By Kevin Deutsch

Cesar Hernandez felt a bone in his cheek crack as the Brentwood gangsters pummeled his face, the sound reminding him of a “branch breaking, like a crunch.”

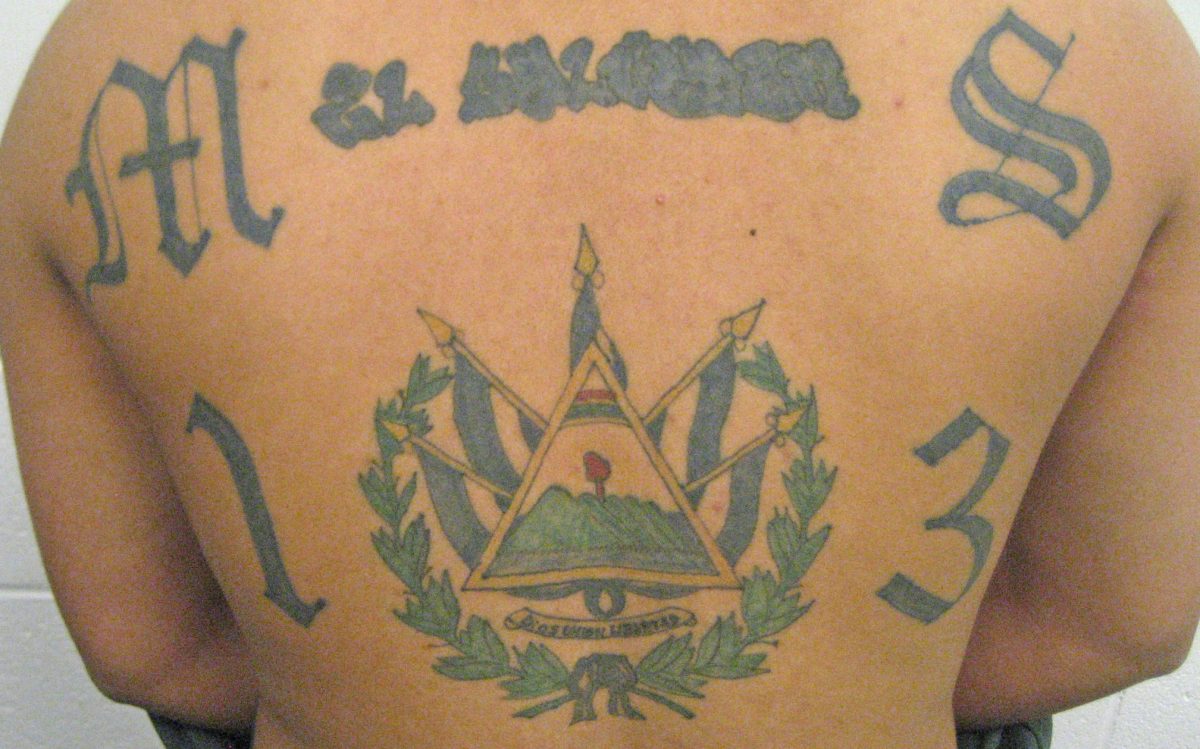

It was a rainy afternoon in June 2013, and Hernandez, then 16, had just been attacked by four members of one of Long Island’s most notorious MS-13 sets: The Brentwood Locos Salvatruchas, also known as B.L.S.

The reason for the “beatdown,” these gang members told him: Hernandez’s older brother had been spotted selling marijuana within MS-13’s sprawling territory. Since they’d been unable to track his brother down and retaliate for the territorial infraction, it was Cesar, they said, who’d have to pay the price.

“I didn’t get a chance to say anything to them,” Hernandez recalled Wednesday, sharing his account of the gang assault with a reporter for the first time. “They jumped me when I was walking home and… just started pounding on me.”

The blows rained down on Hernandez’s face, head, chest, arms, and ribs, leaving him with several broken bones in his face, two black eyes, and a handful of cracked ribs, he says. Hernandez was treated at a local hospital, and police took a report on the incident. The gang members responsible for the assault all ended up in jail or prison within a year, locked up on a host of weapons, drug, and assault charges unrelated to Hernandez’s case, he recalls.

But it wasn’t long before those gangsters were replaced by more aggressive members—young men who’d risen rapidly through the B.L.S. hierarchy, and were anxious to make a name for themselves in the Long Island underworld.

