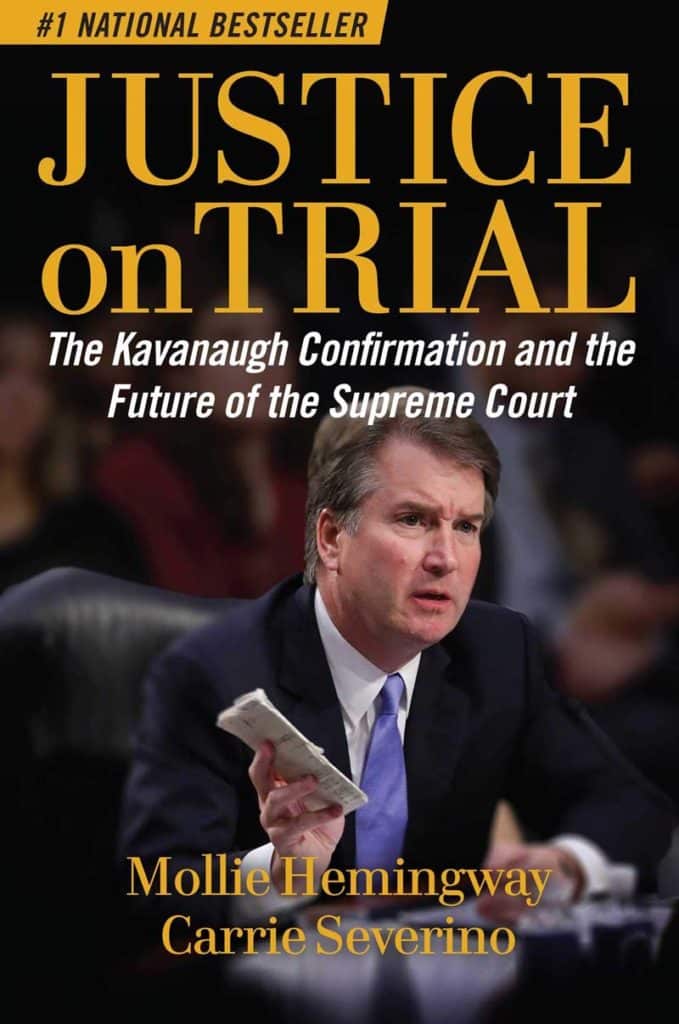

Justice on Trial: The Kavanaugh Confirmation and the Future of the Supreme Court, cowritten by Mollie Hemingway and Carrie Severino, might be retitled The [Ongoing] Education of Conservatives. Supreme Court nomination fights have become ground zero in the culture wars. In 1987, when President Reagan nominated Robert H. Bork for the court, Democrats were loaded for bear. The Reagan White House, then run by former senator Howard Baker, was asleep at the switch. When the opposition ran television ads opposing Bork featuring Gregory Peck of To Kill A Mockingbird fame, both Clint Eastwood and Charlton Heston volunteered to appear in a pro-Bork ad. The White House, incredibly enough, turned them down. One suspects Baker had no stomach for the fight with his old Democratic Party pals.

That nomination fight was the most important political event of the 1980s. Bork’s defeat allowed liberals to dominate the courts for the next 30-odd years, upholding rulings on abortion and affirmative action, while legalizing same sex marriage. In 1991, there was a replay with the Clarence Thomas nomination. By the time Kavanaugh was nominated, conservatives were in their battle stations. They now had a network (Fox News), plus numerous special interest groups able to spend millions on pro-Kavanaugh ads. It didn’t hurt that Kavanaugh had no intention of stepping down and even if he did, President Donald Trump would not have allowed it.

The nomination wars didn’t start with Bork. The co-authors don’t remember the 1969 donnybrook over Clement Haynsworth, a South Carolina jurist nominated by President Nixon. That was just as nasty. That fight broke down on regional, rather than on party lines. Southern Democrats such as Ernest Hollings (D–SC) and Richard Russell (D–GA) supported Haynsworth, while such liberal Republicans as Hugh Scott (R–PA) opposed him, prevailing in the end. (Today’s conservatives would never want to be on the same side as Russell or, say, Senator James Eastland (D–MS), who also supported Haynsworth.) This oversight hampers an otherwise intense read.

The nomination wars didn’t start with Bork. The co-authors don’t remember the 1969 donnybrook over Clement Haynsworth, a South Carolina jurist nominated by President Nixon. That was just as nasty. That fight broke down on regional, rather than on party lines. Southern Democrats such as Ernest Hollings (D–SC) and Richard Russell (D–GA) supported Haynsworth, while such liberal Republicans as Hugh Scott (R–PA) opposed him, prevailing in the end. (Today’s conservatives would never want to be on the same side as Russell or, say, Senator James Eastland (D–MS), who also supported Haynsworth.) This oversight hampers an otherwise intense read.

The co-authors are not sanguine about the future. The next time a Republican president nominates a jurist to the court, fireworks on a scale no one can possibly imagine will explode. The co-authors–and their fellow conservatives–are stuck with placing their hopes on the American people.

One justice who escaped the confirmation wars is Neil Gorsuch. The man can spend the rest of his days on the nation’s highest court, writing opinions to his heart’s content. A Republic If You Can Keep It is a compilation of Gorsuch’s opinions, speeches and testimony from recent years. The purpose of the collection is to show Gorsuch in a good light, a thoroughly harmless fellow. Kavanaugh is being raked over the coals on a regular basis. That won’t happen to Gorsuch. His collection is similar to George Will’s recent book, The Conservative Sensibility. You’d think the two compared notes. Gorsuch hits all the right notes: No to Plessy vs. Ferguson, yes to Brown vs. Board of Education and conveniently enough, no mention of Roe vs. Wade or Obergefell vs. Hodges.

Gorsuch does reject the notion of a “living” constitution. Plus, he maintains that the courts should rule on what a law is rather than what it should be. Alas, the volume is sunk by cliches. “The United States does not have a shared common culture in the classic sense,” the justice proclaims. “We do not have the many centuries of shared heritage that exists in, say, China or England.”

This statement is demonstratively false. The original colonies had a shared common culture (Anglo-Saxon-Celtic Protestant) for 167 years (1607 to 1776) before the American founding and a good 211 years (1776 to 1987) afterwards. That’s 380 years, nearly four centuries. A nation that lacks a common culture becomes…well, the kind of country America has become today. Only the character of a people can uphold a legal document such as the U.S. Constitution.