From the outside, the suburban Dix Hills home looks like many other ranch-style structures that dot Long Island.

But this modest Candlewood Path house has a distinctive history: In 1964, in the upstairs practice room, homeowner John Coltrane composed his Grammy award-winning album A Love Supreme. The work’s spiritual tone captured the essence of a world protesting war amid the emerging pride of African Americans seeking to honor their heritage and contributions to American culture.

Coltrane’s composition changed the world of jazz forever. But the road to success was an uneven path for the jazz saxophonist, bandleader, and composer, blockaded by the pressures of performing and the ravages of drug addiction.

A QUIET VOLCANO

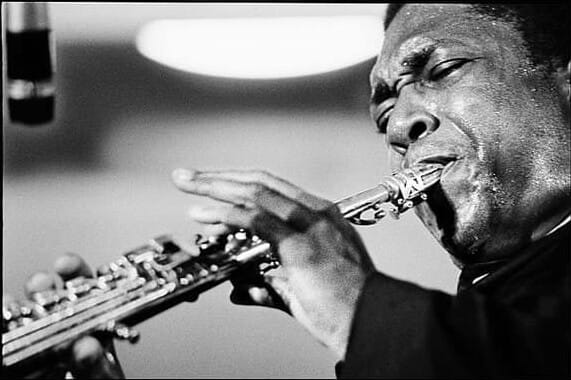

His music was sometimes called “volcanic,” but interviewers called him thoughtful and conscientious. He emphasized the best in others and was noted for being a quiet, gentle man.

His bandmate Miles Davis observed, “…It was like he was possessed when he put that horn in his mouth. He was so passionate — fierce — and yet so quiet and gentle when he wasn’t playing.”

Those bold sounds are still popular after 60-plus years. Coltrane described his motivations by saying, “I’d like to point out to people the divine in a musical language that transcends words. I want to speak to their souls.”

Born in 1926, John William Coltrane grew up listening to the sounds of the many instruments his father played at home in North Carolina and to Count Basie recordings. The youngster picked up the alto saxophone and clarinet and his mother encouraged him to attend music school. He was drafted in 1945 and played with a U.S.Navy band until 1946; in 1947 he switched to tenor sax.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Coltrane (nicknamed “Trane”) performed with the prestigious Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra and as a session musician. “The Duke” Ellington took notice and hired Coltrane. But, like many other “hopheads,” Trane was a drug addict. Ellington fired him.

Miles Davis took a chance and hired Trane to play in his First Great Quintet, but drugs, mainly heroin, intervened; Davis fired and rehired him several times.

JAZZ REHAB

Trane kicked the habit and rehabilitated himself, undergoing a metamorphosis just as jazz was changing. In the late 1950s, the danceable, big-band sound gave way to “bebop,” densely rhythmic improvisation over dissonant chord changes played by small ensembles.

Trane joined pianist Thelonius Monk’s adventurous quartet for six months, developing an increased harmonic and rhythmic sophistication by playing notes simultaneously amid cascading scales, a technique dubbed “sheets of sound” by critic Ira Gitler. After recording under his own name, in 1958 Trane rejoined Davis’s group, emphasizing scale patterns beyond major and minor (“modal jazz”).

Starting in 1960, Trane’s acclaimed quartet focused on mode-based improvisation, experimenting with free jazz and incorporating the spirituality of music of India and Africa.

In 1964, the year Trane moved his family to Dix Hills, he wrote A Love Supreme. As The Guardian noted, “It became a hit with the hippie audience … and … rock guitarists too, notably for the mantra-like chant inspired by Coltrane’s absorption in Indian music and Eastern religious thought.”

The multi-award-winning big seller brought global acclaim. His grueling schedule — practicing 10 hours a day while touring extensively — had a bizarre effect: He’d put his horn down, beat on his chest and scream into the microphone, said his drummer Rashied Ali in 1966 in The Sixties. Ali said Trane was inspired by a Buddhist chant “where you could pound your chest and it would change the sound of your voice. He wanted to get that quiver on the horn.”

Others said that after 1965 Trane was using LSD. Miles Davis claimed that the hallucinogen caused Trane’s death at age 40 in 1967, but the cause of death was listed as liver cancer.

In 2007, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded the musician a special posthumous citation. The home where he spent his final years has been designated a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which will help renovate it as a museum and cultural center. The designation honors a prolific artist who left a formidable legacy — a legacy that will no doubt influence musicians for decades to come.