An earlier article highlighted the issue of infant mortality in the Jones family. Thomas Jones and his three sons sired 45 childr en, 15 of whom died in infancy before age three. His grandsons suffered much the same loss, a puzzling situation in view of their status as wealthy landowners, lawyers, businessmen, namely, people who presumably had access to superior health care. Their experience with infant mortality reflected that of the larger society in the 1800s, according to several studies from the Centers for Disease Control.

en, 15 of whom died in infancy before age three. His grandsons suffered much the same loss, a puzzling situation in view of their status as wealthy landowners, lawyers, businessmen, namely, people who presumably had access to superior health care. Their experience with infant mortality reflected that of the larger society in the 1800s, according to several studies from the Centers for Disease Control.

After the American Revolution, the Jones family split into two branches: the Joneses, many of whom were Tories, sympathetic to the British Crown, and those that became known as the Floyd-Joneses, who had supported the Revolution. The Floyd name comes from the family that lived in an estate in Mastic that stands today and that gave us William Floyd, who signed the Declaration of Independence. The hyphenated Floyd-Jones name was recognized by the New York State Legis lature in 1788. Family members controlled most of the Massapequas, while most of the Jones clan moved north to the Cold Spring Harbor area. The Floyd-Jones family experienced the pain of infant mortality, as had their Jones forebears, but at a steadily decreasing rate throughout the 19th century.

lature in 1788. Family members controlled most of the Massapequas, while most of the Jones clan moved north to the Cold Spring Harbor area. The Floyd-Jones family experienced the pain of infant mortality, as had their Jones forebears, but at a steadily decreasing rate throughout the 19th century.

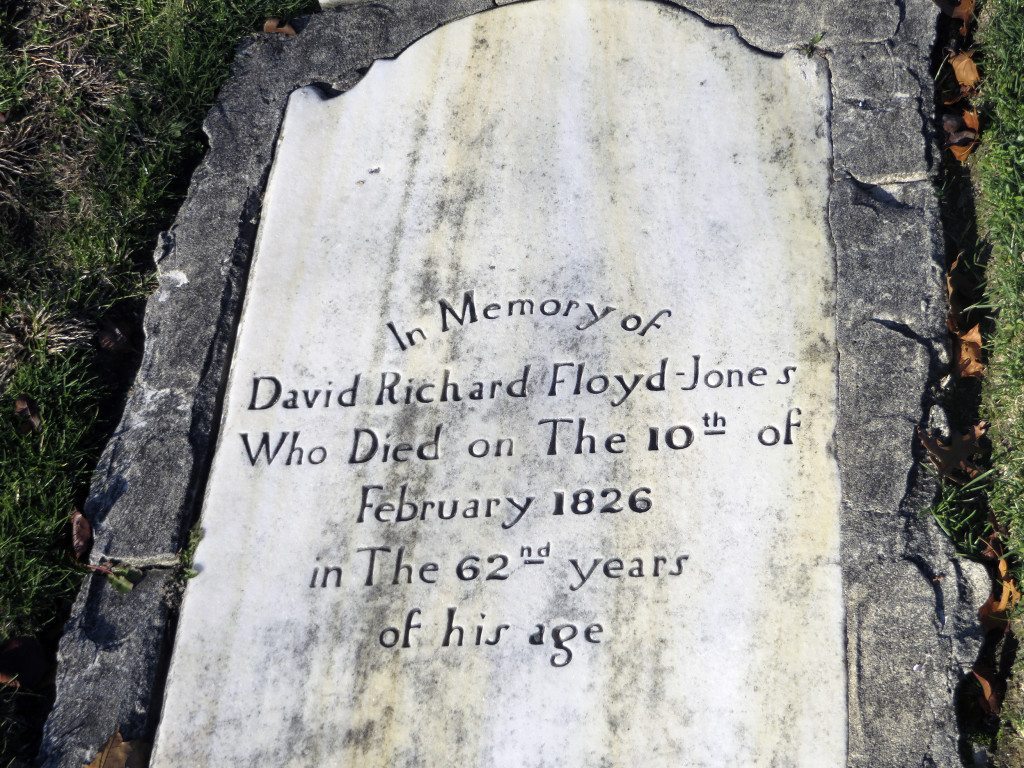

David Richard Floyd-Jones was the first to have his hyphenated name recognized in law. He was born in 1764 and moved to the Massapequas in 1783 at the end of the Revolution. He had five children, three of whom (David in 1787, Arrabella in 1790 and Andrew in 1794) died in infancy. It appeared the 18th century pattern of infant mortality would continue, but there is a remarkable absence of infant deaths among the Floyd-Jones descendants for the next half century. Neither The Jones Family Genealogy of Long Island by John H. Jones nor the current genealogical charts of the Jones and Floyd-Jones families (corrected to 2007 and available for review in the Floyd-Jones Library) records a single death in infancy. The next recorded death after 1794 is that of Stanton, son of David Richard II, who died in 1848. He was followed by his brother Thomas in 1861. They were two of David Richard II’s seven children. David Richard II was, however, the grandson of David Richard I, so the generation between the two men avoided the trauma of infant mortality.

Elbert Floyd-Jones, who was David Richard II’s brother, had 11 children. Two died in infancy, Mary in 1855 and Sarah in 1870. Of his children, his son George lost two of his three children in infancy (George Jr. in 1866 and Emily in 1870). Another son, Edward, lost one of his two children in infancy (Constance in 1900), and his daughter Emily lost two of her six children as infants (Robert in 1875 and Gertrude in 1882).

So infant mortality remained an issue within the Floyd-Jones family, but there was a notable, and unexplainable, absence of deaths in the first half of the 19th century, and the frequency diminished in the latter half of the century. Family members lived in New York City during the cold weather and in the Massapequas in the warmer months. The older parts of the city, below Houston Street, became more crowded and unsanitary, but the area around Washington Square, where many of the Floyd-Joneses lived, was considered healthier because it was filled with private houses. By the second half of the century, New York had established a system of reservoirs and aqueducts bringing fresh water to residents and eliminating epidemics such as cholera. Indoor heating and plumbing became available to the wealthy during that period. At the same time, Floyd-Jones family members came to spend a larger portion of each year in the Massapequas, accessible by train after the Southside Railway was completed in 1867 and home to a ready source of food from the farm district in the northwest.

the Massapequas in the warmer months. The older parts of the city, below Houston Street, became more crowded and unsanitary, but the area around Washington Square, where many of the Floyd-Joneses lived, was considered healthier because it was filled with private houses. By the second half of the century, New York had established a system of reservoirs and aqueducts bringing fresh water to residents and eliminating epidemics such as cholera. Indoor heating and plumbing became available to the wealthy during that period. At the same time, Floyd-Jones family members came to spend a larger portion of each year in the Massapequas, accessible by train after the Southside Railway was completed in 1867 and home to a ready source of food from the farm district in the northwest.

The many mansions built along Merrick Road provided comfort and convenience, and the Floyd-Joneses had access to medical care that had advanced enormously because of the experience of caring for sick and wounded soldiers during the Civil War. The Massapequas also became known as the place where wealthy New Yorkers could find relief from overcrowding in New York City, as evidenced by the 15 hotels built in the area during the 19th century.

In summary, the Floyd-Jones family shared in the overall improvements in medical care and living conditions that caused infant mortality to decline through the 19th century in the United States.

George Kirchmann is a trustee of the Historical Society of the Massapequas. His email address is gvkirch@optonline.net.