The shabbily dressed, wild-eyed man was sitting quietly at a Chock full o’Nuts counter when he suddenly started banging his cup and screaming. Other customers glanced quickly at him and looked away, savvy New Yorkers knowing to avoid eye contact. A few decided it was time to get moving. No big deal. This was 1981 Manhattan. Wackos were an everyday thing.

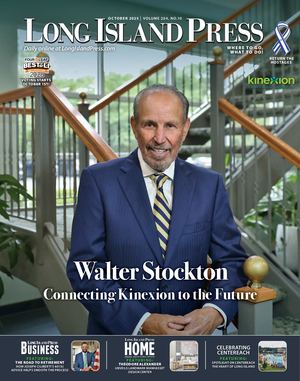

The wacko in this case was Andy Kaufman, a once shy, Jewish kid from Long Island who was then at the top of his stardom, mesmerizing audiences with the oddball characters they loved and the jerks they despised.

Kaufman later described the coffee shop scene to an interviewer, but did it really happen? Or was it just another fantasy from his make-believe world, one more put-on from the master of performance art? The man, as the Los Angeles Times put it, who “may have been the greatest con artist in modern entertainment history.”

(Or not. As David Letterman once said, “Sometimes, when you look Andy in the eyes, you get a feeling somebody else is driving.”)

Either way, audiences remain fascinated by Kaufman’s story, even though it ended abruptly, in 1984, when the comic was 35. Netflix, in fact, has just acquired the rights to Jim & Andy, a new documentary based on the 1999 biopic Man on the Moon, which starred Jim Carrey as Kaufman in a performance Carrey called a “psychotic” experience.

Andy’s Mad Funhouse

Kaufman’s inspirations sprang from what appeared to be a normal, middle-class childhood. Born in New York City in 1949, Kaufman was raised in affluent Great Neck, just another a suburban kid addicted to 1950s television. Cartoons and puppet shows were nourishing fodder for the future performer, who started out “producing” children’s shows from his room and by age 9 was performing at children’s birthday parties with a portable record player and puppets, props that would become part of his grown-up act.

Because he spent so many hours a day alone and staring out the window, or in his room working on his productions, his concerned parents sought psychiatric help for their son.

As he got older, Kaufman continued to soak up material. At Saddle Rock Elementary School, a visit from Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji provided the impetus for Kaufman to learn to play the conga drums. His grandmother took him to Times Square, where he was captivated by the freak show at Hubert’s Museum and Flea Circus, and to Madison Square Garden professional wrestling matches, which inspired him to stage his own in his parents’ basement.

He completed his first novel, The Hollering Mangoo, when he was 16.

At Great Neck North, he was a poor student but a prolific writer of poetry and stories who carried around a copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and hung out in Greenwich Village. After graduating from high school in 1967, he drove delivery trucks and drank heavily for a year. In 1968, he went to Boston to major in TV and radio production at Grahm Junior College, where he created and starred in Uncle Andy’s Funhouse on a closed-circuit campus TV station and performed at coffee houses. After graduating from college in 1971, he landed gigs at local New York clubs and restaurants, where he was spotted by Budd Friedman, owner of the Improvisation Comedy Club, the famed Improv.

“I am not a comic”

The irreverent comedians of the early 1970s – Robin Williams, Billy Crystal, Larry David, Richard Lewis, Jerry Seinfeld – startled audiences with bold, often manic routines. But Kaufman was the antithesis of the joke-tellers who delivered the punch line then waited a beat for the laughter.

