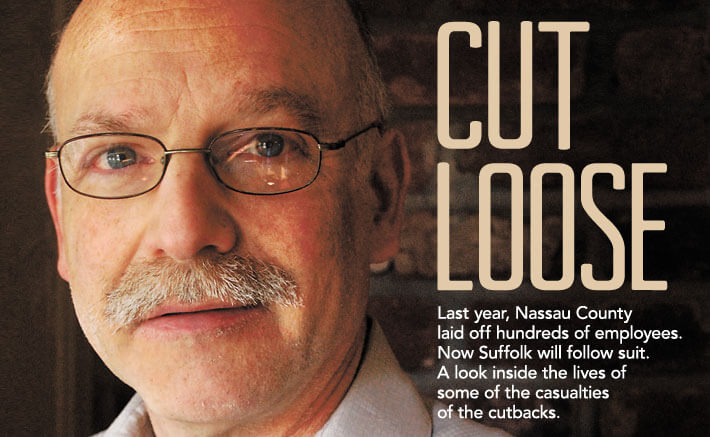

The aroma of sauerbraten filled Angela Vignali’s cozy one-bedroom apartment in Westbury. It was Valentine’s Day, and she was cooking dinner for her boyfriend, Henry, who is of German descent. The next morning she will go to the gym in her new Toyota. In the afternoon, she will take her three young grandchildren—Nicholas, Christian and Daniel—to get ice cream.

At 65, Vignali is living the retired life she had long dreamed of. That dream, however, was not supposed to start for another year.

Feb. 24, 2013 was marked on Vignali’s calendar as the day she would retire with her 20-year pension. After nearly 19 years of working as a messenger, tasked with interoffice mail collection and delivery in the Nassau County Department of Social Services, Vignali’s annual salary was about $40,000. For Nassau civil servants, 20 years of service is a magic number. At 20 years, a county employee can retire with a pension equaling roughly 40 percent of his or her final annual salary.

Instead, Vignali was laid-off on Dec. 29, 2011, along with more than 260 other Nassau employees, in an attempt by County Executive Ed Mangano to close a $310 million budget gap without raising property taxes, which are already among the highest in the nation. Yet public sector job slashes aren’t only relegated to Nassau. Nationally, state and local governments have shed 611,000 employees—196,000 of them educators—since the beginning of President Obama’s term, according to a recent article in The Washington Post. Earlier this week, in an attempt to bridge a $530 million multi-year deficit, Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone informed 315 of its county workers that they’d be let go at the end of June. They’ll join the 88 who have already been laid off throughout the past several months.

Martin Melkonian, an economics professor at Hofstra University, tells the Press cuts to the public workforce during tough financial times are nothing new and that the latest bloodletting may not be through.

“It’s fairly typical of many local governments that are in trouble budget-wise,” he says. “One of their resorts, instead of raising taxes, is to lay people off. That’s the direction that we’re headed.”

Yet while the job cuts may enable the county executives to achieve their financial targets on paper, whether the measures will help either county’s economic situation, is debatable.

Frank Mauro, executive director of the nonprofit Fiscal Policy Institute, says such deep cuts in the public municipal sector may actually be doing more harm than good on Long Island’s local economy, further exacerbating already tough fiscal times for the middle-class.

“That kind of action creates a downward spiral in economic activity,” he explains. “People have less income, they consume less… Austerity doesn’t stimulate the economy. It takes demand out of the economy.”