Stony Brook Student Pushes New York Politicians, Educators to Do More to Prevent Youth Suicide

America’s young people are struggling. It’s been well documented that suicides and attempts at self-harm among preadolescents, teens and young adults have increased at an alarming rate over the last two decades.

According to the American Psychological Association, the suicide rate among American youths aged 10 to 24 rose from 6.8 cases per 100,000 people to 10.7 cases per 100,000 people between the years 2000 and 2018. And while the overall suicide rate declined in 2019 and 2020, it rose nearly back to its peak again in 2021 — a year that saw suicide become the second leading cause of death for children aged 10 to 14. Additionally, a Centers for Disease Control study notes that an increasing number of students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness in 2021, including 57% of girls — up from 36 percent in 2011 — 29% of boys and 69% of LGBTQ+ students.

The mental health crisis among America’s youth has reached an inflection point — and state and local governments and educational institutions have vital roles to play in helping to address those struggles. But when it comes to suicide prevention programs, it’s easy to argue that New York State is behind the curve. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention notes that at least 37 U.S. states currently require K-12 schools to develop uniform suicide prevention and intervention standards. At least 20 states also require colleges and universities to adopt some form of student suicide prevention policy. New York is not among those states in either category.

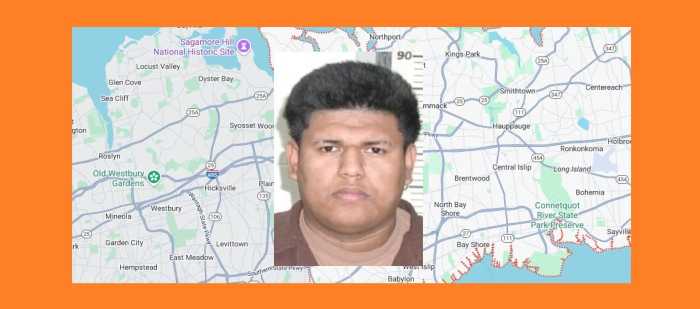

Vignesh Subramanian, a Stony Brook University senior, is looking to change that. In 2022, Subramanian founded One More Option (OMO), a student-led, New York-based policy advocacy organization that works to expand children’s access to mental health and crisis resources and services. OMO’s efforts center on pushing state-level legislation to remove barriers to healthcare access, bolster safety nets and intervention strategies, and expand institutional accommodations and treatment options for struggling youth. The genesis of Subramian’s advocacy, at least in part, can be traced back to his middle school years in Wilton, Connecticut.

“I lost a close friend of mine to suicide when I was in eighth grade,” he explains. “And during the pandemic in the fall of 2020, another student [died by] suicide, and that student was my younger brother’s best friend. These repeated traumatic events kind of shook the town. And they caused a lot of us to look at ways that the state could help us address mental health issues.”

Working with student governments and advocacy groups across the state, Subramanian is currently leading the effort to get a key piece of suicide prevention legislation passed in New York State. And his organization is advocating for a number of specific changes designed to dramatically increase the original bill’s effectiveness.

The Student Suicide Prevention Act (SSPA) was previously introduced in both the 2019-2020 and 2021-2022 legislative sessions, but stalled in committee both times. In January 2023, it was reintroduced by state Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal (D-Manhattan) and Assemblymember Daniel O’Donnell (D-Manhattan).

The legislation appears to have at least some bipartisan support. State Sen. Anthony Palumbo (R-New Suffolk) joined Democrats in sponsoring the reintroduced bill. Subramanian notes that after securing support for his organization’s requested changes in both houses of the state government, the next step is getting buy-in from Gov. Kathy Hochul.

“We’re still inviting schools to join our coalition,” Subramanian explains. “By mid-February, we’re planning to reach out to Governor Hochul’s office requesting her public support for the legislation.”

Subramanian’s growing coalition currently consists of more than 20 collegiate governments, including Stony Brook, Hofstra, Adelphi, LIU Post, Farmingdale, and Molloy on Long Island.

The coalition is calling for a series of key changes to the SSPA. If enacted as originally written, the SSPA would require K-12 public schools to develop policies and guidelines on how staff should respond to students in suicidal crisis. But the additions to the bill go much further:

One of the coalition’s most important proposed changes requires all New York State colleges and universities to join K-12 schools in establishing a uniform statewide standard advising faculty on how to address students exhibiting suicidal behavior and tendencies.

In early January, Subramanian and representatives from his coalition met with Hoylman-Sigal’s office to finalize changes to the bill, he says. The coalition is continuing to work to build support for the changes among Long Island and state lawmakers as the new legislative session begins.

In addition to extending policy requirements beyond K-12 schools to include state colleges and universities, Subramanian’s changes also include provisions expanding the scope of the bill’s mandates to cover nonpublic schools and address other at-risk student populations, he says. These proposed additions would change the bill’s definition of educational institutions to include charter, private, and independent schools, compelling them to develop suicide prevention policies just as public schools would be required to do.

The additions also list racial and ethnic minority groups alongside others named in the bill (including LGBTQ+ children and children with chronic mental health conditions) who are recognized to be at greater risk of suicide and therefore require more specialized resources.

Also vital are provisions increasing access to, and visibility of, crisis resources and services for all students. Subramanian points out that at least 21 U.S. states have taken measures to place such resources within easy reach, requiring information about mental health conditions to be included in student orientation sessions, specialized curricula and school websites.

Modeling laws passed in Illinois, New Jersey, South Carolina and elsewhere, further enhancements to the bill include requiring college staff and resident assistants to be trained in mental health aid, and requiring screening tools, outreach strategies and peer support programs to be developed for students enrolled at all public state colleges and universities.

Before diving headfirst into suicide prevention advocacy in New York State, Subramanian had already notched some legislative wins in Connecticut. (He now lives full time in New York, splitting his time between Elmhurst, Queens and Long Island, where he works as an emergency medical technician as he completes his senior year at Stony Brook.)

In 2021, he personally drafted a section of enacted legislation that eliminated the state’s cap on the number of outpatient counseling sessions minors may seek without parental consent, he says, adding that his contribution to the legislation also established “mental health days” for Connecticut’s 500,000 K-12 students.

As the enhanced version of the SSPA winds its way through the legislative labyrinth of New York State politics, Subramanian is closely tracking the bill’s future — and thinking about his own.

Graduating this spring with a dual major in psychology and biology, he plans to take a gap year, continuing his work as both a suicide prevention advocate and an EMT.

Given Subramanian’s proven effectiveness as an activist and advocate, he’d probably make a fine politician. But he has a different calling. This spring, he’ll begin applying to medical schools with the goal of ultimately becoming a surgeon.

“As an EMT, I’ve responded to a lot of young people in a suicidal crisis,” he notes. “And I’ve had plenty of exposure to trauma. So trauma surgery is something I think I’d like to pursue.”

Consistent with the views of many mental health professionals, Subramanian believes that the spike in suicides and ennui among his generation is at least partially attributable to environmental factors.

“With school shootings and ongoing violence that doesn’t seem to be tamped down by anything, as well as the cost-of-living crisis and issues around the viability of our futures … a lot of these things come together and place what I would say is an unprecedented level of stress on today’s youth,” he says. “This is the environment in which suicides happen.”

To effect meaningful change, Subramanian recognizes the power of advocacy among people in his age group.

“”I founded this initiative in response to public warnings issued by the U.S. Surgeon General and coalitions of medical groups that declared the pediatric mental health crisis a national emergency,” ” he notes. “This is something that we feel the effects of very acutely — and something that I believe should be dealt with by a youth-led, youth-centric effort.”