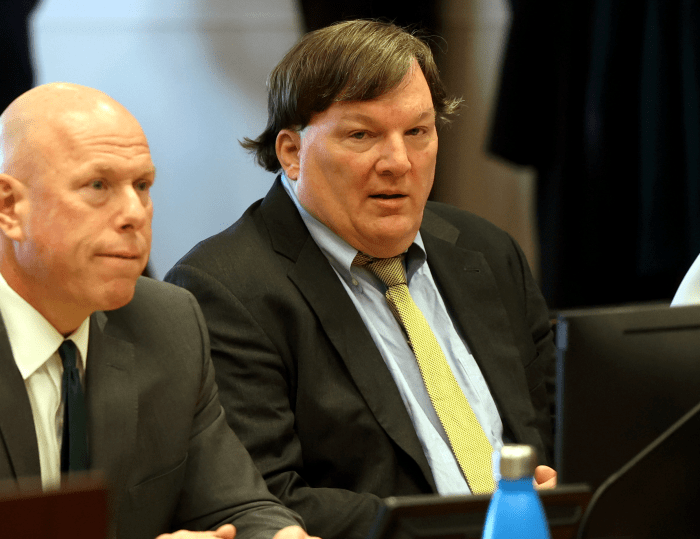

The defense team for Rex Heuermann, the alleged Long Island serial killer, called their first expert witness to the stand on June 17 in an ongoing pre-trial hearing — but the witness’s qualifications raised eyebrows across the courtroom, including those of Suffolk County Judge Timothy Mazzei.

The Frye hearing to determine the court admissibility of DNA evidence — which prosecutors say links Heuermann to six of the seven murders he is charged with — resumed as the defense called Nathaniel Adams, a systems engineer at consulting firm Forensic BioInformatics, Inc., to the stand as their first expert witness.

Defense attorney Danielle Coysh, perhaps in anticipation of the prosecution’s cross-examination, got the obvious out of the way first: the highest degree Adams has obtained is a Bachelor’s degree. He is currently in pursuit of his Master’s degree in Computer Science from Wright State University and has completed all his coursework, but has yet to complete his Master’s Thesis.

But upon cross-examination from District Attorney Ray Tierney, Adams, 38, admitted that it took him 10 years to finish his Associate’s degree from Sinclair College — a community college in Ohio, where he started taking courses around 2000 when he was in high school — and another three years to complete his Bachelor’s after transferring to Wright State University. He has been pursuing his Master’s degree for another 11 years.

“Can I interrupt for a second?” asked Mazzei. He had only spoken once since the hearing began four hours earlier to quip about a spelling mistake in Adams’ PowerPoint presentation. He turned to face Adams directly.

“You graduated high school when?”

2004, Adams said.

“And you graduated college when?”

Adams repeated that he graduated with his Bachelor’s degree in 2014.

“What were you doing in between?”

Adams hesitated. “I worked a variety of jobs,” he eventually said.

Mazzei looked bewildered but turned away from Adams and allowed the hearing to continue.

Tierney’s questioning also revealed that Adams, when he took the stand for a different case in 2016, testified that he hoped to graduate by the end of the year. Adams affirmed that that was his hope at the time, but he “lacked the confidence to formalize [his] thesis.” Tierney pointed out that that was eight or nine years ago.

The line of questioning turned to Adams’ colleagues and his thesis itself, of which he said has around 20 pages completed. Adams has taken longer to complete his Master’s than Wright State typically allows, and required an exemption approved by his academic superiors. Tierney’s questioning was seemingly leading up to establishing a conflict of interest if Dr. Dan Krane, who is also Adams’ boss at Forensic BioInformatics, was involved in the approval of said exemption.

Adams testified that his thesis advisor is Dr. Travis Doom, not Dr. Krane. Tierney implied that, while testifying in past cases, Adams had referred to Dr. Krane as an advisor for his thesis.

“They’re both involved,” Adams said.

“Didn’t you just testify three seconds ago that Dr. Doom is your thesis advisor?” Tierney asked.

Mazzei hid a smile behind his hands.

This was not the first time Dr. Krane had come up in the Frye hearing. When Dr. Richard Green of Astrea Labs, which tested the debated DNA sample in the Long Island serial killer case, took the stand as one of the prosecution’s expert witnesses during the April 17 court proceedings, Hueurmann’s lead defense attorney Michael Brown brought up a paper by Krane that criticized Astrea’s methods.

That paper, however, didn’t use data from humans; used too-small parameters; used an entirely different software from Astrea’s methods; and didn’t calculate the likelihood ratio of a match the same way as Astrea, said Green, some derision occasionally creeping into his voice. In addition, rather than being published in a reputable scientific journal, the paper was self-published “on the internet without the scrutiny of peer review,” Green said.

Forensic BioInformatics works closely with legal defense teams that are combating DNA evidence in court. Adams, who has worked at Forensic BioInformatics since 2012, has testified in court as an expert witness 30 times. He testified for the defense in each one, including the Idaho v Darymple case, which ultimately ruled Astrea’s DNA analysis to be court admissible.

Adams raised serious concerns about IBDGem, the software that Astrea developed and uses to analyze DNA samples. IBDGem has undergone 65 minor fixes since June 2020, when Astrea analyzed the DNA sample for the Long Island serial killer case, and 15 minor fixes since March 2023, when the scientific paper on IBDGem was published. The software has also gone through four releases — meaning new versions of it implemented — also since March 2023.

In other words, the version of IBDGem that tested the DNA allegedly belonging to Heuermann likely had defects that had to be corrected with bug fixes and updated versions of the software.

Also, when developing software, Adams said, one must adhere to the principles of validation and verification — meaning that the software’s goals must be objective and quantifiable, and its developer should be able to use those measures to prove that the software solves the problem it was created to solve. Without that validation and verification framework, it can be difficult for a software engineer to identify defects or failures until more serious consequences manifest later on in the development process.

IBDGem did not follow or implement an architecture of validation and verification, according to Adams, and “appears to have no quality assurance framework.”

“It’s unreliable,” he said.

IBDGem’s purpose is to create likelihood ratios, which essentially means to calculate the likelihood that a DNA sample is a match or not. But because the calculated likelihood ratio is “highly dependent on the data and software” of IBDGem, Adams said, it’s “difficult or practically impossible” to determine what the likelihood ratio should be, and whether IBDGem arrived at that matching conclusion.

Adams also raised concerns that IBDGem produces less accurate readings when processing a mixed sample, which is a sample that includes DNA from multiple individuals. Tierney noted the DNA sample in the Long Island serial killer case was extracted from a strand of hair, seemingly pointing to a mixed sample being unlikely.

In April 16 court proceedings, Dr. Green testified that in the 3,920 control tests that Astrea ran on IBDGem — meaning tests where the scientists already knew whether the sample was a match or not and wanted to see if IBDGem arrived at that same conclusion — the software’s likelihood ratio was always correct. It never concluded that a known match was not a match, or that a known mismatch was a match. He also testified that, in the additional thousands of tests where Astrea intentionally simulated errors like mixed samples, IBDGem still never incorrectly identified a sample as a match when it was a mismatch.

“The more error (DNA contamination or mixing) we introduce, the less positive” the likelihood of a match calculated by IBDGem, Green said. That is to say, introducing a mixed sample does not lead IBDGem to indicate a match where there is not one.

“If anything,” Green said, the software is more likely to produce “a false negative.”

The hearing is scheduled to proceed on June 18.