A month later, on July 2, they departed from Lae, New Guinea, headed for tiny Howland Island in the middle of the Pacific, the longest, most dangerous lap of the 29,000-mile trip. But catastrophic failures beset them: Radio transmissions kept cutting out; they were unable to use Morse code; their maps showed incorrect coordinates for their destination; their fuel supply was low.

On July 2, at 8:43 a.m., Earhart broadcast her final message. After an extensive search, on July 19 the U.S. government discontinued rescue attempts. Numerous theories still swirl around her disappearance, and prestigious companies have conducted searches. However, says Robin Hadfield, president of The Ninety-Nines, “No definitive evidence has been found to date, and the mystery of Amelia Earhart’s disappearance remains unsolved.”

In a letter written to her husband before the flight, Earhart said, “Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it.”