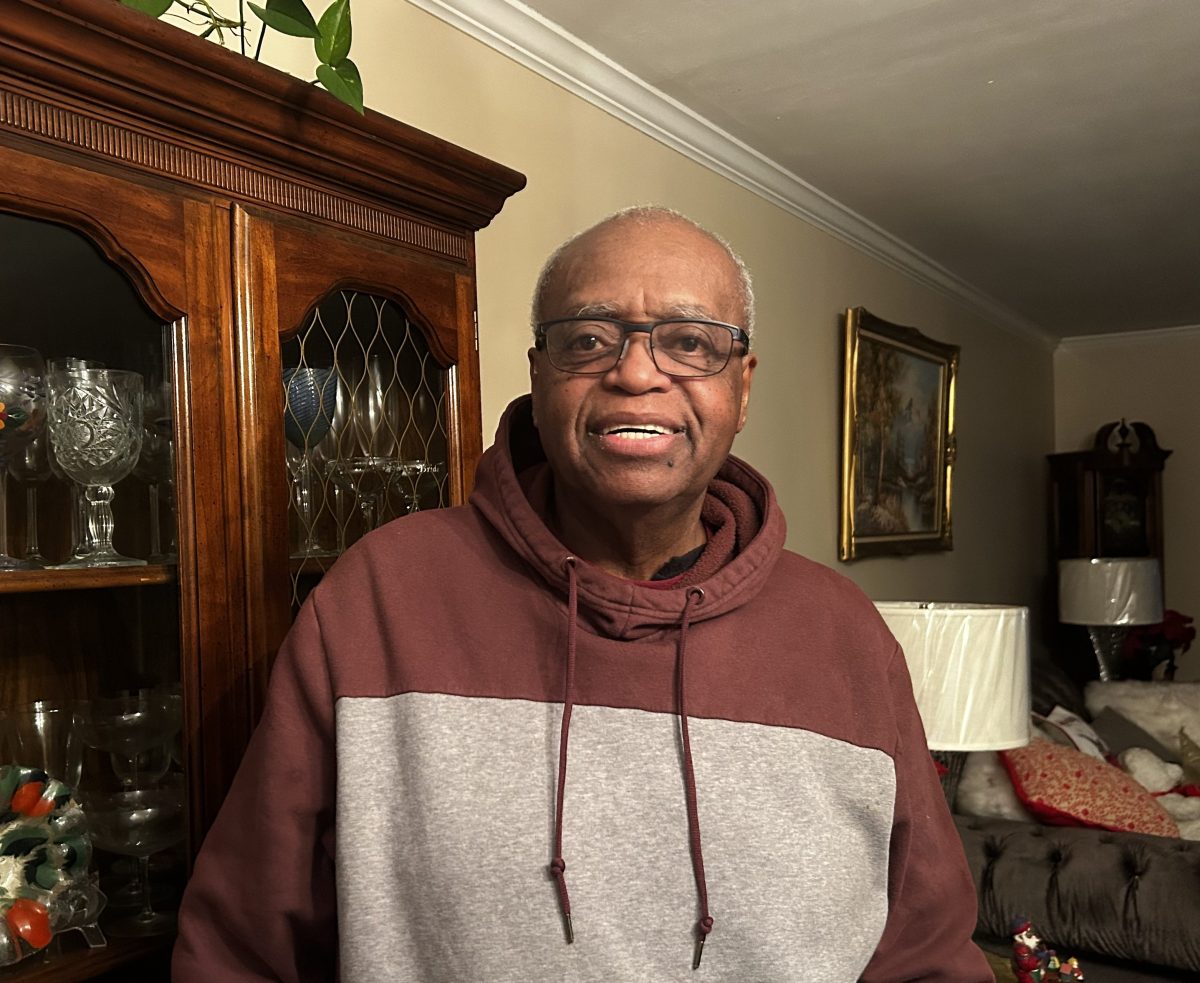

John Mobley said it was time to tell his story as he leaned back in a chair at his kitchen table in Westbury.

“I’ve been thinking about this for quite some time,” Mobley said.

In 1970, Mobley convinced his employers at Publishers Clearing House in Port Washington to allow workers to take off for Martin Luther King’s birthday, 13 years before it was made a national holiday.

Mobley set the scene—he had just gotten back from serving in the Vietnam War.

He had returned from his tour on Friday, and by Monday, he was back to work at his old job as a computer operator for Publishers Clearing House.

“When I came out of the Marines,” Mobley said, “everybody was all over me.”

Mobley said he was a popular person at the company and, on Monday, co-workers were coming up to him to welcome him back.

And as he was welcomed back, he noticed a group of Black workers off to the side.

“When I left [to go to Vietnam], it wasn’t no Black guys working in the computer department.” Mobley said he was the first Black employee at PCH.

“Then January rolled around, and it was a movement for Martin Luther King’s birthday to be a holiday,” Mobley said.

