Back in November 2017, almost 50 protestors gathered outside the East Setauket offices of Renaissance Technologies. It was a small protest for a low-profile hedge fund whose leaders had become involved in high-profile politics. Renaissance Technologies’ website is by invitation only: It eschewed publicity and does not let the public invest in its most well-known fund. But its executives had become lightning rods among some concerned that wealthy donors were tipping the political scales in their favor and, in this case, possibly seeking to stave off a $7 billion tax bill.

The protestors that day opposed a tax plan that, they said, would primarily benefit the wealthy, but they also were motivated by other issues, including a massive tax bill that, at least so far, was being challenged and not paid. And then there was the fund’s executives involvement as among the nation’s biggest political donors.

The protestors initially sought to gather outside the home of Robert Mercer, then co-CEO of Renaissance Technologies, who had helped fund Donald Trump’s campaign. Some credited him with helping get Trump, who had recently attended a Halloween party at Mercer’s house, elected.

After Suffolk police prevented the protestors from parking near the property, they reassembled outside Renaissance Technologies’ headquarters.

The nearly 50 people belonged to groups such as New York Communities for Change, New York State United Teachers, the Communication Workers of America locals 1108 and 1104 and North Country Peace Group.

They carried signs such as “Educators Know Arithmetic” and “Students over billionaires” and a mock $7 billion check, based on a tax case Renaissance faced.

The Internal Revenue Service and a Senate committee had determined that Renaissance owed $6.8 billion, but Renaissance was fighting the IRS decision. Renaissance had been founded by Jim Simons, a world-famous mathematician. But according to the IRS, it got its tax numbers woefully wrong, classifying trades as long-term rather than short-term gains with higher rates.

To protestors, that tax case was emblematic of the way Washington worked. The IRS determined the bill, and yet nothing had been paid for years. At least at the time, it looked like that mock check would never give way to a real one. The tax bill passed soon after the protestors went home, but that nearly $7 billion tax bill, although it might surprise those protestors, stayed due for years. It’s now being paid.

Renaissance Technologies has agreed to settle the IRS case, reportedly for about $6.8 billion, in what’s being touted as the biggest tax settlement in history. It’s double GlaxoSmithKline’s $3.4 billion, to settle tax issues pertaining to the British company and its American subsidiary. That $7 billion mock check will now be real and there is widespread reporting of the settlement. Seven current and former executives will foot the bulk of the bill with Medallion fund investors picking up a portion.

While the settlement is making news, the story of the case, the company and hundreds of millions of contributions, which may have delayed but did not derail the tax bill, is largely being ignored. Tucked away in East Setauket, Renaissance went from a famously secretive and successful fund to one that attracted attention. How did a low-profile hedge fund become embroiled in this high-profile tax case? How and why did its executives become among the nation’s biggest political donors? And did this tax case motivate or ramp up that involvement, helping elect a president and modifying tax codes, even if Renaissance would settle the tax case in the end?