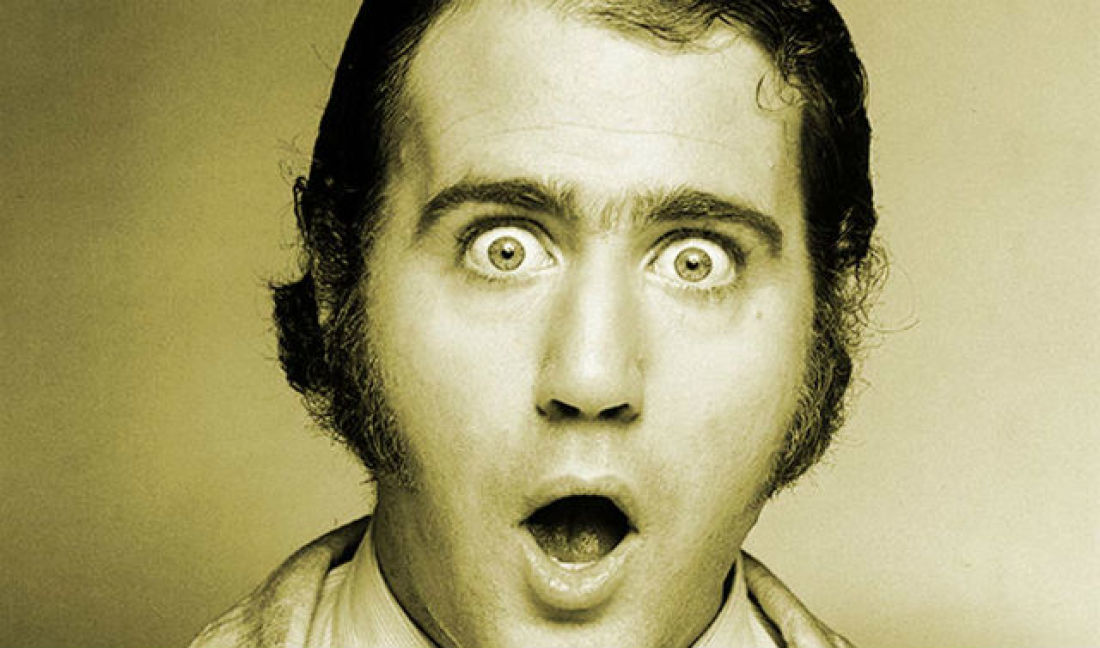

Affecting an English accent, he read aloud from The Great Gatsby until the audience booed and left, or simply napped in a sleeping bag. Creating material he would later become famous for, Kaufman played a phonograph record of the Mighty Mouse theme song, staring silently with bulging eyes until the chorus, when he would raise his hand and confidently lip-sync, “Here I Come to Save the Day.”

And then there was the gibberish-speaking “Foreign Man,” who would babble indecipherably in an excited, high-pitched voice that he was from the imaginary island of Caspiar, and then do impersonations.

That bit got Kaufman onstage at the Improv and on the 1975 Saturday Night Live debut. Executive Producer Lorne Michaels described Kaufman’s act as “midway between stand-up comedy in the Ed Sullivan Show sense, and performance art, which was just beginning to emerge in the world below Houston Street.”

Legendary writer-comedian Carl Reiner likened Kaufman to “Christo wrapping a mountain” – a character doing the worst possible act ever. Reiner told Rolling Stone that Kaufman was thinking, “The game we’re playing is to see how long you can take it before you bomb me.”

Kaufman, of course, enjoyed the game more than anyone. And if the audience didn’t get it, well, no matter. He wasn’t in it to make people laugh.

Testing reality

His perfect idea for television: A talk show in which the guests argue and start fighting, with one getting sent to a hospital and dying. No one would really get hurt, Kaufman said, but “people would always wonder, ‘What’s real? What’s not?’

“That’s what I do in my act, test how other people deal with reality.”

They didn’t always deal with it well. As Kaufman baited the crowds, some turned hostile, with the comic eventually hiring off-duty cops to break up the fights during shows.

Kaufman’s boorish new character, the chauvinistic, swaggering, washed-up lounge singer Tony Clifton, especially enraged crowds, who pelted him with eggs and fruit, leading the comic to don riot gear and used a protective net.

He created a furor after challenging women to wrestle with him or “go back to the kitchen where you belong,” offering $1,000 to any woman who beat him. He was booted from Saturday Night Live after thousands of angry letters.

This was Kaufman at his peak, with appearances on major networks and series, even a live show at Carnegie Hall, after which he hired buses to take the audience – nearly 3,000 people – out for milk and cookies.

The cast: Foreign Man, a crazed conga drummer, his scarily dead-on Elvis, Tony Clifton, a professional wrestler and a clean-cut, born-again Christian engaged to a gospel singer.

When Taxi ended its five-year run in June 1983, Kaufman was still very much a star, performing for David Letterman, in specials and in films. But by Thanksgiving he was coughing frequently and, shortly thereafter, diagnosed with advanced-stage lung cancer. He died in May 1984. After the funeral in Great Neck, he was buried at Elmont’s Beth David Cemetery.

It is a tribute to Kaufman’s performance art that many people continue to insist he faked his death and that he’s out there, somewhere, alive and well.

That would, indeed, be the ultimate Kaufman act.