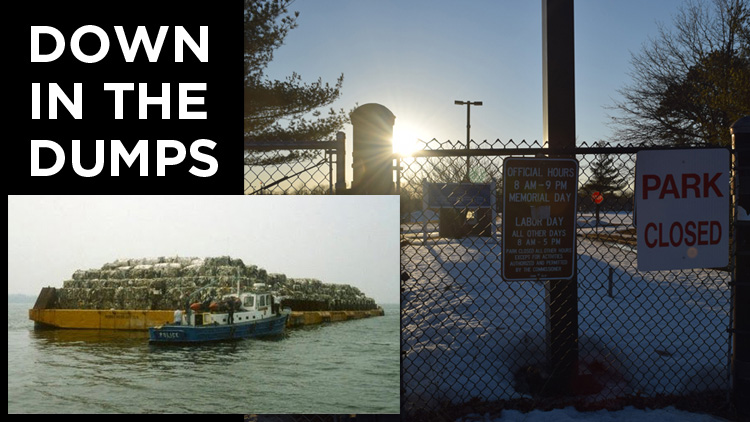

One year after Islip marked the 25th anniversary of the infamous garbage barge that made it a national laughingstock—and all the environmental progress it’s made since—politically connected haulers allegedly dumped toxins in town parks.

But calling the Town of Islip home is not all the two environmental crises share in common. Both also gained notoriety beyond Long Island’s shores, sparked inquiries of how the region disposes of its waste and will linger for years to come. Of course, there are as many differences as there are parallels between the cases—most notably, only last year’s incident resulted in arrests.

“The town is a study in contrast,” said Adrienne Esposito, executive director of the Farmingdale-based nonprofit Citizens Campaign for the Environment, which gave the town an “A” on its recycling report card in 2008—the only one of the 13 towns on LI to earn such a high grade in the first year the audit was conducted.

“They were very effective in implementing and pursing a successful recycling program…and that’s a great thing,” Esposito said. “But, on the flip side, we have the illegal toxic dumping scandal in the parks. It’s clearly two steps forward, four steps backward.”

The recycling program is among efforts Islip officials launched to rehabilitate its image after six states and three foreign nations turned away the barge full of its garbage when allegations surfaced that it was tainted with hospital waste. That barge, the Mobro 4000, had set sail on March 22, 1987—28 years ago Sunday. When nobody would take it after six months at sea, the trash was incinerated in New York City and its ashes were buried in the town’s Blydenburgh Landfill.

“The situation was a wake-up call about the sorry state of waste disposal in this country and lack of effective recycling programs,” wrote Nancy Cochran, executive director of Keep Islip Clean—a nonprofit anti-litter group that the town founded two years after the barge incident—for an article published last year in Great South Bay Magazine. “It’s a great example of taking lemons and making lemonade,” observed Cochran, who declined to comment for this story.

Giving that lemonade a twist of alleged public corruption is ex-Islip Parks Commissioner Joseph Montouri Jr., who is accused of allowing companies linked to Thomas Datre Sr. and his son, Thomas Datre Jr., to dump up to 1,800 truckloads—about 50,000 tons—of toxin-laced debris at Roberto Clemente Park in Brentwood. The haulers are also accused of dumping similar debris at a Police Athletic League ballpark in Central Islip, a veterans housing complex in Islandia, and in wetlands in Deer Park. Properly disposing of that amount of acutely hazardous material is estimated to cost about $3 million at an out-of-state facility.

“They did it pure and simply for money,” said Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota in December upon announcing the arrests of Montouri, the Datres and three subordinates, who were charged with criminal violations of environmental and public health laws. The same motive was true for the garbage barge’s backers, who were trying to capitalize on regulations enacted at the time that had closed many small LI landfills, leaving only large regional dumps that forced trash carters to seek alternatives.

In the illegal Islip dumping case, all have pleaded not guilty. The attorney for the Datres and their businesses has said the case is a manufactured scandal designed to cut off the family’s donations to the local Republican Party, which has the majority on the Islip town board. Either way, the fallout has only just begun.

LITTLE LIES

Marking a quarter century since the historic voyage of more than 3,000 tons of trash that nobody wanted was “Garbage Barge Revisited: Art from Dross,” an Islip Art Museum exhibit of sculptures and other works made from recycled material, held in the summer of 2012. The following year is when authorities now believe the toxic dumping began, although arrests weren’t made until December 2014, following a lengthy investigation.

While both cases seem to have unearthed their share of public hysteria, only the barge became fodder for The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and mock concert t-shirts, such as one that read: “Islip Garbage World Tour ‘87.”