Math to money

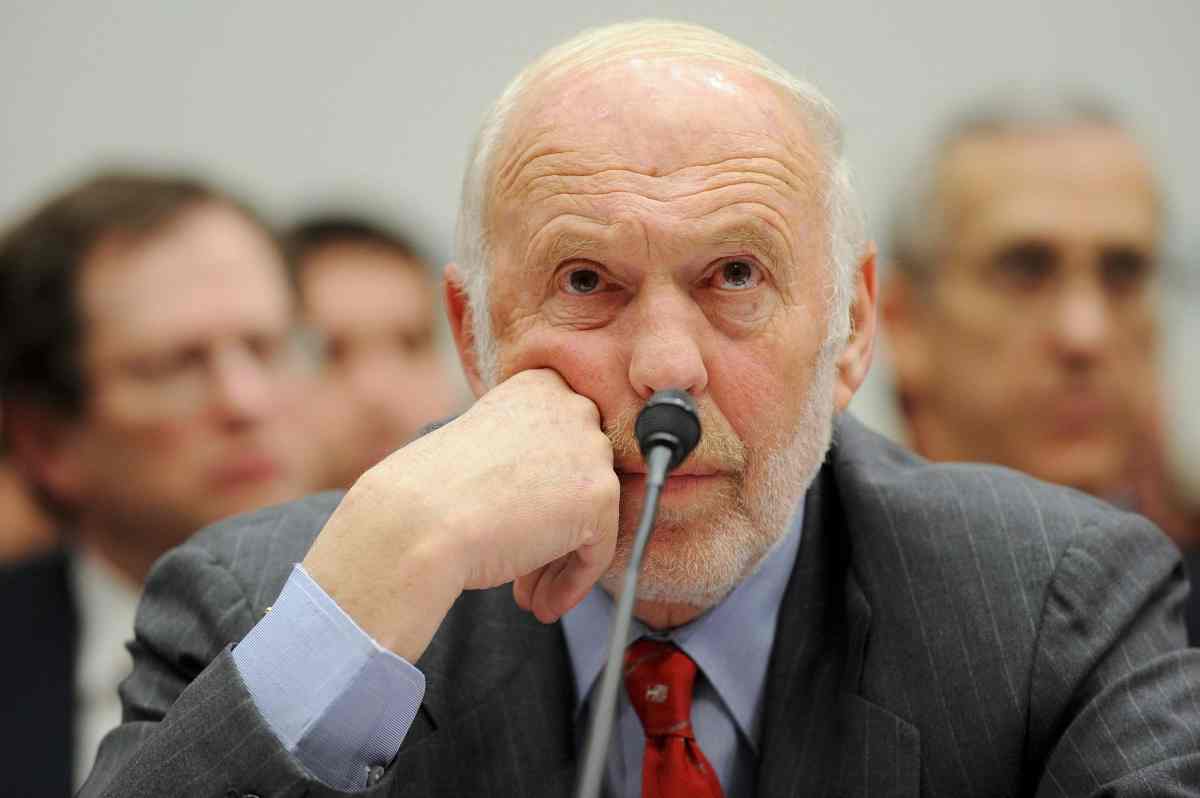

James Simons is the kind of success story many Americans dream of, even if he won’t show up on Shark Tank. He worked as a code breaker during the Cold War and then served as Chair of the Department of Mathematics at Stony Brook University for a decade. Simons in 1976 won the Oswald Veblen Prize of the American Mathematical Society. If he won awards, Simons didn’t make that much money at Stony Brook. Professors don’t get paid as well as hedge fund profits can.

And so in 1978, Simons left the nest of academia (although he would late donate hundreds of millions of dollars to Stony Brook) and started Monemetrics, a hedge fund management firm initially trading currencies. He hired more academics and grew the fund, while going far beyond currency trading. And soon Simons had created a company legendary both for secrecy and success.

The company, located in the shadows or nearly a stone’s throw from Stony Brook, was renamed Renaissance Technologies in 1982. The firm in 1988 created the Medallion Fund, legendary for profits. The fund virtually minted money. Medallion, available to Renaissance current and former employees and family, reportedly averaged a 71.8% annual return before fees from 1994 through mid-2014. Since 1988, Medallion reportedly generated average annual returns of 66% before “charging hefty investor fees,” equaling 39% after fees, Gregory Zuckerman wrote in 2019 in ‘The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution.’ The fund racked up trading gains of more than $100 billion, he wrote.

“No one in the investment world comes close, “ Zuckerman wrote. “Warren Buffett, George Soros, Peter Lynch, Steve Cohen and Ray Dalio all fall short.”

Simons wasn’t doing it alone: He brought in mathematicians, academics and a small army of PhDs. As part of that, he in 1993 brought in Robert Mercer and Peter Brown, computer scientists specializing in computational linguistics at IBM. Simons led Renaissance until he retired in late 2009 and stepped down as Chairman in 2021.

The company after Simons stepped down in 2009 was run by Peter Brown and Robert Mercer until Mercer stepped down. If it made money, Renaissance was going to get involved in remaking America as well, first in a one-sided way, but soon in a way that involved major donations to both political parties. Renaissance’s executives were about to play billionaire ball, but not baseball. One of them would swing for the fences, seeking to and succeeding in making a president.

Democratic donations

While Renaissance is legendary for gains, its executives would soon become legendary for political donations – on both sides of the aisle. Simons supported Democrats first, while Mercer became went on to become an early and big Trump donor.

Simons by 2009 had become a big Democratic donor. That year, Margaret Hamburg, wife of Renaissance executive Peter Brown, would be named FDA Commissioner. She had a long resume, yet only emerged as Commissioner after speculation that she would have a different job at the agency. Little attention was paid to the fact that Hamburg was married to Peter Brown, an executive and soon co-CEO of Renaissance. And Hamburg had served in high-profile jobs before, making her role as FDA commissioner arguably a natural next step.

Simons, out of belief, personal benefit or both, was becoming a major Democratic donor and philanthropist. When you’re among the richest people in the nation, donation can go with that territory. In the 2012 elections, Simons contributed more than $9 million to Democrats and/or Democrat supporting PACs. In 2014, Simons donated $340,000 to the Obama Foundation and another $330,000 in 2015. Simons has now donated more than a million dollars to the Obama Foundation/Obama Library, according to Linda Martin, who views herself as a whistleblower regarding Renaissance and political influence.

Simons and Renaissance didn’t just make money; they made massive contributions. Other billionaires would try to go into space; Simons and Renaissance were focused on earth. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Renaissance was the top financial firm contributing to federal campaigns in the 2016 election, donating more than $33 million. Renaissance’s managers reportedly contributed nearly $30 million.

