For nearly 100 years, Temple Beth-El has been a landmark for the Reform Jewish community in Great Neck.

As the first synagogue on the peninsula, Temple Beth-El was breaking new ground for Jews on Long Island.

“This wasn’t even the suburbs,” Temple Executive Director Stuart Botwinick said. “This was the sticks.”

“It wasn’t even clear whether there would be enough people here to have a Jewish community when they started in 1928,” he said.

Soon enough, however, it would turn out to be a good investment, and the community would grow to serving 1,500 families with 500 families on its waiting list, Botwinick said.

Today, the past looms large as the congregation has fallen to around 400 congregants and the administration plans on selling its building.

Throughout the years, the synagogue has had many notable names in its congregation—comedian Andy Kaufman, Mets owner Steve Cohen, and businessman Sidney Jacobson.

The temple has also spawned several offshoots.

In 1940, Temple Israel branched off from Temple Beth-El to serve as a conservative synagogue and in 1953 Temple Emmanuel broke away to serve the growing Reform community that could not be served by just one temple.

Temple Beth-El has also been at the forefront of many progressive social movements, including Black, women’s, and LGBTQ rights.

“My faith is very much bound up with pluralism,” Senior Rabbi Brian Stoller said. “We have something to learn from everybody.”

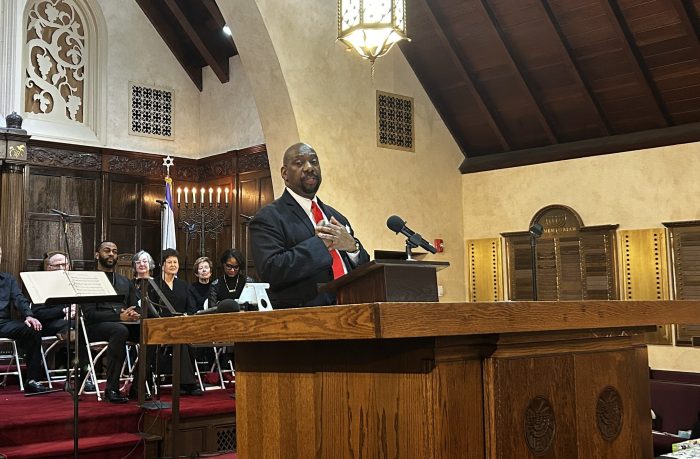

In 1967, during the throes of the Civil Rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Temple Beth-El’s bema.

And in 1976, the synagogue ordained the first female cantor in Jewish history, Barbara Ostfeld.

“Jewish tradition teaches that God gave the Torah on Mount Sinai, and that everybody received it a little bit differently,” Stoller said.

“God is infinite. We’re finite beings, so we can’t perceive the totality of God. We can perceive just a little piece, and everybody has a little piece of that puzzle.”

Botwinick said Temple Beth-El has a universalist approach to Judaism and a focus on serving others.

“This is how we live our Jewish values,” Botwinick said. “We don’t just pray about doing good. We don’t just talk about it, but we actually get our hands dirty.”

Temple Beth-El offers many programs for volunteering and social action.

One of its banner programs is the Great Neck Interfaith Food Pantry at St. Aloysius Church that serves families in need on the peninsula.

The temple provides food for students at Great Neck Public Schools during summer sessions when they do not have breakfast programs

Temple Beth-El also holds several adult Jewish learning classes to support Jewish education for its aging congregation.

“It’s through learning that I gain a wider view of the world,” Stoller said. “The most powerful way in which I connect spiritually is through deep study and encounter with ideas.”

But in recent years, the Reform community’s numbers have been falling in Great Neck, and there has been a demographic shift as more Orthodox Jews have moved into the area.

Botwinick said younger Reform families are no longer moving to the peninsula, and the congregants that are still there are getting older.

When Stoller joined the congregation as senior rabbi three years ago, he said he knew that Temple Beth-El was facing demographic headwinds.

He said he knew it would be a challenge, but that was what excited him about the position.

Under Stoller’s leadership, the temple announced a plan to downsize. Temple Beth-El plans to sell the building and lease a smaller portion for the congregation.

Currently, the temple rents out some of its space to an Orthodox yeshiva after it closed its own Early Childhood Education Center.

“That’s reflective of how Great Neck has changed,” Stoller said over the cheers and yelps of children in the background.

“Historically, it was about how big can you build your building? How nice can you make your building?” Botwinick said, but now “a building that was built for 1,500 families is no longer of need to us.”

“Members feel a certain sense of loss,” Stoller said. “There’s a lot of nostalgia for how things used to be.”

Botwinick said the decision was not just about financials but about priorities too. He said the synagogue would shift its focus towards the services it offers.

“It’s not the best use of our time to be managing a building for other people,” he said. “It’s no longer about just a building. This is really about the programs and the services.”

Temple Beth-El briefly considered merging with Temple Tikvah of New Hyde Park but decided to remain separate congregations.

Stoller said the congregation remains committed to social justice, in keeping with its long history of solidarity with various liberation movements.

Stoller recently gave a sermon on the rabbinic voice during different circumstances.

When a community is going through grief or experiencing fear, Stoller said a rabbi must assume a pastoral voice, one of comfort and reassurance. Other times a rabbi must push for pluralism.

“This particular moment, in my view, demands a prophetic voice,” Stoller said, “A voice of moral clarity.”

Stoller said the cruelty and violence of ICE amounted to “a moral emergency.”

“What’s happening in this country is wrong,” he said, and invoked MLK in saying“Silence is complicity.”

Stoller also invoked his own Jewish tradition as reason for his views on the Trump administration.

“Our Torah says, 36 times, be kind to the stranger because you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

The temple’s progressive stances on social issues aren’t the only things that have stayed the same over the years of change.

Many community members have stuck with Temple Beth-El and continued to bring their children and grandchildren.

Botwinick said just recently that the temple hosted the bar mitzvah of a 4th-generation Temple Beth-El congregant.

“If you talk to people who are Jewish from the North Shore of Long Island,” Botwinick said, “inevitably, there’s some connection here. They had a Bar Mitzvah here. They were married here. They know the rabbi. There was something that went on in their life that connects them back to Temple Beth El.”