SHOCK TREATMENT

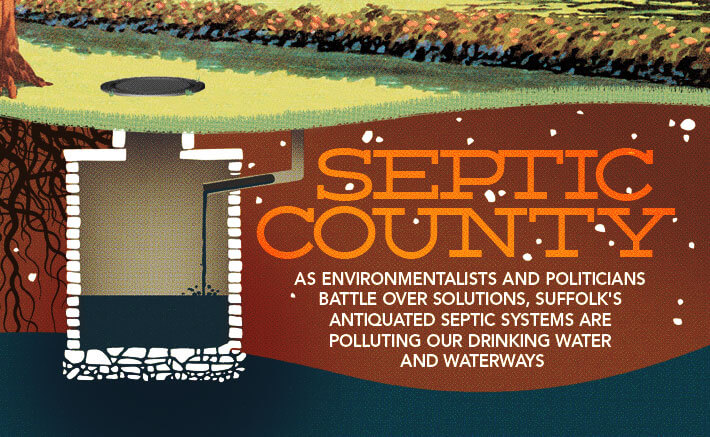

Suffolk’s wastewater dilemma has been flooding the consciousness of the county’s environmentalists, residents and elected officials in recent months.

On the table is a proposal from Legis. Sarah Anker (D-Mount Sinai) to speed up the county health department’s permit process for approving sewer and septic systems in new developments and help businesses track their applications during the process. New Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone said in his campaign that the delays in the health department’s permit process are unconscionably slow, hindering the county’s economic growth and recovery.

Earlier this month, the Suffolk County Legislature created a committee to study expanding sewers in the county. Lawmakers also recently created an “infrastructure bank” designed to foster private-public partnerships to help fund such sewers. At some point this fall, county officials hope to hold a public referendum on either expanding Babylon’s Southwest Sewer District—currently the only area of the county fully sewered—or creating an entire new sewer district; sewers are seen by many as key for future development in Suffolk.

“The present grade of cesspools is one step better than an outhouse,” says Legis. Wayne Horsley (D-Babylon), who led the sewer committee’s formation. “If you want to have businesses that will bring in good paying jobs, you have to have the infrastructure to advance the county. And that basic infrastructure is sewering.”

Kick-starting much of the recent discussion has been the aforementioned draft Suffolk County Comprehensive Water Resources Management Plan, released last January—the final, revised version of which is due out by June, according to the health department—that paints a disturbing picture of the health and protection of LI’s drinking water supply and waterways.

Levels of Tetrachloroethene (PCE) in the drinking water supply, for example—recognized by the EPA as a carcinogen—have been increasing exponentially, “detected in four times as many wells in 2005 as in 1987,” it reads.

Trichloroethene (TCE), a degradation product of PCE, “was detected in more wells—and at higher average concentrations—in 2005 than in 1987.”

MTBE, or Methyl tert-butyl ether, a flammable, volatile, colorless gasoline additive, has been detected in Suffolk’s groundwater since 1991.

High-density development that occurred after World War II and eastern Suffolk’s long history of farming are two main culprits of nitrogen contamination, according to the report. Since many contaminants take years to travel from groundwater to surface waters, much of the destruction witnessed today began back then, though antiquated cesspool systems continue to contribute to that murky tradition.

“The biggest threats to drinking water are nitrogen, volatile organic compounds and pesticides,” Bellone tells the Press. “We agree that more work needs to be done to protect our aquifer, particularly with respect to nitrogen and surface waters.”

The draft plan “has got to be a wake-up call that the job is not being done to protect our drinking water and manage our waste water,” says Michael White, an environmental law attorney and the former executive director of the Long Island Regional Planning Council.

But as comprehensive as the latest report is, it still falls short, argue environmentalists.

“The data gets us to the 10-yard line, but it never kind of puts the ball into the end zone,” says Robert DeLuca, president of Southold-based nonprofit Group for the East End and also a former employee of Suffolk’s health department. “It essentially said, ‘Wow, look at all the stuff that’s happening, and we’ll keep doing the best we can.’”