Mercer ranked as the #1 individual federal donor that year, focusing on Republicans. Simons ranked #5, supporting Democrats. During the 2016 campaign, Simons reportedly contributed more than $26 million, while Mercer reportedly contributed about $25 million.

It might seem as if the two cancelled each other out, but another way of looking at it was, deliberate or simply as an outcome of individual actions, Renaissance executives covered both sides of the aisle. They “hedged” their bets or their actions had that effect. Whether a Democrat or Republican won, Renaissance would win. In any case, Renaissance would soon become associated not with the Democrats, but with the discovery and election of Donald Trump.

The dollars behind Donald Trump

While Simons had long supported Hillary Clinton, Mercer would pick the winner – and help him win. And Mercer would soon become among the best known and most successful donors. Nicholas Confessore in The New York Times described Robert Mercer as “a mathematician and competitive poker player who spent his early career at I.B.M., joined Renaissance in the 1990s and rose to become the co-chief executive, earning hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Mercer worked with Peter Brown at IBM, coming over to the firm together and becoming co-CEO. Mercer was listed as #18 on Forbes list of hedge fund managers based on earnings in 2016 at $150 million. He would use his money to influence politics and elect a president. Just as hedge funds pick stocks, he would pick a president.

Mercer began supporting Tea Party candidates and then a political action committee on behalf of Donald Trump and Breitbart News. He became the dollars and the real money behind Donald Trump, who spent little on his own campaign.

“His fortune has financed think tanks and insurgent candidates, super PACs and media watchdogs, lobbying groups and grass-roots organizations,” Confessore wrote in The New York Times while Donald Trump was running for president. “Many of them are now connected, one way or another, to Mr. Trump’s presidential bid.”

Mercer started out funding conventional Republican candidates, supporting Mitt Romney’s presidential run in 2012. Romney, after all, came from the finance world, co-founding Bain Capital in 1984 with Bain & Company partners T. Coleman Andrews III, and Eric Kriss.

Mercer, however, soon moved on to other candidates, supplying $13.5 million for Ted Cruz’s primary run. After Cruz left the field of presidential hopefuls, Mercer discovered, or at least began funding, Donald Trump, including pro-Trump political action committee “Make America No. 1” led by Kellyanne Conway before she became Trump’s campaign manager.

Mercer and his daughter Rebekah Mercer became staunch Trump supporters. They seemed to see something in Trump that others didn’t: He could win.

“America is finally fed up and disgusted with its political elite,” the Mercers said in a rare statement that did not seem to come from a hedge fund magnate. “Trump is channeling this disgust and those among the political elite to quake before the boom-box of media blather.”

The family business

Robert Mercer is a combination of contradictions, at once a member of the “economic” elite and someone who, at least on the surface, opposes the “elite. Or at least, he opposed the Clintons. Mercer funded the book “Clinton Cash” that looked into supposed Clinton conflicts of interest. His daughter Rebekah would become co-executive producer of the hour-long documentary “Clinton Cash.”

Mercer was using money not just to make money, but to remake the nation through media. He reportedly invested $10 million in Breitbart News.

The Mercers invested heavily in Cambridge Analytica, a data analytics company based in England that targeted voters based on personality profiles. The Trump campaign hired Cambridge Analytica after the Mercers began supporting the campaign, tapping social media to move voters.

Bloomberg News reported that Rebekah Mercer, Mercer’s daughter, was appointed to a position on President-Elect Donald Trump’s transition team. Mercer didn’t just help fund Donald Trump; he helped define him. Rebekah Mercer advocated for Jeff Sessions to be U.S. Attorney General.

Robert Mercer also has contributed millions to unseat Sen. John McCain, who had been a vocal voice in concluding Renaissance owed amore than $6 billion in taxes. Whether it was a personal vendetta, financially motivated or simply politics, Mercer targeted McCain repeatedly, failing to unseat him. He also sought to unseat Jeff Flake, a Democratic senator from Arizona.

Mercer’s politics attracted a lot of attention including blowback at Renaissance, where the company said it faced criticism over Mercer’s actions. An employee in a Wall Street Journal article recounted statements Mercer made that prompted backlash. And Renaissance reportedly faced some issues in hiring.

Mercer in late 2018 said as of Jan. 1 of 2018 he would step down as co-CEO at the firm, leaving Peter Brown as CEO. “I do not plan to retire,” Mercer, 71 at the time, wrote in an email, “but I do plan to relinquish my management responsibilities.”

Mercer said he “will continue with the firm as a member of its technical staff, focusing on the research work that I find most fulfilling.”

