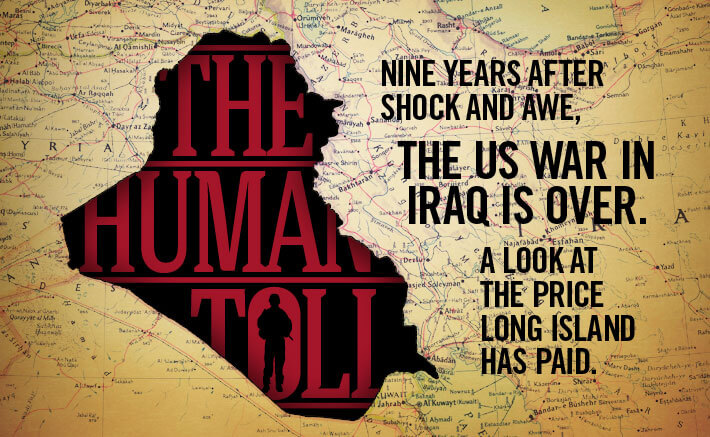

LAST CALL FROM IRAQ

One Saturday morning in July 2007, Tim Scherer and his wife Janet were sitting in their den at their home in East Northport when the news came.

“I was looking out the window and my wife was talking to me,” recalls Scherer, a former stock broker who runs the Vetsbuild “green construction” training program at United Veterans Beacon House in Bay Shore. “The next thing I knew I saw a woman in her greens come up onto the deck… I just froze… I was confused for a minute, but then I saw the second Marine come up. My wife saw my mouth fall; it must have hit the ground, and she turned around and started screaming, ‘Don’t open the door!’”

Their 21-year-old son had been killed by a sniper while stacking sand bags in Iraq. He’d been shot through the armpit, where his body armor could not protect him. Corporal Christopher G. Scherer had wanted to enlist right after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, but his father persuaded him to wait. He became an Eagle Scout and played varsity lacrosse at Northport High School. A month after he graduated in 2004, he was in boot camp on Parris Island, S.C. In the spring of 2007, he and his fellow Marines of the 1st Combat Engineer Battalion, 1st Marine Division, left Camp Pendleton, Calif., for Kuwait, where he earned the rank of corporal on his mother’s birthday, June 1.

“He was ecstatic when he got the rank of corporal,” Scherer recalls. “He was fulfilling one of his dreams. You can go through your whole life without finding that job that you love, and he enjoyed what he was doing… We have no regrets. We wish it would’ve ended differently—certainly for our son—but our son volunteered to be a Marine… You raise your children and you have to let them fly.”

They had just spoken to their son a few days before his death and he’d asked for pairs of lighter boot socks. “And when we were ready to hang up, he says, ‘Wait! Can you do me a favor? Can you send some extras because some of the other guys don’t have families. They don’t get care packages.’ You don’t know that this is your last phone call with your son,” Scherer says.

He e-mailed his son’s request to his friends for help and soon he’d received $2,500 to buy supplies for his son’s platoon. He shipped the packages to Iraq but Chris had died days before they arrived and every package was returned unopened. Then Scherer sent the supplies to his son’s friend who was also serving in Iraq and “that’s how we got started.”

Before this Gold Star dad became a case worker for Beacon House’s Vetsbuild program, Scherer, his wife, and his older son and two twin daughters decided to honor Chris by setting up a college scholarship that has since blossomed into the “Semper Fi Fund,” the “Leave No Marine Behind Project” and “Team Chris.” With the help of other volunteers they’ve sent monthly care packages to men and women serving in harm’s way.

For four years now on Memorial Day weekend, they’ve also sponsored a “I Did the Grid” fund-raiser in East Northport, which Scherer describes as “the Fenway Park of road racing…it’s 31 turns. You actually run up and down every block Chris grew up on…” Neighbors line the streets for the race, which starts and ends at Pulaski Road School, and there’s something for runners (and walkers) of every caliber, from a four-mile competitive run to a one-mile run for fun. The next one is Saturday, May 26.

“Doing what I do here keeps Chris on my mind but not in a negative way,” says Scherer. “If he’d come home, I’d be fighting for him to get a job.”

Like Scherer and many others who volunteered to join the fight, Sgt. James Regan saw 9/11 as a call to arms. Unlike many others, he passed up a law school scholarship to enlist, serving two tours in Afghanistan before his second tour in Iraq ended in an IED blast that killed the 26-year-old Manhasset man.

His family keeps his name alive with the Lead the Way Fund, a nonprofit dedicated to filling the gap in government assistance to the families of fellow Army Rangers who’ve died, been wounded or are still serving. Assisting a segment of the service that falls under the Special Operations Command, which is heavily used in the broader War on Terror, has become the fallen soldier’s last—and lasting—mission, filling a void among nonprofits dedicated to special ops units.

“It needed to be done,” says Regan’s father, James, chairman and CEO of the fund. “You can only imagine being the spouse of a Ranger who’s been deployed 10 times.”