DeLuca, McAllister, and half a dozen others co-published their gripes in an 18-page critical response to the report last August, titled Water Worries: Suffolk Report Documents Decline Without Prescription for Remedy. Their concerns were also submitted to the county health department during its public comment period, to be factored into potential remedial plans for its final report due in June.

Christopher Gobler, PhD, director of the Stony Brook-Southampton Coastal and Estuarine Research Program, also weighed in. He has worked extensively with the algal blooms infecting Northport Harbor, commonly known as red tide, which produces toxins that can be poisonous to humans.

“The levels of nitrogen have gone up and will continue to go up,” Gobler tells the Press. “The amount of nitrogen in the groundwaters is a function of the number of people living above the ground. And without a sewage treatment plant for almost all of eastern Suffolk County, every time you add another home with a septic tank and have people living in that home, you’re going to drive up the nitrogen loads. It’s all very predictable.”

Besides the foul smells and effects on the aesthetics of the Island’s bays and rivers, Gobler stresses the impact on the local economy.

“In 1980, two of three hard clams eaten east of the Mississippi River came from Great South Bay,” he writes. “Landings of hard clams and bay scallops have diminished 99 percent since this time, in part due to N[itrogen]-stimulated harmful algal blooms.”

Then there’s the health threats ingesting too much nitrogen from our drinking water poses: It deprives the blood of oxygen, explains Gobler, and can cause “Blue Baby Syndrome” in infants, whereby the child’s skin literally turns blue.

Casting blame on any one agency or facility for accountability, however, is tough. When it comes to exactly who is responsible for protecting Long Island’s drinking water, it gets complicated.

“There’s multiple agencies at multiple levels that currently have some piece of this responsibility, and I think that’s the challenge,” says DeLuca. “The Suffolk County Health Department has a responsibility for the protection of drinking water and the sanitary waste disposal systems that are in the ground right now. The state Department of Environmental Conservation is responsible for the protection of surface waters and wetlands. They have their own sets of rules and regulations. The local towns and villages, many of them have their own ordinances, planning and zoning. So you have probably a half dozen agencies all with a foot in the pool here.”

Richard Amper, executive director of Riverhead-based nonprofit Long Island Pine Barrens Society, an oft-outspoken environmental advocate, put it more bluntly:

“If there were a single somebody in charge of groundwater quality on Long Island, you’d go to them and take them out behind the barn and shoot them in the head,” he blasts. “Surface water is the DEC. They will tell you they’re understaffed. If it’s drinking water, it’s Suffolk County Department of Health Services. And they’re understaffed and they’re not processing development applications as fast as the government wants them to.

“Whatever level of government that you’re talking about, everyone’s falling down on the job—collectively, and all at the same time—and the consequences are catastrophic,” he adds.

Amper is part of a growing number of local environmentalists calling for the creation of a singular agency or commission that would oversee all of the Island’s drinking water resources. Adrienne Esposito, executive director of Farmingdale-based nonprofit Citizens Campaign for the Environment, is another. And she stresses that whatever form this new body is, it’s got to have teeth.

“We don’t want a paper tiger,” she says. “We want an entity that has the force of law.”

One role for this theoretical commission, she says, would be monitoring and enforcing the wastewater discharge standards of sewage treatment plants and onsite wastewater treatment systems and their pollutant infusions into the drinking water supply.

Currently 10 milligrams per liter of wastewater discharge for nitrogen is a standard that McAllister wants changed to 5 milligrams, since, he argues, the threshold was created to address health concerns with drinking water, not surface water quality. Long Island’s water bodies begin to deteriorate due to nitrogen pollution at 0.5 milligrams per liter, he says, thus the higher the requirements for nitrogen discharges, the better the health of the bays and estuaries.