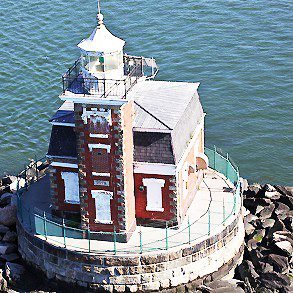

There were no promises that it would be easy—and no one has ever said that the project, that could cost more than $4 million dollars, could be done quickly—but frustration was clearly evident at last week’s meeting of the Stepping Stones Lighthouse Restoration Committee.

There were no promises that it would be easy—and no one has ever said that the project, that could cost more than $4 million dollars, could be done quickly—but frustration was clearly evident at last week’s meeting of the Stepping Stones Lighthouse Restoration Committee.

Committee members voiced various concerns over the difficulty in raising funds, officials not being available for restoration meetings, not returning calls or answering emails, and the sluggish progress of the project in general.

But last week’s meeting did end on a high note with the scheduling of a Sept. 25 trip from the dock at Steppingstone Park to the lighthouse itself.

As many maritime experts have already given their advice and pledged their time, experience, personnel, equipment and even some funds for the project, committee members seemed confident that the trip would attract those experts, as well as local officials and possible donors.

A member of the committee has volunteered a 65-foot boat to be used for the trip that would give participants a close-up view of the poor condition of the lighthouse and dramatically demonstrate the need to restore it.

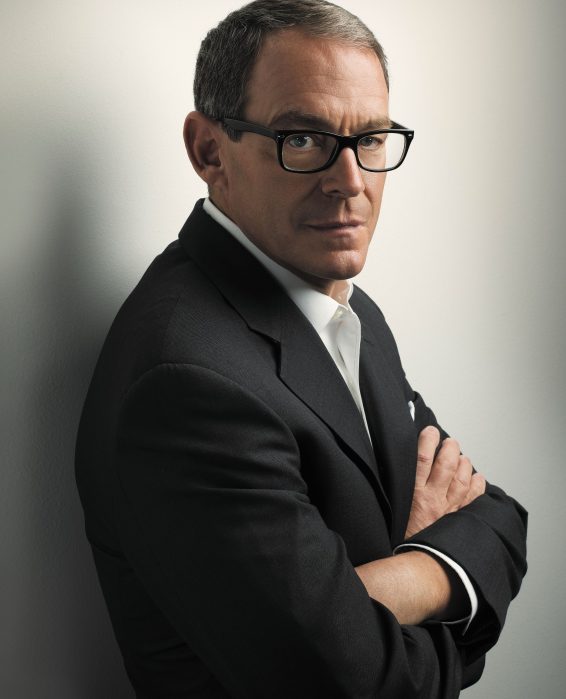

Speaking after the meeting, committee chairperson Bob Lincoln (also a Park District Commissioner) was energized by the scheduling. “We need to take this whole project to a new level and I think we broke some ice here this evening with the trip,” he said.

Earlier, Lincoln spoke about the fundraising difficulties that the committee has experienced so far. Referring to previous efforts involving the selling of T-shirts and contributions from students at the John F. Kennedy School, who raised more than $800. “All these things have generated revenue,” he said, “but it doesn’t generate thousands. It generates hundreds. We need to start thinking about thousands.”

The initial goal of raising $50,000, set last August, has not been reached. To date, a little more than $20,000 has been raised.

Great Neck Historical Society President Alice Kasten was quick to point out that the contributions raised so far have “raised consciousness” about the restoration.

“Absolutely,” Lincoln agreed.

He spoke of the need to impress people, especially potential big donors, of the historical significance of the lighthouse. “If we really want to get into the big donors, we’ve got to show them that this is more than just some people trying to fix up some nice old building.”

“If you think of the lighthouse

as a hub (of a wheel) and that the spokes reach out in all directions to all the maritime history of western Long Island Sound, it’s phenomenal,” he explained.

“City Island, Port Washington, both Hempstead Harbor and Manhasset Bay, that’s where the sand was mined to be used for the concrete to build New York City,” he continued. “Every barge load went by the lighthouse. If we really want to reach into the pockets of these really big donors, we really need to involve them and grab their interest.”

Also present at the meeting was North Hempstead Grants Coordinator Tom Devaney, who said he hoped that the two grants he was working on would eventually be successful.

The committee to save the deteriorating lighthouse, which was built in the 1870s to warn ships of shoal and rocks in Long Island Sound, was established a little more than a year ago as a branch of the Historical Society. The lighthouse is in shallow water less than a mile from the Great Neck peninsula.

Lincoln has often expressed his fears that the lighthouse would eventually be torn down and be replaced by “a light blinking on a pole.” The group is dedicated toward making sure that the lighthouse remains.