Hundreds of gallons of natural gas spilled into the Gulf of Mexico early last month when oil rig workers lost control of a well they were trying to plug, unleashing a four-mile sheen off the Louisiana coast still recovering from BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, the worst oil spill in U.S. history.

That July 9 slick escaped hours before a Long Beach public hearing where opponents spoke out against a proposed liquid natural gas deepwater port dubbed Port Ambrose, an LNG import facility named for the New York shipping channel. It would be anchored in more than 100 feet of water about 20 miles south of Long Island in the Atlantic Ocean.

Although the since-sealed Gulf well and proposed LI port are more than 1,000 miles apart, the latest spill fuels fears—or what industry proponents called “environmental emotionalism”—among critics opposed to the possibility of LNG supertankers making up to 45 deliveries annually off Long Island.

“Bottom line is that natural gas is dangerous,” says Lindsay McNamara, a spokeswoman for the nonprofit New Jersey-based Clean Ocean Action, citing the new spill—one of two in the Gulf last month—that came days after the latest explosion at a natural gas drilling well, this time in West Virginia.

Environmental problems stemming from the possibility of such leaks were at the top of the list of concerns of the 90 speakers at the LI hearing and another the following day in Edison, N.J., where memories of a 1994 natural gas pipeline explosion still linger.

The U.S. Coast Guard and Maritime Administration will have to decide whether to grant the LNG deepwater import facility license application by Liberty Natural Gas, a five-year-old company trying again after New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie vetoed their previously proposed LNG port that would have been closer to the Jersey Shore. This time, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo also has a say.

But it isn’t just fears of another Deepwater Horizon-scale disaster killing marine life, poisoning water and scaring away tourists that worry opponents. Critics also say that such facilities are targets for terrorism, that the port would force fishermen and a proposed wind farm from the same offshore area, and they argue, it’s a “Trojan horse” to export natural gas from the boom in hydraulic fracturing, the controversial drilling practice know as fracking—linking Port Ambrose to the debate over whether the practice should be allowed in upstate New York.

“There is no truth to the claim,” said Roger Whelan, Liberty’s CEO, through a spokesman. “The project permits would not allow exports to occur through the facility.”

The port, which aims to go online in December 2015, is one of one of four proposed import terminals and 23 export terminals being proposed nationwide as of June, according to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. There are currently 10 LNG import facilities and one such export facility nationwide.

The entire tri-state area is watching closely because the environmental, economic and national security concerns being hashed out are similar to a failed project, the Long Island Sound LNG terminal dubbed Broadwater vetoed in 2008 by then-Gov. David Patterson.

SHELL GAMES

Liberty Natural Gas noted in its 1,500-page proposal published in the Federal Register four weeks prior to the public meetings that it is abiding by laws forbidding it from lobbying federal lawmakers or issuing construction contracts.

But that didn’t stop them from contracting a small army of lobbyists to push their cause in New York City and Albany. Whelan signed three $120,000 contracts—a total of $360,000—to lobby New York lawmakers, three times as many lobbying firms he hired in New Jersey, disclosure reports for both states show.

“The natural gas industry has immense political sway,” said Chris Herb, president of the Connecticut Energy Marketers Association, pointing to the 2005 so-called “Halliburton Loophole” that exempts fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act, shepherded into law by former Vice President Dick Cheney.

To lobby New Jersey officials in 2011, Liberty hired Princeton-based Capital Public Affairs.

Liberty hired New Jersey-based Bolton-St. Johns, LLC, for “legislative and regulatory representation” in New York from October 2011 through September 2012, the same month the company met with Long Island Association officials 10 days before submitting its intent to file its latest application.

In March 2012, Liberty hired another New Jersey-based lobbyist, Matthew Greller, to lobby New York through April, when Liberty replaced him with two dozen lobbyists from Albany-based Wilson, Elser, Moskowitz, Edelman & Dicker, LLP, through next spring.

Financially backing Liberty is Toronto-based hedge fund West Face Capital via West Face Long Term Opportunities Global Master L.P., a Cayman Islands-based investment fund. Liberty, incorporated in Delaware before setting up a New Jersey office for its first port try, now lists an address in Manhattan.

A spokeswoman for Cuomo said he is “monitoring the situation.” Christie’s office did not return a call for comment.

FRACK OFF

The Coast Guard and Maritime Administration held the back-to-back public scoping meetings so concerned citizens could suggest issues to be investigated in the environmental impact study for the proposed port.

One issue the panel had heard enough of halfway through the proceedings. After listening to LI opponents urge the agencies to study the environmental impact of upstate fracking based on the possibility of the port being an export conduit, one official cautioned New Jersey speakers against making the same request.

“There was what I can only describe as a mischaracterization of the licensing…of this particular project,” said Keith Lesnick, director of the Maritime Administration’s office of deepwater port licensing, in Edison before reading part of his agency’s letter to anti-fracking group Catskills Residents for Safe Energy, emphasizing only import impacts will be studied.

