Joe Namath is back with a short autobiography. All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters is co-written with Sean Mortimer and Don Yaeger. Every chapter recalls the 1969 Super Bowl III win over the Baltimore Colts. “I was just responding to a question!” Namath protests over his famous “I guarantee it” victory promise. Namath takes the reader through his childhood and adolescence in Beaver Falls, PA, where he starred in both baseball and football at Beaver Falls High School. Western Pennsylvania is the mother lode of quarterbacks: Namath, George Blanda, Johnny Unitas, Dan Marino, Joe Montana, Joe Theismann and Jim Kelly. The game has never seen anything like it. Next up was the University of Alabama and his equally legendary career as the Crimson Tide’s starting quarterback in the early 1960s, when that team dominated college football. Paul “Bear” Bryant, Alabama’s storied head coach remains the adult figure that Namath admires above all men. Namath will always love New York and vice versa, but the man’s heart is at game day on a fall afternoon in Tuscaloosa.

Joe Namath is back with a short autobiography. All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters is co-written with Sean Mortimer and Don Yaeger. Every chapter recalls the 1969 Super Bowl III win over the Baltimore Colts. “I was just responding to a question!” Namath protests over his famous “I guarantee it” victory promise. Namath takes the reader through his childhood and adolescence in Beaver Falls, PA, where he starred in both baseball and football at Beaver Falls High School. Western Pennsylvania is the mother lode of quarterbacks: Namath, George Blanda, Johnny Unitas, Dan Marino, Joe Montana, Joe Theismann and Jim Kelly. The game has never seen anything like it. Next up was the University of Alabama and his equally legendary career as the Crimson Tide’s starting quarterback in the early 1960s, when that team dominated college football. Paul “Bear” Bryant, Alabama’s storied head coach remains the adult figure that Namath admires above all men. Namath will always love New York and vice versa, but the man’s heart is at game day on a fall afternoon in Tuscaloosa.

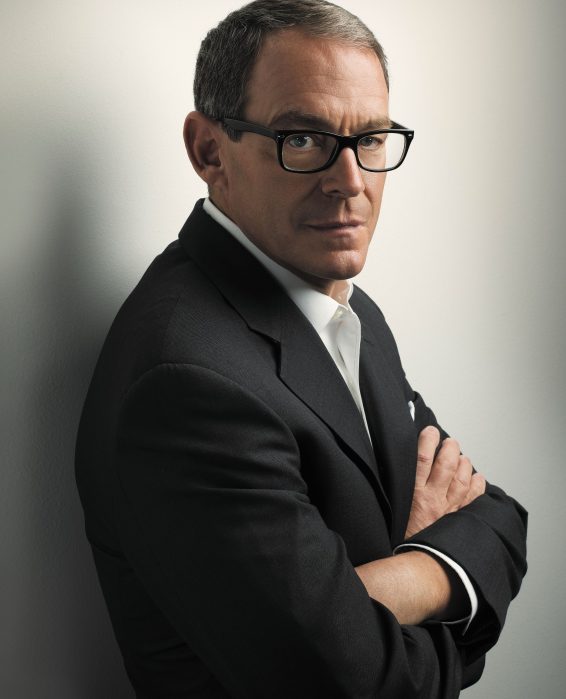

Fresh off biographies on Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor and Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Biskupic takes on John Roberts, current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts). Biskupic tells the story of an ambitious young man who penned a heartfelt admission letter to an elite boarding school in his native Indiana, as a way to achieve a step-up in the world. Roberts was inspired by President Ronald Reagan’s 1981 inaugural address and was determined to be an effective foot soldier in the Reagan Revolution. He spent the 1980s at the Justice Department and later was appointed to the Washington, DC circuit court before becoming George W. Bush’s choice to succeed William Rehnquist as chief justice. Biskupic examines his record as chief justice. She is critical of his decisions on voting rights, school busing and corporate money in politics and union issues. Roberts, too, cast the deciding vote affirming the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). With Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch now on the court, which John Roberts will stand up: The justice who promised to be a fair and impartial referee or the fifth vote of a conservative majority?

Fresh off biographies on Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor and Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Biskupic takes on John Roberts, current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts). Biskupic tells the story of an ambitious young man who penned a heartfelt admission letter to an elite boarding school in his native Indiana, as a way to achieve a step-up in the world. Roberts was inspired by President Ronald Reagan’s 1981 inaugural address and was determined to be an effective foot soldier in the Reagan Revolution. He spent the 1980s at the Justice Department and later was appointed to the Washington, DC circuit court before becoming George W. Bush’s choice to succeed William Rehnquist as chief justice. Biskupic examines his record as chief justice. She is critical of his decisions on voting rights, school busing and corporate money in politics and union issues. Roberts, too, cast the deciding vote affirming the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). With Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch now on the court, which John Roberts will stand up: The justice who promised to be a fair and impartial referee or the fifth vote of a conservative majority?