“They got too many [members] for the police to get rid of them completely,” Hernandez says of B.L.S., adding that the set’s members have long been involved in a small number of heroin, marijuana, and cocaine operations in Brentwood and surrounding areas. In addition, several of the gang’s leaders oversee protection rackets that extort illegal immigrants and off-the-books workers in the area. They also sell stolen cars, commit robberies, and fence stolen goods to fund their criminal enterprises, authorities and victims say.

“If you don’t pay them, they beat on you, they cut you, they come after your people,” says Wilfredo Ortiz, 43, a Brentwood cook who says his food truck was vandalized by MS-13 members after he refused to pay them protection money in 2014.

“They took away our family’s livelihood,” says Ortiz’s sister, Yvette. “They want to control people. They want to control through fear.”

“We can’t be silent about it anymore,” she adds.

Interviews this week with more than a dozen Brentwood residents who say they’ve had run-ins with B.L.S. highlight the extent to which members of MS-13 in general, and B.L.S. in particular, have ingrained themselves in the fabric of life in this community—and created a climate of fear.

Brentwood residents’ fear is for good reason. The community was ranked as having the highest concentration of gang members in the county, according to a 2012 report by the Suffolk County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (SCCJCC). The study counted 4,103 gang members concentrated in neighborhoods with high poverty rates.

MS-13 boasts numerous sets across LI, police officials say, but nowhere are the gang’s ranks larger—or its members more brazen—than in Suffolk County, which by some estimates has been home to more than 1,000 MS-13 members over the past decade, according to a retired law enforcement official with first-hand knowledge of anti-gang operations on the Island. That’s double the number of MS-13 members the SCCJCC study tallied.

Adding to the problem in Brentwood are rival gangs such as the Bloods, Crips, and Salvadorans With Pride, whose members are locked in perpetual conflict with MS-13. Violence between the groups can break out for any number of reasons, ranging from an incident of perceived disrespect to an improper incursion onto another gang’s turf, authorities say.

B.L.S. is considered particularly dangerous because of its routine targeting not just of rival gangs, but of civilians, suspected police informants, and even its own members.

“If they think you might talk to the cops, to anybody with a badge, you’re not going to be around, believe me,” says one Brentwood 17-year-old, who spoke through a translator and asked to remain anonymous out of fear MS-13 members would harm him. “Even if you’ve been in [MS-13] for a long time, if you go against the rules or they don’t trust you…” Here, the teenager mimes cutting his neck. “That’s it.”

The issue of gang violence in Suffolk returned to the spotlight in the past two weeks when police discovered the remains of four teenagers, all of whom authorities suspect may have been victims of gang violence linked to MS-13, sources say.

The bodies of Brentwood High School students Nisa Mickens, 15, and Kayla Cuevas, 16, were badly beaten, police said. In a wooded area about two miles from the elementary school near where the girls were found, police discovered the skeletal remains of 19-year-old Oscar Acosta, who was reported missing under suspicious circumstances in May, and Miguel Moran, 15.

Police have not publicly confirmed that they suspect MS-13 is responsible for all four killings, but the retired law enforcement official with knowledge of local gangs said B.L.S. members are a focus of the probe. An active law enforcement official, also with knowledge of the probe, substantiated that information.

“This is their MO,” the retired official said of B.L.S. “They consider themselves the baddest of the bad.”

Suffolk Police Commissioner Timothy Sini has said authorities are doing “everything in their power” to solve the killings and target local gangs. They also scoured the grounds of Pilgrim State Psychiatric Center this week, which Sini called “doing our due diligence to fully investigate the area for evidence.”

The commissioner put the gangs on notice while touting his department’s enhanced patrols, increased cooperation with the FBI’s Long Island Gang Task Force and having a gang member in federal custody. The crackdown, a host of community meetings on the issue and re-energized community watches are much like the reaction to an even deadlier spate of gang violence in the community seven years ago.

“The only people in Brentwood who have something to fear are the criminals,” Sini said. “And we are going to do everything in our power to bring those accountable to justice.”

For Yvette Ortiz and other locals long accustomed to gang violence, the commissioner’s words have brought little comfort.

“I believe they’re doing everything they can” to stop B.L.S, Ortiz says of law enforcement. “But they’ve [gang members] been here a long time. It’s not going to be so easy.”