But the Coast Guard and Liberty maintain that before Port Ambrose—assuming it’s permitted—could switch to exporting from importing, it would trigger a new license application process that would “likely” include more public hearings.

Sean Dixon, an attorney with Clean Ocean Action, argues that the claim omits the fact that federal law doesn’t always require public hearings for deepwater port license amendments. He points to the process behind Port Neptune LNG facility off Boston suspending operations based on lack of demand after the Ambrose hearings.

“This suspension was carried out in exactly the same way [the Maritime Administration] could amend the Liberty LNG license to allow exports,” he said. “This suspension was done as a license amendment, and had zero public input, zero comment opportunity and no mention of environmental review.”

Bruce Ferguson, a Catskills Citizens for Safe Energy advocate who spoke against Port Ambrose in Long Beach, remains suspicious that an export terminal down the Hudson River would only help companies hoping that Cuomo will end a six-year de facto fracking moratorium so they can begin pumping carcinogens into the ground to drill natural gas near Ferguson’s home.

“No one can deny that this terminal would be a potential export facility,” he said. “If there’s no market for imports, it’s going to be used for exports. Therefore it’s only reasonable to assume that all the potential environmental impacts, including the impacts of fracking, be evaluated before hundreds of millions are spent on this project.”

GASONOMICS

Since the boom in fracking in the nation’s subterranean shale formations has flooded the domestic market with natural gas, the question of why New York City and LI would need to import higher-priced gas from the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago has come up repeatedly.

Liberty’s answer is that prices for natural gas—which fuels a dozen power generating facilities on LI and heats 43 percent of LI homes and businesses—spike during peak demand months of summer, but mostly winter, because of bottlenecks in the Iroquois and Transcontinental pipelines serving LI. Port Ambrose would link to the latter two miles off Atlantic Beach after a 22-mile, 26-inch pipeline was built.

“Despite an abundant resource of natural gas within the United States, building new pipeline infrastructure across New York City is extremely difficult,” Liberty CEO Whelan said. “A mobile ship-based system such as ours costs considerably less and can be put to work elsewhere in our system during non-winter months.”

Howard Rogers, director of the Natural Gas Research Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, agrees.

“The shale gas boom…has really negated the requirement for the U.S. to import LNG, but with certain specific exceptions,” he says. “There is a gas demand which can’t be met easily by the existing pipeline infrastructure and those are the areas where LNG is still imported.”

As far as the possibility of the import-to-export switch, he noted that there are several multi-million-dollar LNG tankers currently under construction that would for the first time have the capacity to liquefy natural gas from the gaseous state in which it’s piped.

Currently, on-shore facilities chill natural gas to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit so it’s condensed enough to be shipped long distance in cryogenic tankers that upon delivery re-gassify the LNG, which is mostly methane.

Höegh, Liberty’s tanker contractor, is among those developing ships designed to liquefy natural gas onboard. But, even if Port Ambrose cleared hurdles to export, such tankers are being eyed for harder-to-reach natural gas fields, Rogers says.

Port Ambrose would accept an expected annual average of 400 million standard cubic feet per day of natural gas. National Grid sent 197 billion cubic feet of natural gas between July 2012 and June 2013 to LI, according to the utility, which a spokeswoman says is not taking a position on the proposed port.

A Long Island Power Authority spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

Herb, of the Connecticut Energy Marketers Association, isn’t buying it, saying he “would not put it past them to do a bait-and-switch.”

“Natural gas companies are in business to make money,” he says. “I would not be surprised if the real purpose of the construction was not to stabilize prices, but to maximize profits.”

Kevin Rooney of the Long Island Home Heating Oil Association, no fan of National Grid stealing his customers, notes that if the Department of Energy approves LNG exports to non-free trade agreement nations, more demand will cause a domestic natural gas prices spike.

“Once we become the biggest gas exporter in the world, you’re going to see the same thing happen in their market that’s happened in ours,” he says, referring to oil prices subject to the mercy of Wall Street and foreign powers. “They are setting themselves up for a rapid escalation in prices.”

Congress is studying the same issue.

“Five years ago companies were building terminals to import natural gas at the cost of billions of dollars because analysts believed that the U.S. was gonna need natural gas from overseas,” said Rep. Ted Poe (R-Texas) in an April hearing on exporting LNG. “Today that scenario has changed 180 degrees.”

SHIPWRECK

The possibility of encroaching on Long Island’s fishing grounds was bad enough, but worse still is the prospect of a terrorist attack on an LNG tanker 30 miles from the mouth of New York Harbor—and not much farther from Ground Zero, opponents say.

Al-Qaeda specifically cited LNG terminals as a desirable target for supply disruptions and “because an attack could result in a massive fire that could potentially kill scores of people,” according to a 2006 Council on Foreign Relations report citing homeland security experts.

