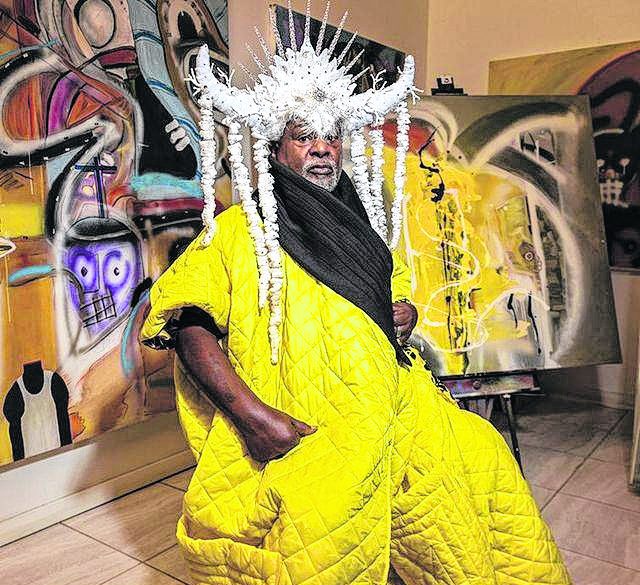

George Clinton owns the moniker “The Godfather of Funk,” but how did it all start for him and for the musicians who became the Parliament Funkadelic?

Clinton grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey, in the ’50s and ’60s where he was part owner of the Silk Palace barbershop, staffed by local musicians and singers. That’s where he formed the doo-wop group The Parliaments. During the ’60s, Clinton was a songwriter for Motown where he arranged and produced singles on many Detroit soul music labels. By the 1970s, Clinton had formed his other band, Funkadelic, comprised of some musicians from The Parliaments. Inspired by Jimi Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone and Frank Zappa, Clinton and his bands revolutionized R&B during the ’70s by creating a unique sound, and P-Funk was born.

Clinton and 15-member Parliament-Funkadelic were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997 and in 2019, they were given Grammy Lifetime Achievement Awards. On Jan. 19, 2024, Clinton received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In 2022, Clinton appeared as Gopher on The Masked Singer, but his appearance was quickly guessed by Robin Thicke who said, “When you are an original … nothing else feels and sounds like it.”

Clinton is a man who never slows down, having two albums in the works and heading out on tour with Parliament Funkadelic, who has been killing it with members of his musical family, their friends and him as bandleader.

His final message to all attending his concerts, including his stop at The Paramount in Huntington on May 25 is, “When you come to the show, bring two booties, one just isn’t enough!”

How did you go from owning a barbershop to being the Godfather of Funk?

While I was at the barbershop, I was writing songs like in ’59-’60s in the Brill Building in New York for a company that was owned by Detroit’s Motown Records. So, from that barbershop I would go back and forth to New York to do demos, write and record. We got our first hit record in ’67. We were part of that whole Motown thing, the R&B of it being with Motown artists and the pop side of it took us on tour with groups like Iggy Pop and MC5.

How would you describe the funk sound to a novice?

Funk basically is the DNA of a lot of sounds. You can have funk that is jazzy, gospel, or rhythm and blues, even funky rock ‘n’ roll. It’s the basis for a lot of dance music. The Beatles had a lot of funky stuff that they recorded. It sounded like folk music but it was very funky. If you give a song like “Eleanor Rigby” to Ray Charles to sing, you’ll see how much funk is in it. Beatles songs are conducive to funk. Funk is in a lot of music.

How does it feel to know you have elevated funk music to the recognition and acceptance it now has as a musical genre?

I feel proud of that because it was intentional. I was raised in the ’50s when rock ’n’ roll first started and I saw how rock ‘n’ roll came through part of the hood and went on to be the pop music of the world. It was no longer rock but pop. You heard it on pop radio and it was hard to get in there so we started out as Parliament and then we went into Funkadelic which was psychedelic like what Jimi Hendrix was doing and we got accepted into that rock thing over the years. It took us a long time. Maggot Brain is now like a rock stable. We didn’t want to let funk fade, so we stayed with the name and when it went out of style, we kept playing it, promoting it, and pointing out that whatever was coming out would still have funk in it. For instance, we kept funk part of hip-hop which is keeping the genre alive.

What do you hope your personal legacy will be?

Not only that we kept funk alive but right now we’re fighting for all the copyrights, ownerships and the generation of wealth from the music. We’re hoping to bring that to light and we want to get the masters back. Kind of like what Prince and Taylor Swift did. I’ve been fighting to get the masters back for the last 25 year. Not only for me, but for all the members of the band.

What do you see as the greatest challenges in the music industry from when you started as compared to now?

Going digital, that’s the biggest challenge for anybody that’s survived. Being able to deal with all the changes that have taken place from when we started. It was direct-to-disc in the beginning. Then to go through all that tape and all the different ways of recording. All of that was a challenge for a lot of musicians. I had fun watching the change from what I loved most, doo-wop into rock ‘n’ roll then rock, then psychedelic, then funk and then hip-hop. I had fun every time music started to change so I wasn’t averse to it. Then there’s the sociality of it, the financial thing of it, everything that goes along with trying to get a record out and getting paid for it. Congress is getting into it now to make laws that protect the people making music. Before it was just a hustle.

In 2018 you announced your retirement but you’re back on the road again. Why did you change your mind?

I tried it but there was nothing to do. All I needed was a little rest and once I got the rest, I started painting and doing art. And then I had to intellectualize that, it’s the same as writing songs so I found myself explaining in the art all the stuff I had done musically which got me clamoring for the music again. I was off during the pandemic and as soon as that was over I didn’t quite finish my retirement tour, so I’m back on tour for the third year. Now I’ve got no desire to stop.

What do all the awards that you have received mean to you?

It means more than I would have thought years ago when I was rocking, rolling, and reveling. When you play hard the awards don’t mean anything. But when you get to be 83 years old and you run into people that you were working in the same companies with in the ’60s, it makes you feel really good. Even getting a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. I walked up and down those streets a thousand times and suddenly my name is there! And of course, the Mothership being in the Smithsonian. That’s all really good! But since I’m still out here on the road having fun doing it, I try not to look at that stuff because it tends to make you want to be satisfied with what you’ve done and I don’t want to ever be satisfied. I like to keep on chasing it like nothing has ever happened.