“Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.”

So observed W.H. Auden of William Butler Yeats, Ireland’s leading poet of the 20th century.

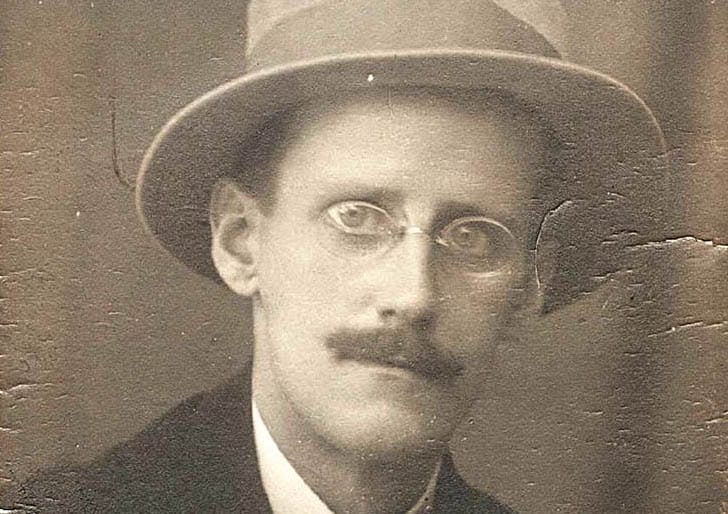

It hurt James Joyce, Yeats’ countryman, into poetry too, prose poetry in this case. The emerald isle also hurt the man into exile. Joyce, the eldest of a Dublin family of 10 surviving children, left his homeland at age 22 and never looked back. A graduate of University College of Dublin, Joyce was a top student, becoming proficient in French and Italian. A product of a poor family that literally roamed from rented house to rented house, Joyce had all the incentives in the world to climb his way into the middle class. He thought about becoming a physician. Alas, the writing bug had hit. At age 19, Joyce discovered the dramatic works of Hendrik Ibsen, the famed Norwegian playwright. He considered Ibsen to be the greatest of all dramatists, Shakespeare included. Joyce, to his father’s chagrin, would embark on the luckless life of the writer.

Luckily, Joyce had found the right companion for the journey. In 1910, Joyce met Nora Barnacle, a chambermaid two years Joyce’s junior. Nora didn’t understand Joyce’s literary ambitions, but she was convinced of his genius. The couple eloped to Italy, where Joyce, already multi-lingual, would find steady work as an English teacher.

Joyce had to leave Ireland to write about it and in his early 20s, the young man was already 900 pages into his “Stephen Hero” novel, later re-written and published as Portrait Of An Artist As A Young Man. He also completed his classic short story, “The Dead.” In 1907, Joyce published his first book of poems, Chamber Music. Next came the short story collection, Dubliners. Then followed his debut novel, the above-mentioned Portrait. Joyce had now announced to the world that his subject would be Dubliners, a people too poor and too proud to live under any foreign domination.

Joyce’s mother, May, a woman who became pregnant with no less than 16 children, died when the novelist was only 20. This probably explains his attachment to Nora. In addition to Nora, he had found literary and financial angels. Sylvia Beach, proprietor of the legendary Paris bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, published Joyce’s magnum opus, Ulysses, in 1922. Harriet Weaver, a supremely attuned patron of the arts, became the man’s benefactor. Joyce and his family, which now included a son, Giorgio and a daughter, Lucia, were free to live in relative style in Paris. It took Joyce seven years and “20,000 hours of work” to write Ulysses, a process that severely damaged his eyesight, but history was made. Ulysses was published the same year as T.S. Eliot’s book length poem, “The Wasteland.” After decades of stagnation, the English language was given a needed jet-propelled boost.

Publication of Ulysses was just the beginning of the novel’s story. Explicit language caused it to be banned in the United States until a 1934 court ruling allowed its stateside publication. In 1923, Joyce embarked on a new novel, Finnegan’s Wake. This 656-page opus took another 16 years to write and was finally published in 1939, two years before the man’s death in 1941.

Time has been good to James Joyce. In 1998, Modern Library published its highly-publicized top 100 novels of the century. Ulysses grabbed the top spot beating out F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, while Portrait Of An Artist As A Young Man came in third. Two novels in the top five. John Joyce, the old man, would have been proud. The list was controversial, but no less so than the man’s literary output. Joyce’s early poetry and fiction were conventional in style, while his latter two novels were experimental. Ulysses was a “day” novel, telling the adventures of Stephen Dedalus, hero of Portrait and Leopold Bloom, the luckless newspaper advertising salesman as their fates intertwined on June 16, 1904.

Finnegan’s Wake was a sequence of nighttime stories about the Finnegans, another working-class Dublin family. Joyce himself defended this most difficult of all novels as an attempt to “reconstruct the nocturnal life,” “the dream of old Finn, lying in death beside the river Liffey and watching the history of Ireland and the world…flow through his mind like flotsam on the river of life.”

Joyce’s purpose was to capture the whole of life’s experiences. His work could not take place anywhere except in Dublin, a place that was more than home. Dublin was the world and, as he maintained, the life stories of its characters would tell the history of the human experience itself.

Ulysses worked because Bloom, a cuckold and an Irish forerunner to Willy Loman, was a sympathetic character. Dedalus as a surrogate son to Bloom, worked too. What Joyce intended was “an epic of two races (Israelite-Irish).” He had originally concluded the

novel with the two men’s nighttime carousing. Joyce then added on the Molly Bloom soliloquy—as rich, but rambling inner monologue of Bloom’s unfaithful wife.

The critical reception to Joyce’s corpus has been mostly positive, but it does have its critics. Defending her countryman, Edna O’Brien maintains that Joyce, in Ulysses, “was determined to break the taboos…that [were] repellent to Victorian England, puritanical America and sanctimonious Ireland.” Tom Landess, an American critic, denounced Joyce’s world view as frivolous. “The freedom of Stephen Dedalus and James Joyce…is freedom from social custom, freedom from family, freedom from tradition, freedom from church, freedom from the created order, freedom from God.”

The war over James Joyce will continue. His influence, meanwhile, has been enormous. There was a time when every other young aesthetic would carry a copy of Ulysses under their arm. Many would become writers themselves: Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges and Flann O’Brien. Joyce will continue to be read for the sheer vividness of his prose narrative. Dublin comes alive and indeed, Dublin becomes the world.