Dave Eggers’ eighth novel, The Parade, is a short, tense tale about an unnamed nation in the throes of surviving a civil war that has left death and destruction on both sides. Two men, “Four” and “Nine” are hired to paint a yellow line from the new nation’s two-lane road from the countryside to its largest city. Four is all business. With a wife and daughter back home, he just wants to get the job done. Nine, on the other hand, is out for a good time. He happily mingles with the locals, in ways both innocent and not-so-innocent. It gets them both into big trouble. The terse novel will remind readers of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, about a father and son who are survivors of a nuclear war, plus the equally-bleak fiction of Don DeLillo.

Dave Eggers’ eighth novel, The Parade, is a short, tense tale about an unnamed nation in the throes of surviving a civil war that has left death and destruction on both sides. Two men, “Four” and “Nine” are hired to paint a yellow line from the new nation’s two-lane road from the countryside to its largest city. Four is all business. With a wife and daughter back home, he just wants to get the job done. Nine, on the other hand, is out for a good time. He happily mingles with the locals, in ways both innocent and not-so-innocent. It gets them both into big trouble. The terse novel will remind readers of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, about a father and son who are survivors of a nuclear war, plus the equally-bleak fiction of Don DeLillo.

John Lukacs: In Memoriam

This past May, America lost one of its greatest historian with the passing of John Lukacs at age 95. A native of Hungary who fled to the United States in the later 1940s, Lukacs was the author of more than 30 books, including such provocative classics as Four Days In May, Outgrowing Democracy, Historical Consciousness, A Thread Of Years and A Short History Of The Twentieth Century.

To Lukacs, history was a wild ride, full of those cunning passages and contrived corridors fate is heir to. The study of history is infinitely rewarding: Unpredictable, surprising, sobering and hopeful. Lukacs never ran out of books to write, he simply ran out of time. An accessible prose stylist, Lukacs’s great subject was the twentieth century. Its defining moment came in May 1940, when Winston Churchill was determined to confront Adolf Hitler. It was a closer call than people imagine. Members of the ruling cabinet counseled in favor of an agreement with Berlin. Churchill said no. For Lukacs, this was correct on two counts. First, there was the obvious geo-strategic reasons: Hitler had conquered the continent. He had to be stopped somewhere. There was also an ideological reason. The century was defined by various “isms”: communism, fascism, socialism, capitalism. Of this quartet, fascism, with its emphasis on blood and land, plus scapegoating of “the other,” had the potential to be the most powerful of all. Stop it in its tracks.

To Lukacs, history was a wild ride, full of those cunning passages and contrived corridors fate is heir to. The study of history is infinitely rewarding: Unpredictable, surprising, sobering and hopeful. Lukacs never ran out of books to write, he simply ran out of time. An accessible prose stylist, Lukacs’s great subject was the twentieth century. Its defining moment came in May 1940, when Winston Churchill was determined to confront Adolf Hitler. It was a closer call than people imagine. Members of the ruling cabinet counseled in favor of an agreement with Berlin. Churchill said no. For Lukacs, this was correct on two counts. First, there was the obvious geo-strategic reasons: Hitler had conquered the continent. He had to be stopped somewhere. There was also an ideological reason. The century was defined by various “isms”: communism, fascism, socialism, capitalism. Of this quartet, fascism, with its emphasis on blood and land, plus scapegoating of “the other,” had the potential to be the most powerful of all. Stop it in its tracks.

Lukacs’s view of his adopted homeland was no less sanguine. In Outgrowing Democracy, Lukacs seemed both bemused—and critical—of American materialism, dramatized by its obsessive car culture. In an expanded edition, A New Republic, he mocked the idea of America as the “supreme rulers” of the planet. With its “last, best hope on earth” credo, America, to Lukacs, was in fact a deeply pessimistic nation. He worried that mighty America might yet become a burnt-out case.

For Lukacs, all roads led to 1940. He praised Churchill for giving the West “50 more years.” What happens after 1990? Lukacs saw the rising populism in today’s Europe as revealing echoes of the 1930s, an observation I find dubious. In A Short History Of The Twentieth Century, Lukacs was strong on World War II, the Cold War and the postwar era. The historian also admitted weaknesses when confronting World War I. Did not the time of troubles actually begin in August 1914? Or had the two world wars simply sucked the life’s blood out of the West? The man, if still with us, would have enjoyed rebutting your servant. Get out your library card, rush to the bookstore or log onto to Amazon to discover the ever-expanding universe of John Lukacs.