Mary Laura Lamont, a park ranger at Fire Island National Seashore, shortened her bucket list as she recited a ditty to a full house at the end of her talk on the William Floyd Estate at the Koenig Center on Feb. 22. Several years ago she had been doing research on the Lloyd family and in a file at the Huntington Library she found this ditty.

“I always wanted to recite it in Oyster Bay,” she said.

“Where are the stones that mark the bones

Of those who die in Oyster Bay?

“There are no stones to mark the bones

Of those who die in Oyster Bay,”

“On clams and such nutritious foods,

They lived to Resurrection Day!”

That Sunday, a respite from the recent cold weather onslaught, the Power Point presentation was complimented by the exhibit at the Oyster Bay Historical Society. Photographs taken by Xiomáro of the William Floyd Estate, a National Park unit of Fire Island National Seashore, were displayed on the walls. The Other Side: A photographic memorial to the slaves at the William Floyd Estate, is also a documentation of the life of the family that lived there for 250 years.

William Floyd (1734-1821), a plantation and slave owner with roots in Wales, represented New York in the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He signed the Declaration of Independence in July 1776. Three hundred years later his descendants, Cornelia Floyd-Nichols and her children, donated the fully furnished Old Mastic House to the NPS. It is a cultural preservation, a glimpse into 250 years of decorative history of the country showing how tastes changed and new items were integrated into the house as rooms were re-purposed over the years.

Lamont talked about the estate of William Floyd, the youngest of New York State’s four signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Grace Searby asked Lamont about the house, saying that many of the homes of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were burned down. Lamont explained that in view of the British occupation of Long Island, Floyd had sent his wife and children to Connecticut and he was busy in Philadelphia with the Continental Congress and served there until the end of the war. But the British had occupied the house during the war and when he returned in 1783, he came back to a decimated plantation. Even the woods had been cut down and the lumber sent off for sale, said Lamont.

The Xiomáro exhibit includes photos of the slave graves that Lamont called a memorial to the workers mentioned in histories of the house. Cornelia Nichols’ grandchildren, who grew up in the house, have permission to be buried in the cemetery on the property.

Lamont, a naturalist, a former compiler of the Orient Christmas Bird Count who worked during the 1970s at Oyster Bay’s Theodore Roosevelt Sanctuary and Audubon Center, said that morning she had been watching eagles. She said the birds had not been seen since the 1930s on the Floyd Estate. Currently, she has been watching a male bald eagle and a 3-year-old female nesting in an Osprey nest on the site. Lamont explained the American Bald Eagle was on the endangered list and has been coming back. There are currently three nests known to be on Long Island. He was adding sticks to the nest to make it larger. Eagles nests are known to be very large. After adding some sticks to the nest the couple soared into a courting flight.

Lamont had interesting family stories to tell. She showed a slide of a miniature of Catherine “Kitty” Floyd who was engaged to James Madison, but decided instead to marry a Philadelphia doctor, for which her father never forgave her because of his lasting friendship with (President) Madison. The chosen doctor left his profession and became a pastor in the south, which meant Kitty lived in poverty. Floyd had cut her out of his will, but his remaining children got him to give her a small inheritance, Lamont said.

Floyd did well over his lifetime, including being honored for his Revolutionary service by being given 10,000 acres of land along the Mohawk River. Lamont reminded the audience that the Mohawks had fought on the side of the British.

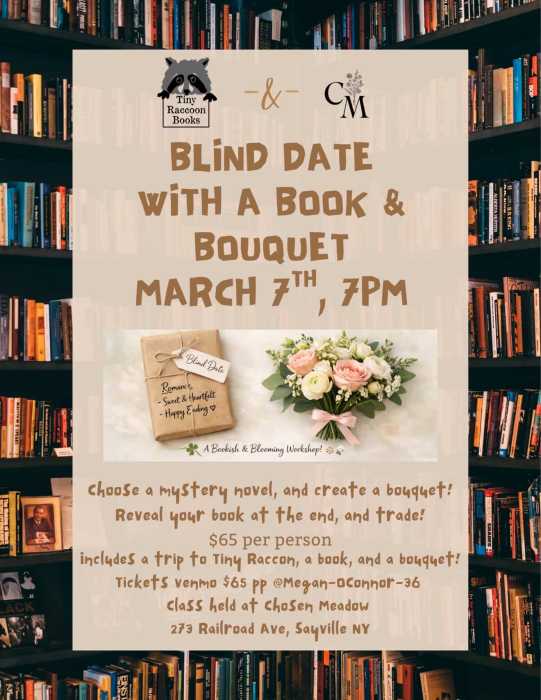

Jacqueline Blocklyn had baked a rich chocolate cake for the reception, which guests enjoyed. Philip Blocklyn, OBHS executive director, mentioned the next events at the center including a Sunday, March 8 at 2 p.m. lecture on the History of the Doxsee Sea Clam Company by Bob Doxsee.

On Wednesday, March 11 at 2 p.m., photographer Xiomáro will be lecturing on his involvement with photographing other sites for the National Park Service. On Wednesday, March 25, a fundraiser Ye Olde Fatted Lambe Tavern takes place at the OBHS from 6 to 9 p.m., for a fee of $125, per person. It is a fundraiser based on the Andros Patent

The OBHS is at 20 Summit St. in Oyster Bay. Attendance is free and open to all. Contact the Oyster Bay Historical Society at 516-922- 5032 for more information or visit them at www.oysterbayhistorical.org.