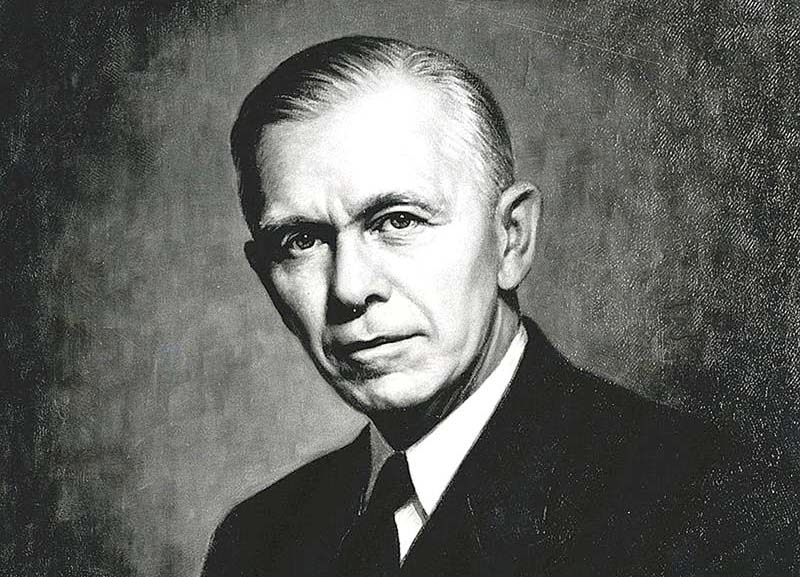

Who can forget the opening scenes of Saving Private Ryan? The viewer is taken into the office of Gen. George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff. All of the Ryan brothers, save one, have been killed in action. The Army must track down the surviving brother and deliver him to safety. Marshall was an unknown to the public, but the viewers immediately knew that they were in the company of a great and solemn man.

David L. Roll’s George Marshall: Defender of the Republic is being greeted with all the anticipation of a man at the end of his rope. “[The biography] couldn’t come at a more crucial time.” (John Lewis Gaddis). “A tonic for our troubled times.” (David Ignatius). “This is an important, even urgent, book.” (William I. Hitchcock.)

George Marshall’s life was the story of the 20th century. A native of Uniontown, PA, Marshall, whose family was related to John Marshall, the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, pined to enter the U.S. Military Academy in West Point. Turned down there, Marshall promptly applied for and was accepted to Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Today, the VMI sports a statue of Marshall alongside another famous general who once taught at that university, Thomas Jonathan (“Stonewall”) Jackson. Marshall was a man born to serve. Jackson’s fellow Virginian, Robert E. Lee, once declared that duty was his favorite word. “Duty is the most sublimest word in the language,” Lee once claimed. “Always do your duty. Never do less.” That, too, was Marshall. Winston Churchill called him the “organizer of victory.” This was true in both world wars. As Army Chief of Staff, Marshall was faced with a daunting task: Raising a 180,000-man army to match and defeat the armed services of both Germany (2.5 million men under arms) and Japan (1.7 million men in fighting condition). A year before Pearl Harbor, Marshall fought ardently for a peacetime draft. His stature on Capitol Hill helped to make victory possible. After the war, Marshall was set for retirement. That wasn’t possible. With victory in World War II, Marshall’s reputation had reached Olympian heights. Senators and Congressmen instinctively respected his judgment on all matters military and diplomatic. President Harry S. Truman wanted him to go to China to resolve a bloody civil war between nationalists loyal to Chiang Kai-shek and communist insurgents under Mao Tse-Tung. Again, Marshall answered the call. After China, no rest for the weary. He was now asked to serve as Secretary of State.

Marshall’s career was one of unparalleled service. He had his disagreements with his colleagues and superiors. Marshall would have preferred a 1943 Allied invasion of Europe rather than the June 6, 1944 D-Day. He agreed with U.S. recognition of Israel, but felt the Truman Administration was moving too fast (the president didn’t want the Soviet Union to be the first nation to recognize Israel), and he threw up his hands on the China mission. Marshall was frustrated with the nationalists, but the communists weren’t willing to give an inch, either. Marshall was nearly chosen as commander of Operation Overlord, the epic invasion of Europe through France. Both American and British administrators felt the man was more valuable running the Army from Washington, where he could report directly to the president. Dwight D. Eisenhower got the nod, and later, served two terms as president. A President Marshall instead? The man had no desire for electoral politics. Absent Ike, a Douglas MacArthur presidency was more likely.

Marshall’s career was one of unparalleled service. He had his disagreements with his colleagues and superiors. Marshall would have preferred a 1943 Allied invasion of Europe rather than the June 6, 1944 D-Day. He agreed with U.S. recognition of Israel, but felt the Truman Administration was moving too fast (the president didn’t want the Soviet Union to be the first nation to recognize Israel), and he threw up his hands on the China mission. Marshall was frustrated with the nationalists, but the communists weren’t willing to give an inch, either. Marshall was nearly chosen as commander of Operation Overlord, the epic invasion of Europe through France. Both American and British administrators felt the man was more valuable running the Army from Washington, where he could report directly to the president. Dwight D. Eisenhower got the nod, and later, served two terms as president. A President Marshall instead? The man had no desire for electoral politics. Absent Ike, a Douglas MacArthur presidency was more likely.

Marshall always kept his eye on Europe. He was a true Atlanticist. He reached the pinnacle of fame for the Marshall Plan, a program of economic aid to a devastated Europe. Marshall was willing to include both the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe nations in the plan. Moscow balked and they made sure Eastern European nations did the same. The Cold War was on. Was the plan necessary? In the winter of 1947, Great Britain nearly froze, saved by emergency American aid. Did Europe bounce back due to the deep pockets in Washington or the free market economy as articulated by Wilhelm Ropke, the famed Swiss economist who advised European governments? Marshall was as blunt as always. He acknowledged that such an aid package would cost the American taxpayer, a species who had just bankrolled the greatest war in history. Marshall made his own smart choices. Preeminent was the selection of George Kennan, a former ambassador to Russia, for a seat of the State Department’s policy planning board. Marshall had read Kennan’s legendary “Mr. X” essay on the sources of Soviet conduct. There, Keenan claimed that Russia acted out of a centuries-old fear of being isolated from the world rather than a Marxist-Leninist ideology. Kennan’s containment policy perfectly fit in with Marshall’s prudent style. Keenan was a prophetic statesman, but it was Marshall who placed him in a position of influence.

George Marshall is thorough, but plodding. The author compiles quote after quote, fact after fact. Marshall lived through dramatic times, but he was not a dramatic man. Marshall avoided the spotlight. When he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953, he apologized in advance for not being a Winston Churchill when it came to oratory. (The former had won the Nobel for Literature that year.) During the 1950s, the president of Harvard University declared Marshall to be the most accomplished American since George Washington. That was then. Marshall remains an unknown and this biography will make the reader regret the passing of a nation that could produce such men as Marshall, Eisenhower, MacArthur, George Patton, Omar Bradley and Chester Nimitz. But it can also inspire younger readers to embark on the life of service that Marshall himself exemplified so thoroughly.