Tax Trouble

In 2014, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in an inquiry into possible tax evasion settled on Renaissance Technologies’ use of “basket options.” Renaissance, the IRS and the committee said, had improperly classified thousands of short-term trades as long-term trades. Taxes in the case, which would eventually cover 2005 to 2015, should have been 29 percent not 20 percent.

Renaissance said it only took out money at the end of the year, so trades should be treated as a long-term gains. The committee and the IRS said individual trades incurred tax lability.

“We believe that the tax treatment for the option transactions being reviewed by the (Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations) is appropriate under current law,” Renaissance said in a written statement in 2014. “These options provide Renaissance with substantial business benefits regardless of their duration.”

Others saw Renaissance as disguising short-term trades as long-term trades. A trade is a trade is a trade, they said.

“We are very concerned about the idea that Renaissance Technologies could dodge a $7 billion tax judgment,” Michael Kink, an attorney and executive director of Strong Economy For All Coalition, said earlier. “We raised the danger of being able to buy influence with the federal government in order to get rid of a huge potential tax liability.”

The IRS issued guidance in 2015, clarifying any questions. Renaissance, argued that, in the absence of that clear guidance, it should be allowed to treat its trades as it chose for tax purposes. The result was a nearly $7 billion question.

A medical school by any other name

Although Renaissance is in many ways sought to be more low profile after Mercer stepped down and the $7 billion tax case continued to simmer, it attracted attention for other reasons. Jim and Marilyn Simons through their foundation donated hundreds of millions to Stony Brook University, which honored him and has called him, if not a savior, its biggest donor.

Renaissance was about to get its own medical school. The Stony Brook University Council, an advisory board to the university, in October 2017, approved naming Stony Brook University’s medical school in honor of Renaissance Technologies.

The Board by a vote of seven to one supported the renaming the school the Renaissance School of Medicine, with one vote opposed, by Karen Wishnia, the only student representative in the group.

Why did she vote, “No?” She was the treasurer of the Graduate Student Organization and a doctoral student in the department of Art History and Criticism. Renaissance had become controversial and naming a school in its honor carried risks as well as some concerns.

Jim and Marilyn Simons were the school’s biggest donors, but the resolution would not name the school directly for them.

They through their foundation in 2011 donated what the school called an “historical $150 million to Stony Brook University.” That led to $50 million in donations from others for what the school called “a total Simons effect of $200 million.”

“Stony Brook is an outstanding public university, offering a wonderful education at reasonable cost to thousands of young people,” Simons was quoted as saying regarding the decision to donate $150 million.

Stony Brook University already was home to the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics. Newsday in 2014 reported Jim and Marilyn Simons pledged $25 million to The Simons Center for Geometry and Physics, to total $105 million they provided to that center.

Renaissance had become famous for its executives’ involvement in politics. And there was always the question as to whether donations, in some way, were meant to produce good will, potentially in the face of that $7 billion tax case, which swam out in the waters like a shark.

Renaissance had provided massive support to Stony Brook: The school wanted to reward it. Simons was a supporter of Democratic candidates. Co-CEO Robert Mercer, possibly Trump’s biggest and first big supporter, was sometimes credited with helping turn Trump from candidate into president. Stony Brook was naming the school for a fund whose executives supported it. Still, some worried that Renaissance brought baggage with it – and the $7 billion tax bill was at best a small part of that.

Settling the case

The protestors who had rallied outside of Renaissance headquarters probably would have been among the most surprised when Renaissance settled the case. Renaissance CEO Peter Brown revealed a settlement with the IRS in a letter to investors widely reported to be about $6.8 billion.

Simons, Mercer, Brown and several Renaissance board members will pay much of the bill with some help from Medallion investors.

Brown wrote that the Board chose to settle “rather than risking a worse outcome, including harsher terms and penalties, that could result from litigation.”

The company had been seeking to overturn the case in talks with IRS’s Office of Appeals. They argued they did not structure trades to avoid taxes. Still, a failure to resolve a case typically leads to U.S. Tax Court or other federal courts.

The IRS in 2015 indicated that hedge funds using “basket options” had to report them on their tax returns and correct past returns. The argument that the IRS should let bygones be bygones went counter to that.

Renaissance faced some other recent headwinds, in terms of performance. According to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, The Renaissance Institutional Diversified Global Equities Fund lost 22.62 for the year as of December 25, 2020, while the Renaissance Institutional Diversified Alpha lost 33.58 percent.

“Although recent performance has been terrible and worse than prior performance would have suggested was likely for 2020,” Renaissance said in a statement obtained by Bloomberg, Renaissance said it “anticipates that in track records as long as ours, some risk-return ratios every bit as bad as the ones we are now seeing are not shocking.”

Sign up for Long Island Press’ email newsletters here. Sign up for home delivery of Long Island Press here. Sign up for discounts by becoming a Long Island Press community partner here.