“That had humor,” said Russ Moran, an assistant town attorney at the time, while recalling “the good ship Mobro.” But the current dumping scandal—and the carcinogens authorities say they’ve found in the soil—is deadly serious. “There’s nothing funny about this,” he said.

Funny or not, both also became campaign issues. Phil Nolan, a Democrat who unsuccessfully tried in 1987 to unseat then-Islip Town Supervisor Frank Jones, recalled making an issue of the barge debacle on the campaign trail. Jones kept his job until ’93. Nolan later won on his fourth try, in 2006.

“The biggest parallel of all, I think, is the one-party control,” recalled Nolan, who is now president of the Suffolk County OTB. “In both instances there were 5-0 Republican town boards… It’s the Islip Republican Party that gave you both of them.”

Frank Tantone, chairman of the Islip Town Republican Committee, declined to respond to Nolan’s remarks.

One of the current town councilmen, Anthony Senft, is actually a Conservative Party member. As liaison to the Islip parks department when the scandal broke, he took much of the heat while simultaneously running for New York State Senate against Esposito, the environmentalist, who dubbed him “Toxic Tony.” After Senft dropped out, Republican Islip Town Supervisor Tom Croci, a Navy reservist who had unseated Nolan in ’11, entered the race and won the state Senate seat. He wasn’t tarnished by the dumping scandal because he had been deployed overseas when the news broke.

That left Croci’s successor in town hall, fellow Republican Angie Carpenter, who had previously been Suffolk County treasurer, to clean up the mess that prosecutors allege Croci’s appointee, former town parks commissioner Montouri, helped make. Carpenter did not mention the scandal when she was sworn in earlier this month, but the town has a deadline of this Thursday on a request for proposals for contractors to bid on the cleanup job. Town officials have forecast that remediation and rebuilding the park will cost about $6 million, but suspicions abound that costs will rise.

Croci said last year that he’ll help fix the disaster from Albany, but he did not return a request for comment on what exactly he has done on this issue in the first three months that he has represented the 3rd Senate District.

“He has been very, very open about wanting to help in any way possible,” said Carpenter, noting that she hasn’t had an opportunity to talk specifics with Croci yet. The new supervisor—who recalls defending former Supervisor Jones in an episode of The Phil Donohue Show before she began her career in elected office—believes the town will clean up the mess sooner rather than later.

“It’s not going to linger for years,” Carpenter said. “It’s something….we’re going to move on…as quickly, safely and responsibly as we possibly can.”

DEF CON ONE

With remediation underway at the Islandia veterans housing complex and Central Islip ball field, some of the cleanup has begun, but regardless of when the Brentwood park and Deer Park wetlands are restored, the case is sure to drag on in court.

Aside from the complex criminal case—which has sparked a separate grand jury investigation—several lawsuits are in the works related to the toxic dumping. Residents have said that they plan to sue the town, the town has said that it plans to sue the alleged dumpers and even the New York State Attorney General’s office might get in on the action.

“Our office is also exploring the possibility of civil enforcement action to seek redress for the community surrounding Roberto Clemente Park,” said Elizabeth DeBold, a spokeswoman for Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, in a statement.

In the case of the Mobro 4000 garbage barge, the litigation over how to dispose of its trash lasted only months. Complex lawsuits such as those in Islip’s dumping scandal will likely last years before being resolved.

When exactly Roberto Clemente Park will be able to reopen, nobody knows.

WHERE THE STREETS HAVE NO NAME

If it wasn’t bad enough that North Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and New Jersey refused to take the Mobro’s rotting cargo, it became an international incident when Mexico, Belize and the Bahamas followed suit.

Multinational elements emerged in the dumping scandal as well. That’s because the Islandia veterans housing complex was built for veterans returning from combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. And the two parks dumped upon are in the communities of Brentwood and Central Islip, which are both among the few LI hamlets where Hispanic residents make up the majority of the population.

“Community members in Brentwood and Central Islip saw this as another instance of environmental racism,” said Daniel Altschuler, Civic Engagement and Research Coordinator for Make the Road New York. There have also been language barriers between residents and the town that left some in the community feeling as though their concerns were not heard.

The public outrage has led to multiple rallies at town hall, where advocates for the communities have blasted the town board for their response to the dumping at nearly every meeting since news of the scandal broke. Similarly, environmental activists with Green Peace hung a giant banner on the Mobro barge that read: “Next time try recycling.”

The question now is: Will the Islip town toxic dumping scandal serve as the same wake-up call that its garbage barge did three decades ago, or will the town try to sweep it under the rug after the park eventually reopens?

—With additional reporting by Jaime Zahl