POLAR OPPOSITES

Katherine Rainone, a 24-year-old Manhasset native and environmental activist, was a member of the group of 14 other American youth delegates who seized a rare moment when the whole world was watching.

Just as U.S. delegate Todd Stern was about to make a statement Dec. 8, a member of the group, 21-year-old Abigail Borah of New Jersey, shouted from the back row that, among other things, “2020 is too late to wait!”

She was referring to the year the new climate accord would take effect—if the 194 parties who agreed to continue talks reach an agreement and stick to it. It’s also the year after which a recent UN report suggested would be the point of no return if carbon emissions continue to rising.

“It was the most wonderfully orchestrated stunt that I think I’ve ever been a part of,” Rainone says of the disruption, which has been posted on YouTube. “He had gone into a press conference about an hour later and was completely fumbling.”

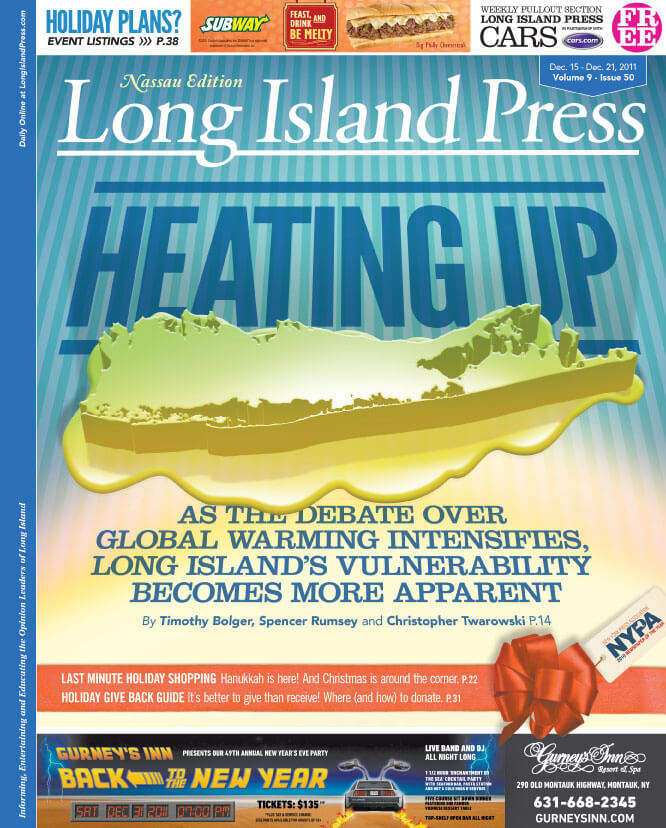

Global warming is “not fake, it’s real,” she says. “It’s scientifically proven, and it’s a real issue that can potentially affect those on Long Island if this continues.”

Not everyone, however—namely some members of the U.S. Congress—believes in the urgency of the problem or the success of Durban.

As Noam Chomsky, esteemed MIT linguistics professor and left-wing analyst, recently wrote in In These Times, American attitudes toward global warming and climate change lag behind the rest of the world, and one reason is that “In 2009 the energy industries, backed by business lobbies, launched major campaigns that cast doubt on the near-unanimous consensus of scientists on the severity of the threat of human-induced global warming. The consensus is only ‘near-unanimous’ because it doesn’t include the many experts who feel that climate-change warnings don’t go far enough, and the marginal group that deny the threat’s validity altogether. The standard ‘he says/she says’ coverage of the issue keeps to what is called ‘balance’: the overwhelming majority of scientists on one side, the denialists on the other…. One effect is that scarcely one-third of the U.S. population believes that there is a scientific consensus on the threat of global warming—far less than the global average, and radically inconsistent with the facts.”

According to an international survey conducted by the Program on International Policy Attitudes, a research project based at the University of Maryland, “In general, the United States has been most widely seen as the country having the most negative effect on the world’s environment, followed by China.”

Under the new accord, set to take effect by 2020, all countries will have to follow the same rules.

“Durban’s real accomplishment was to keep the slow, torturous process of climate negotiations alive—with the biggest carbon emitters now involved,” Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson wrote recently. “This buys time for real solutions to emerge.”

Neal Lewis, executive director of Molloy College’s Sustainability Institute in Rockville Centre, says he’s optimistic about what happened at the Durban conference.

“There is this glimmer of hope that for the first time we may have broken through the question of [whether] everybody has to be in on the solution,” Lewis says. “We all have to be in on it.”

He also sees parallels to what’s going on here.

“I do think what we see playing out internationally in these efforts with the treaty is very similar to what plays out in Washington and Albany,” Lewis says. “We do see a similar dynamic where it’s very tough to stand up to powerful corporations and powerful interests.”

But he believes that making energy use more efficient and increasing the use of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, will prove more economical in the long run and benefit areas like Long Island that could face the full impact of rising sea levels due to greenhouse gas consumption.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is tasked with protecting the coastline, among its other priorities.

Joseph Vietri, director of the corps’ national planning center for coastal and storm damage, says that the corps now considers three scenarios in its planning ranging from one foot to three feet (a meter), which only makes the problem more complicated to solve.

“Clearly the evidence, I think, is irrefutable that we are going to experience an increase,” Vietri says. “The question is: will it be as much as a meter? And if so then we’ve got some very, very serious problems.”

Some in Congress agree, but not all.