As the workday was coming to a close on Jan. 14, the day before King’s birthday, the other Black workers at the company approached Mobley with a request.

They asked Mobley to go to management and ask for King’s birthday off with pay. His co-workers knew he was hired by the company’s founder and had some clout with the higher-ups, though Mobley said he never thought of it that way.

So Mobley went to pitch the group’s idea to President Lou Kislik and Director of Data Processing Mark Stern.

Mobley said he was nervous. He was 23 years old and fresh out of the Marines, where one was drilled into following orders, not making petitions.

The three negotiated for a couple of hours in the president’s office before reaching a conclusion—they agreed to hold Remembrance Day, where anyone regardless of race could take a day off of their choosing with pay.

Mobley left the office to share the good news with his co-workers. “I couldn’t believe it myself that I did that,” Mobley said.

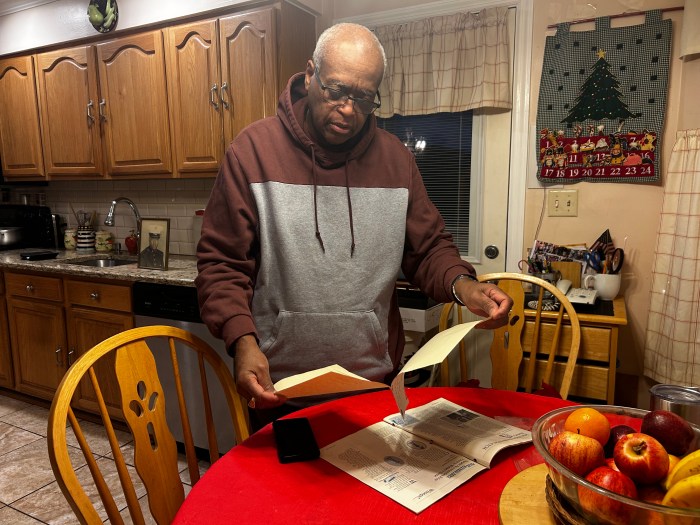

Mobley pulled some papers from a folder as he continued telling his story. Inside was a PCH employee newsletter that laid out the story of how Remembrance Day came to be.

Mobley grew up in Mobile, Ala., during segregation with his mother, father, and seven other siblings. “I was told what bathrooms to go, what fountains to drink. I couldn’t go to restaurants and sit down.”

In 1965, he traveled to Long Island to be with his mother, who had moved to New York for better pay.

In 1966, Mobley accompanied his mother to a job interview in Port Washington. The interview was for a maid position in the home of Harold Mertz, the founder of Publishers Clearing House.

At the end of his mother’s interview, Mertz offered Mobley a job at his company as well. “I’d seen this in movies,” Mobley said, “But I ain’t ever seen this in real life.”

Mobley started in the mailroom, but his interest piqued when he saw computers for the first time. These weren’t the modern computers of today, but rather big, bulky machines that filled the room with spinning tapes.

So Mobley quit his job in the mailroom and trained to be a computer technician, but when the higher-ups at PCH found out, they offered to train him at the company.

Mobley became close with Mertz and his family and would go on to work for the company for the next 33 years.

When Mobley came to Port Washington from segregated Alabama, he said it was a big culture shock. He recalled sipping out of the same bottle as a white friend of his. “In Alabama, that wouldn’t have happened.”

Living in New York was a significant improvement. “It was meant for me to leave,” Mobley said about Alabama.

But it was far from perfect. “Don’t get me wrong. It has not been all roses in New York.”

Mobley was the first Black man living in his apartment building, and he would find out that one of his neighbors was not pleased with his presence.

He said the resident was a veteran with connections in the military and pulled strings to get Mobley drafted.

Usually a very chatty character, Mobley grew quiet when Vietnam came up. “It was a horrible thing…I never wanna see that again.”

When he got back, Mobley was told by the owners of the building he lived in that his neighbor, who had since moved out and bought a house in Port Washington, had tried to get him evicted and drafted.

“Some dark things started coming over my mind,” Mobley said. “Here I came back with skills.”

Mobley drove past his former neighbor’s house every day on his way to work, but eventually he told himself to let it go and not do anything rash.

Mobley said it was this self-restraint that he admired most in Martin Luther King.

“You have to think this way through,” Mobley said. “You can’t react because of what somebody did because sometimes the consequences will come out more on you.”

Mobley was critical of the riots that occurred after King’s assassination. “Blacks were burning their own neighborhoods up, and that didn’t make no sense because they were only hurting themselves.”

“Martin Luther King was the person that was holding everything together.”

In 2014, Mobley returned to his old home in Mobile and was shocked to find a place he no longer recognized.

Mobley ate at a restaurant where he wouldn’t have been able to sit down when he was growing up and was served by a white waiter. People were treating him normally, he said. “Nobody was even giving me the first thought.”

He was pleasantly surprised.

“The world had changed on me.”