“Another scenario in the report involves terrorists taking control of an LNG tanker, sailing into a major population center such as New York City and detonating the cargo,” said Klaus Rittenbach, a former Department of Defense Information Systems Agency official from Freehold, citing that report in Edison.

When asked about plans to protect the tankers from a hijacking or a U.S.S. Cole-style attack, in which a smaller boat detonates next to the ship in an attempt to pierce the hull and explode the flammable cargo, Liberty was vague.

“The U.S. Coast Guard will review all safety and security issues as part of the application review and will conduct a detailed risk assessment,” Whelan said. “This assessment will be used to develop a security plan that will be approved and overseen by the Coast Guard, which will govern operations at the port.”

When the same question was posed to the service, Charles Rowe, a spokesman for the Coast Guard—the only military branch that falls under the Department of Homeland Security—said that which ships get escorts is decided in real time.

“It depends upon the threat at any given moment,” he says. “That’s something that is continually evaluated and revaluated and decisions are made quite literally on a daily basis.”

Cynthia Kouril, a former federal prosecutor who investigated environmental crimes, urges against taking the risk.

“You do not put something that dangerous, that explosive, next to one of the largest population centers in the world … a population center that is both a well-known target of terror attacks….and in the path of hurricanes,” she said. “This project should fail at the earliest possible stage in the application process because the flaws in it are so self-evident.”

GAS PANNED

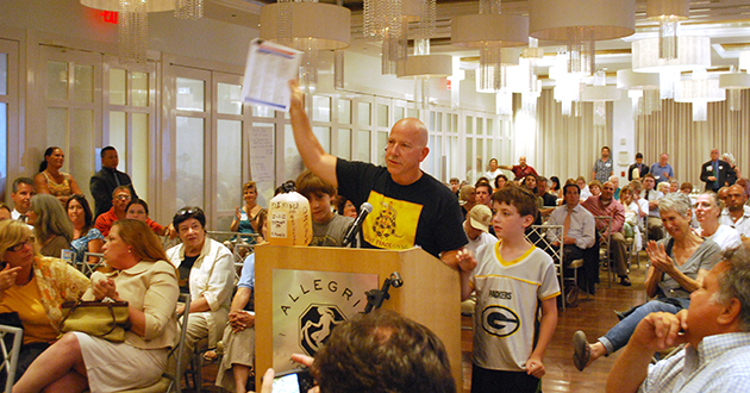

As much as the hearings unified upstate and downstate environmental advocates with those from across state lines, regional rivalries were also on full display—most notably at the Long Beach hearing at The Allegria Hotel, which with 300 in attendance was twice as packed and far rowdier than the New Jersey hearing.

Thirty five LI speakers were opposed versus four union members in favor, including Roger Clayman, executive director of the Long Island Federation of Labor, who supported the jobs the project would create. Time ran out before another 35 speakers had their turn. In the tamer New Jersey hearing, 46 were opposed, three supported Port Ambrose and two—perhaps in a nod to the town’s namesake, inventor Thomas Edison—urged federal officials to decide on the facts alone.

“Gov. Christie already vetoed this,” said Jessica Roff of Brooklyn, referring to Liberty’s prior proposal. “Since when did New York become the dumping ground for New Jersey?”

Before one union member told the opponents to “go to hell,” another from New Jersey who favored the proposal was booed when he told the Long Beach crowd—worried that more fossil fuels will increase climate change and strengthen hurricanes—that their Sandy damage wasn’t as bad as the Jersey Shore’s.

Perhaps traveling the farthest distance for the LI hearing was Craig Stevens, who lives near Dimock, Penn., a small town that became well-known since residents fought fracking companies they say poisoned their drinking water.

“It’s not about gas, it’s about people,” says Stevens, who brandished a gallon container full of yellow liquid dubbed “Dimock Lemonade” or “Cabot Kool Aide,” after the oil and gas company. His trip to LI was just the latest in his continuing “scare the hell out of everyone tour.”

Adrienne Esposito, executive director of Farmingdale-based Citizens Campaign for the Environment, was especially riled up about the proposed port overlapping with the area of interest for LI’s latest off-shore wind farm proposal.

“We find it…ironic, but also insulting and alarming that we are having this hearing here, in the great city of Long Beach,” she said. “Because nobody knows better than the people of Long Beach the impacts of climate change. The life-altering impacts, the economic, the financial, the emotional devastating impacts of climate change. We know what it’s like to lose it all and yet we’re having a community discussion about shackling ourselves for another 30 years to the damn fossil fuels. No! We want renewable energy, we deserve that. We can’t lose it all again and your policies need to change!”

Members of the public wishing to comment on the Port Ambrose proposal can do so through Aug. 22, a deadline that may be extended.

—With additional reporting by Rebecca Melnitsky